Dear friends,

Greetings from the desk of the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

A decade has now slipped by since a man named Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire in the Tunisian town of Sidi Bouzid on 17 December 2010. Bouazizi, a street vendor, took this extreme step after policemen harassed him for trying to survive. Not long after, thousands of people in this small Tunisian town gathered in the street to express their anger. Their outburst spread to the capital city, Tunis, where trade unions, social organisations, political parties, and civic groups marched into the avenues to overthrow the government of Zine El Abidine Ben Ali. Demonstrations in Tunisia inspired similar outbreaks around the Mediterranean Sea from Egypt to Spain, the chant of Cairo’s Tahrir Square–ash-sha’b yurid isqat an-nizam ‘(the people want to overthrow the regime’)–redolent with the emotion of hundreds of millions.

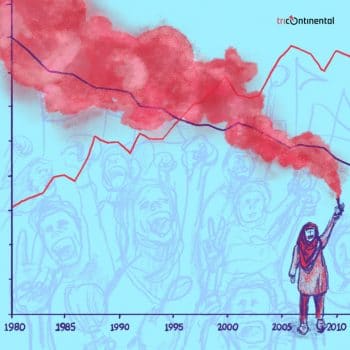

People poured into the streets, their sentiment captured by the Spanish term indignados: indignant, or outraged. They came to say that their hopes were being crushed by forces both visible and invisible. The billionaires of their own societies and their cosy relationship with the state–despite the global downturn spurred by the credit crisis of 2007-08–were easy to see. Meanwhile, the forces of finance capital that had eroded the capacity of their governments (if they were favourable to the people) to provide humane policies were much harder to see, but no less devastating in their consequences.

The sentiment that fuelled the slogan overthrow the regime was shared widely by large majorities of people who had become dulled by the futility of voting for evils and lesser evils; these people were now seeking something beyond the horizon of the election games which seemed to bring so little change. Politicians ran for elections saying one thing, and then did the exact opposite when they took charge.

In the United Kingdom, for instance, the student protests that broke out in November-December 2010 were against the betrayal by the Liberal Democrats of their pledge not to raise fees; regardless of who they voted for, the outcome was that the people suffered. Greece, France: now here too!, chanted the students in the UK. They could have added Chile, where the students (known as los pingüinos, or ‘the penguins’) took to the streets against the education cuts; their protests would pick up again in May 2011 and last almost two years in el invierno estudiantil chileno, the ‘Chilean Student Winter’. In September 2011, the Occupy Movement in the United States would join this wave of global outrage, emerging out of the gross failure of the U.S. government to address mass evictions spurred by the mortgage calamity that morphed into the credit crisis of 2007-08. ‘The only way to experience the American Dream’, someone wrote on the walls of Wall Street, ‘is while sleeping’.

Overthrow the regime was the slogan because faith in the establishment had weakened; more was demanded of life than what was on offer from the neoliberal governments and the central bankers. But the point of the protests was not simply to overthrow the government alone, since there was widespread recognition that this was not a problem of the governments: it was a deeper problem about the kind of political possibilities that remained open to human society. A generation or more had experienced austerity cuts by governments of different kinds, even social democratic governments that were told that the rights of the wealthy bondholders–for instance–were far more important than the rights of the totality of the citizens. It was bewilderment at the failure of what appeared to be progressive governments, such as the Syriza coalition in Greece later in 2015, to deliver on their basic promise of no more austerity that spurred this kind of attitude.

The uprising had a truly global character. A million people in Red Shirts in Bangkok on 14 March 2010 took to the streets against a state of the military, the monarchy, and the monied sections; in Spain, half a million indignados marched in the streets of Madrid on 15 October 2011. The Financial Times ran an influential article calling this ‘the year of global indignation’, with one of its leading commentators writing that the revolt pitted ‘an internationally-connected elite against ordinary citizens who feel excluded from the benefits of economic growth, and angered by corruption’.

A report by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) from October 2008 showed that between the 1980s and the 2000s, inequality rose in each of the twenty richest countries in the world who are members of the OECD. The situation in the developing world was catastrophic; a report by the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) from 2008 showed that the share of national consumption by the poorest fifth of the population in developing regions had declined from 4.6% to 3.9% between 1990 and 2004. This was gravest in Latin America, the Caribbean, and sub-Saharan Africa, where the poorest fifth accounted for merely 3% of national consumption or income. Whatever funds had been gathered to help the banks stave off a serious crisis in 2008 did not translate into any income redistribution for the billions of people who saw their lives become increasingly precarious. This was the major spur for the uprisings of that period.

