In my recent post on the current hearings at the Old Bailey over Julian Assange’s extradition to the United States, where he would almost certainly be locked away for the rest of his life for the crime of doing journalism, I made two main criticisms of the Guardian.

A decade ago, remember, the newspaper worked closely in collaboration with Assange and Wikileaks to publish the Iraq and Afghan war diaries, which are now the grounds on which the U.S. is basing its case to lock Assange behind bars in a super-max jail.

My first criticism was that the paper had barely bothered to cover the hearing, even though it is the most concerted attack on press freedom in living memory. That position is unconscionably irresponsible, given its own role in publishing the war diaries. But sadly it is not inexplicable. In fact, it is all too easily explained by my second criticism.

A journalist due to testify at Julian Assange's extradition hearing makes a very pertinent point. This is the biggest attack on press freedom in our lifetimes. Why are UK editors not demanding to be heard at the Old Bailey? Where are they? Where is the Guardian? https://t.co/fFRFvGpYdi

— Jonathan Cook (@Jonathan_K_Cook) September 8, 2020

That criticism was chiefly levelled at two leading journalists at the Guardian, former investigations editor David Leigh and reporter Luke Harding, who together wrote a book in 2011 that was the earliest example of what would rapidly become a genre among a section of the liberal media elite, most especially at the Guardian, of vilifying Assange.

In my earlier post I set out Leigh and Harding’s well-known animosity towards Assange–the reason why one senior investigative journalist, Nicky Hager, told the Old Bailey courtroom the pair’s 2011 book was “not a reliable source”. That was, in part, because Assange had refused to let them write his official biography, a likely big moneymaker. The hostility had intensified and grown mutual when Assange discovered that behind his back they were writing an unauthorised biography while working alongside him.

But the bad blood extended more generally to the Guardian, which, like Leigh and Harding, repeatedly betrayed confidences and manoeuvred against Wikileaks rather than cooperating with it. Assange was particularly incensed to discover that the paper had broken the terms of its written contract with Wikileaks by secretly sharing confidential documents with outsiders, including the New York Times.

When lawyers for the US yet again quote from a book by the Guardian's David Leigh in a desperate bid to bolster their flimsy case against Julian Assange, investigative journalist Nicky Hager replies: 'I would not regard that [book] as a reliable source' https://t.co/uPk8wVX5RF

— Jonathan Cook (@Jonathan_K_Cook) September 20, 2020

Leigh and Harding’s book now lies at the heart of the U.S. case for Assange’s extradition to the U.S. on so-called “espionage” charges. The charges are based on Wikileaks’ publication of leaks provided by Chelsea Manning, then an army private, that revealed systematic war crimes committed by the U.S. military.

Inversion of truth

Lawyers for the U.S. have mined from the Guardian book claims by Leigh that Assange was recklessly indifferent to the safety of U.S. informants named in leaked files published by Wikileaks.

Assange’s defence team have produced a raft of renowned journalists, and others who worked with Wikileaks, to counter Leigh’s claim and argue that this is actually an inversion of the truth. Assange was meticulous about redacting names in the documents. It was they–the journalists, including Leigh–who were pressuring Assange to publish without taking full precautions.

Prof Sloboda, of Iraq Body Count, joins others in offering first-hand evidence that Assange was scrupulous in redacting names. He 'resisted pressure from media partners [Guardian?] to speed up the process. Assange always meticulously insisted on redaction' https://t.co/vD2TqDVmlD

— Jonathan Cook (@Jonathan_K_Cook) September 18, 2020

Of course, none of these corporate journalists–only Assange–is being put on trial, revealing clearly that this is a political trial to silence Assange and disable Wikileaks.

But to bolster its feeble claim against Assange–that he was reckless about redactions–the U.S. has hoped to demonstrate that in September 2011, long after publication of the Iraq and Afghan diaries, Wikileaks did indeed release a trove of documents–official U.S. cables–that Assange failed to redact.

This is true. But it only harms Assange’s defence if the U.S. can successfully play a game of misdirection–and the Guardian has been crucial to that strategy’s success. Until now the U.S. has locked the paper into collaborating in its war on Assange and journalism–if only through its silence–by effectively blackmailing the Guardian with a dark, profoundly embarrassing secret the paper would prefer was not exposed.

In fact, the story behind the September 2011 release by Wikileaks of those unredacted documents is entirely different from the story the court and public is being told. The Guardian has conspired in keeping quiet about the real version of events for one simple reason–because it, the Guardian, was the cause of that release.

