More than two decades after the dictatorship of Suharto‘s New Order was toppled down in 1998, Indonesia is still controlled by an oligarchy and virtually the same old elites linked to Suharto era. Despite widespread criticism, the country’s National Armed Forces as well as National Police continue to play an expanded role in civilian life.

Notably, the militarisation and re-militarisation in Indonesian politics, and a greater role of military and police in both executive and legislative, have occurred even in the period of current president Joko Widodo (popularly known as Jokowi) who, despite being a civilian, is publicly mocked for following the path of the late military dictator Suharto.

Jokowi worked hard during his first two years in power to build political support with a coalition in the government and the House of Representatives, which is made up of the old oligarchy. He was aware he needed political supports from various political factions. But the result is that the oligarchy, the old elites, the military and ex-military forces still remain dominant in Indonesian politics, risking a setback to the Suharto era, where military circles virtually controlled every strategic political decision.

The current political situation

When entering national politics in 2014, Jokowi was a new face on Indonesia’s political scene who was believed to have no connection with the past political sins of the dictatorship era. During his presidential election campaign against his rival candidate, former military general Prabowo Subianto (the first in 2014 and the second in 2019), Jokowi promised to settle the serious human rights violations in the past. With this promise, he unsurprisingly gained more support than his opponent–especially in 2014 since he faced Prabowo who, among others, was responsible for past human rights violations.

Nonetheless, over six years in power (the first term in 2014-2019 and the second in 2019-2024), Jokowi has not done anything to keep his promises. There are at least six major human rights violations that remain unsettled, including the 1965 communist purge, various kidnappings and unresolved shootings in the 1980s, the May 1998 riots and the disappearances of activists. To make matters worse, Jokowi’s administration has also overseen numerous human right violations by the military and police perpetuated in places such as Papua. Cases of violence committed by military has continued to increase from year to year. Instead of addressing this, Jokowi focussed on economic development through infrastructure projects.

Over the past years, Indonesia’s GDP has indeed grown steadily and the country is slowly establishing itself as one of the world’s most important economic players. Under Jokowi, Indonesia produced various regulations to attract more foreign investment, including favourable tax conditions and other incentives for businesses.

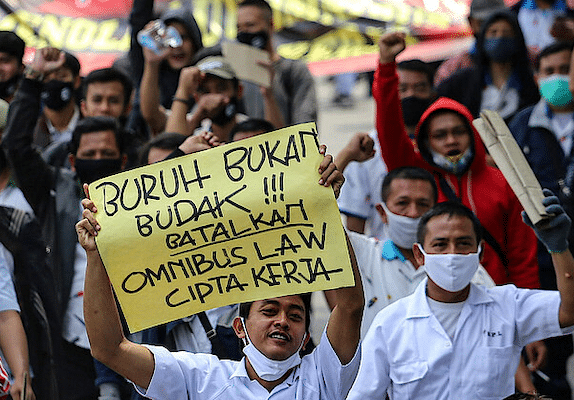

On the other hand, labour laws and minimum wage regulation were more and more flexiblised. For instance, since 2015, workers and trade unions are no longer able to negotiate minimum wages. Moreover, on 5 October 2020, Indonesia’s House of Representatives passed the Omnibus Law on Job Creation despite massive public protest. This could throw more momentum of Indonesia’s return to dictatorship as the police cracked down on the protesters, mostly students and young workers.

Omnibus Law controversies

The Omnibus Law is part of Jokowi’s ambition to attract more foreign investment. Like Suharto’s New Order in the past, Jokowi attempts to obliterate labour rights and strip away environmental protections. The Omnibus Law serves to privatise public goods and services such as electricity and education. The law will clearly have a devastating impact on families and households, as the provisions would cut wages, remove important sick leave provisions and other protections, and undermine job security. The International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) denounced that the ’sheer scale, complexity and contents of the law are a violation of Indonesia’s responsibilities under international human rights law’.

From the beginning, the Omnibus Law has drawn criticism by the general public, as a result of the lack of transparency on the part of the government in its drafting. In August 2020, the National Human Rights Commission has recommended that deliberations on the Omnibus Bill not be continued, in the framework of respecting, protecting and upholding human rights for all Indonesian people. Earlier, in March 2020, a number of civil society organizations were also urging the House and the government to cancel deliberations on the Bill, bearing in mind that in the midst of COVID-19 pandemic it would not be able to effectively deliberate the legislation.

In formulating the law, both government and the House of Representatives were reluctant to seriously consult, let alone accommodate, input from the public, especially those most affected by the law. The formulation and legislation of the Omnibus Law had taken place under a cloak of secrecy. Days after the passing of the law, the final draft was still not available to the public.

Worse still, as the Omnibus Law was passed in a rush, the bill could not be checked and discussed by the legislators themselves, leading to major procedural flaws. There are at least three versions of the law that have widely circulated, the first with 905 pages, the second with 1,035 pages and the third with 812 pages. Some changes were made even after its passing until the ‘final’ version (812 pages) was made available for public on 12 October.

On the other hand, a joint force of 9,332 policemen, soldiers and Public Order Agency officers had been deployed in Jakarta on the day following the legislation to enforce security and crack down on the protesters. The protest against the Omnibus Law also took place in many cities across 18 provinces. More than 5000 protesters were detained and accused of inciting the demonstration, many of whom were physically abused including several journalists covering the protest. This crackdown against peaceful protest has actually been a norm in Indonesia in the past years, though it was lauded as the new model of democracy in Southeast Asia and the third largest democracy in the world.

Economy first, anything else later

At the same time, the spread of COVID-19 in Indonesia has continued unabated. As of 18 October 2020, confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Indonesia have reached 361,867, 285,324 out of whom are recovered and 12,511 people died. The problem is that Indonesia has tested a smaller share of its population than every other major economy. It has conducted COVID-19 tests on eight out of every 1000 people, which remains far below the WHO standard.

While many countries have been able to flatten the curve including in the neighbouring countries in Southeast Asia, the number of COVID-19 transmissions in Indonesia is still rising. It has even expanded nationwide to malaria-endemic areas such as the provinces of East Nusa Tenggara, Maluku and Papua, posing a double burden on already disadvantaged people in the country’s eastern region.

From the very beginning, the Jokowi government has been criticised publicly for its poor response to the COVID-19 pandemic in the country. The government took two months to come up with a national policy strategy on how the government and citizenry should manage the epidemic. Social activists argue that the decision to impose a partial lockdown in April 2020 came so late because the government was trying to evade having to pay the greater economic costs of the lockdown–and showed itself unwilling to safeguard the majority of workers in the informal economy.

In such a situation, it would have been wise for the government to focus more on facing COVID-19 rather than legislating Omnibus Law without proper public consultation, in particular as the working population are the most affected and the hardest hit by the pandemic. What can we expect from Jokowi, if he pretends to run Indonesia democratically but follows the path of the dictator Suharto? Civil society groups in Indonesia, for one, have declared the Omnibus Law unconstitutional, fearing that Indonesia is officially returning to an authoritarian state.