It is important to point out that in all these statistics there was a hopeful sign. In March 2011, Alicia Bárcena, the head of the UN Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), wrote that despite the high levels of income inequality, poverty rates in the region had dropped due to the social policies of some of the governments in the region. Bárcena had in mind the social democratic governments such as in Brazil under President Lula da Silva, with schemes such as the Bolsa Familia, and left governments such as in Bolivia under President Evo Morales and Venezuela under President Hugo Chávez. The indignant in these parts of the world had entered government and were driving a different agenda for themselves.

How swiftly the wealthy turned from the language of ‘democracy promotion’ to the language of law and order, sending in the police and the F-16s to clear out public plazas and to threaten countries with bombardment and with coup d’états.

The Arab Spring, which drew its name from the 1848 revolts across Europe, quickly turned cold as the West encouraged a hot war between regional powers (Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey) with the epicentres in Libya and Syria. The destruction of the Libyan state by the 2011 NATO attack sidelined the African Union, suspended all talk of the Afrique as a currency to substitute for the French Franc and the U.S. Dollar, and drew in a massive French and U.S. military intervention along the Sahel region from Mali to Niger.

Immense pressure to overthrow the government in Syria began in 2011 and deepened in 2012. This fragmented Arab unity, which had been growing after the illegal U.S. war on Iraq in 2003; made Syria the frontline of a regional war between Iran and its adversaries (Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates); and diminished the centrality of the cause of the Palestinians. In Egypt, General Mohamed Ibrahim, the interior minister in a new government of generals, said coldly, ‘We are living a golden age of unity between the judges, the police, and the army’. The North Atlantic liberals rushed behind the generals; in December 2020, French president Emmanuel Macron honoured Egypt’s president–a former general–Abdel Fattah el-Sisi with the Légion d’honneur, France’s highest award.

In Latin America, meanwhile, Washington instigated a series of shenanigans to overthrow what was known as the Pink Tide. This ranged from the attempted coup against the Venezuelan government in 2002 to the 2009 coup in Honduras and the hybrid war prosecuted against every progressive government in the American hemisphere from Haiti down to Argentina. A decline in commodity prices–especially oil prices–spluttered economic activity in the hemisphere. Washington used this opportunity to exert information, financial, diplomatic, and military pressure on the left governments, many of which could not withstand the pressure. The coup against the government of Fernando Lugo of Paraguay in 2012 was a harbinger for what was to come against President Dilma of Brazil in 2016.

Every inch of hope to change the economic and political system was driven underfoot by war and coups and by immense pressure from organisations such as the IMF. Older language of ‘tax and subsidy reform’ and ‘labour market reform’ re-emerged to suffocate attempts by states to provide relief to the unemployed and the hungry. Long before the coronavirus, hope had become calcified and rottenness had become normal as migrants drowned in seas and sat in concentration camps while dead money slipped across borders to tax havens (offshore financial centres hold upwards of $36 trillion, an astronomical amount).

A glance backward to the uprisings of a decade ago requires that we pause at the door of the prisons in Egypt, where some of the young people who had been arrested for their hopefulness remain incarcerated. Two political prisoners, Alaa Abdel El-Fattah and Ahmed Douma shouted to each other between their cells, a conversation which was published as Graffiti for Two. What did they fight for? ‘We fought for a day, one day that would end without the suffocating certainty that tomorrow would replicate it as all days had been replicated before’. They sought an exit from the present; they sought a future. Revolutionaries, when they rise, Alaa and Ahmed wrote, care ‘for nothing but love’.

A glance backward to the uprisings of a decade ago requires that we pause at the door of the prisons in Egypt, where some of the young people who had been arrested for their hopefulness remain incarcerated. Two political prisoners, Alaa Abdel El-Fattah and Ahmed Douma shouted to each other between their cells, a conversation which was published as Graffiti for Two. What did they fight for? ‘We fought for a day, one day that would end without the suffocating certainty that tomorrow would replicate it as all days had been replicated before’. They sought an exit from the present; they sought a future. Revolutionaries, when they rise, Alaa and Ahmed wrote, care ‘for nothing but love’.

In their prison cells in Cairo, they hear stories of the Indian farmers, whose struggles have inspired a nation; they hear of the striking nurses from as far afield as Papua New Guinea and the United States; they hear of striking factory workers in Indonesia and South Korea; they hear that the betrayal of the Palestinians and the Saharawi people provoked street actions around the world. For a few months in 2010-2011, the ‘suffocating certainty’ that there is no future was set aside; a decade later, the people on the streets seek a future that is a break from the insufferable present.

Warmly,

Vijay.