Betrayal of Assange and journalism

Things have got substantially harder for the paper during the extradition proceedings, however, as its role has come under increasing scrutiny–both inside and outside the courtroom. Now the Guardian has been flushed out, goaded into publishing a statement in response to the criticisms.

It has finally broken its silence but has done so not to clarify what happened nine years ago. Rather it has deepened the deception and steeped the paper even further in betrayal both of Assange and of press freedom.

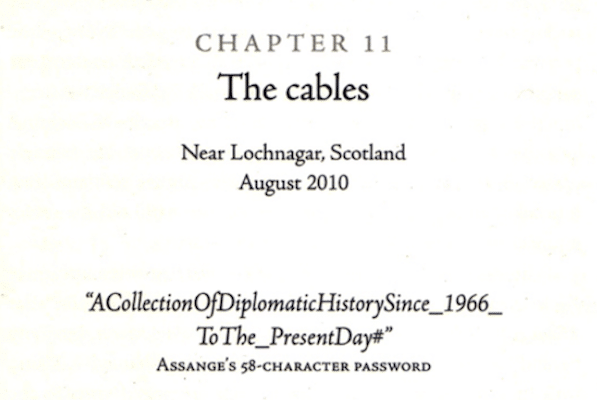

The February 2011 Guardian book the U.S. keeps citing contained something in addition to the highly contentious and disputed claim from Leigh that Assange had a reckless attitude to redacting names. The book also disclosed a password–one Assange had given to Leigh on strict conditions it be kept secret–to the file containing the 250,000 encrypted cables. The Guardian book let the cat out of the bag. Once it gave away Assange’s password, the Old Bailey hearings have heard, there was no going back.

Assange's lawyers are noting the long-known fact that Guardian journalists made the unredacted cables accessible through incompetence – they published the file's password. The point is: If anyone should be in the dock (and no one should be!), it would be the Guardian, not Assange https://t.co/4fQlUEXLTP

— Jonathan Cook (@Jonathan_K_Cook) February 25, 2020

Any security service in the world could now unlock the file containing the cables. And as they homed in on where the file was hidden at the end of the summer, Assange was forced into a desperate damage limitation operation. In September 2011 he published the unredacted cables so that anyone named in them would have advance warning and could go into hiding–before any hostile security services came looking for them.

Yes, Assange published the cables unredacted but he did so–was forced to do so–by the unforgivable actions of Leigh and the Guardian.

But before we examine the paper’s deceitful statement of denial, we need to interject two further points.

First, it is important to remember that claims of the damage this all caused were intentionally and grossly inflated by the U.S. to create a pretext to vilify Assange and later to justify his extradition and jailing. In fact, there is no evidence that any informant was ever harmed as a result of Wikileaks’ publications–something that was even admitted by a U.S. official at Manning’s trial. If someone had been hurt or killed, you can be sure that the U.S. would be clamouring about it at the Old Bailey hearings and offering details to the media.

Second, the editor of a U.S. website, Cryptome, pointed out this week at the hearings that he had published the unredacted cables a day before Wikileaks did. He noted that U.S. law enforcement agencies had shown zero interest in his publication of the file and had never asked him to take it down. The lack of concern makes explicit what was always implicit: the issue was never really about the files, redacted or not; it was always about finding a way to silence Assange and disable Wikileaks.

Cryptome and another website published unredacted cables, and only after this did @WikiLeaks republish the already published documents. The US prosecution is trying to confuse the chain of events. pic.twitter.com/zmjVMui8Ev

— Don't Extradite Assange (@DEAcampaign) September 21, 2020

The Guardian’s deceptions

Every time the U.S. cites Leigh and Harding’s book, it effectively recruits the Guardian against Assange and against freedom of the press. Hanging over the paper is effectively a threat that–should it not play ball with the U.S. campaign to lock Assange away for life–the U.S. could either embarrass it by publicly divulging its role or target the paper for treatment similar to that suffered by Assange.

And quite astoundingly, given the stakes for Assange and for journalism, the Guardian has been playing ball–by keeping quiet. Until this week, at least.

Under pressure, the Guardian finally published on Friday a short, sketchy and highly simplistic account of the past week’s hearings, and then used it as an opportunity to respond to the growing criticism of its role in publishing the password in the Leigh and Harding book.

The Guardian’s statement in its report of the extradition hearings is not only duplicitous in the extreme but sells Assange down the river by evading responsibility for publishing the password. It thereby leaves him even more vulnerable to the U.S. campaign to lock him up.

Let’s highlight the deceptions:

1. The claim that the password was “temporary” is just that–a self-exculpatory claim by David Leigh. There is no evidence to back it up beyond Leigh’s statement that Assange said it. And the idea that Assange would say it defies all reason. Leigh himself states in the book that he had to bully Assange into letting him have the password precisely because Assange was worried that a tech neophyte like Leigh might do something foolish or reckless. Assange needed a great deal of persuading before he agreed. The idea that he was so concerned about the security of a password that was to have a life-span shorter than a mayfly is simply not credible.

It is strictly false that the Guardian was told the password or file were temporary, hence the elaborate password handover method.

— WikiLeaks (@wikileaks) September 1, 2011

2. Not only was the password not temporary, but it was based very obviously on a complex formula Assange used for all Wikileaks’ passwords to make them impossible for others to crack but easier for him to remember. By divulging the password, Leigh gave away Assange’s formula and offered every security service in the world the key to unlocking other encrypted files. The claim that Assange had suggested to Leigh that keeping the password secret was not of the most vital importance is again simply not credible.

3. But whether or not Leigh thought the password was temporary is beside the point. Leigh, as an experienced investigative journalist and one who had little understanding of the tech world, had a responsibility to check with Assange that it was okay to publish the password. Doing anything else was beyond reckless. This was a world Leigh knew absolutely nothing about, after all.

But there was a reason Leigh did not check with Assange: he and Harding wrote the book behind Assange’s back. Leigh had intentionally cut Assange out of the writing and publication process so that he and the Guardian could cash in on the Wikileak founder’s early fame. Not checking with Assange was the whole point of the exercise.

4. It is wrong to lay all the blame on Leigh, however. This was a Guardian project. I worked at the paper for years. Before any article is published, it is scrutinised by backbench editors, sub-editors, revise editors, page editors and, if necessary, lawyers and one of the chief editors. A Guardian book on the most contentious, incendiary publication of a secret cache of documents since the Pentagon Papers should have gone through at least the same level of scrutiny, if not more.

So how did no one in this chain of supervision pause to wonder whether it made sense to publish a password to a Wikileaks file of encrypted documents? The answer is that the Guardian was in a publishing race to get its account of the ground-shattering release of the Iraq and Afghan diaries out before any of its rivals, including the New York Times and Der Spiegel. It wanted to take as much glory as possible for itself in the hope of winning a Pulitzer. And it wanted to settle scores with Assange before his version of events was given an airing in either the New York Times or Der Spiegel books. Vanity and greed drove the Guardian’s decision to cut corners, even if it meant endangering lives.

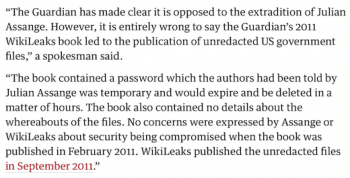

5. Nauseatingly, however, the Guardian not only seeks to blame Assange for its own mistake but tells a glaring lie about the circumstances. Its statement says: “No concerns were expressed by Assange or WikiLeaks about security being compromised when the book was published in February 2011. WikiLeaks published the unredacted files in September 2011.”

It is simply not true that Assange and Wikileaks expressed no concern. They expressed a great deal of concern in private. But they did not do so publicly–and for very good reason.

Computer expert at Assange hearing calls the Guardian's David Leigh 'a bad faith actor' over his publishing a Wikileaks password that opened the door to every security service in the world being able to access 250,000 encrypted cables https://t.co/QLJj1McNrJ

— Jonathan Cook (@Jonathan_K_Cook) September 22, 2020

Any public upbraiding of the Guardian for its horrendous error would have drawn attention to the fact that the password could be easily located in Leigh’s book. By this stage, there was no way to change the password or delete the file, as has been explained to the Old Bailey hearing by a computer professor, Christian Grothoff, of Bern University. He has called Leigh a “bad faith actor”.

So Assange was forced to limit the damage quietly, behind the scenes, before word of the password’s publication got out and the file was located. Ultimately, six months later, when the clues became too numerous to go unnoticed, and Cryptome had published the unredacted file on its website, Assange had no choice but to follow suit.

This is the real story, the one the Guardian dare not tell. Despite the best efforts of the U.S. lawyers and the judge at the Old Bailey hearings, the truth is finally starting to emerge. Now it is up to us to make sure the Guardian is not allowed to continue colluding in this crime against Assange and the press freedoms he represents.