This article was produced by Globetrotter.

On December 8, a Conviasa flight prepared to take off from Caracas, Venezuela, for Mexico City. It planned to carry 200 election observers and journalists who came to Venezuela from a range of countries to monitor the National Assembly elections that were held on December 6. The plane sat on the tarmac, luggage on board, with the passengers ready to board—at which point, the delay began. Hours went by. The airline had previously filed a flight plan, which included using Colombian airspace; now, hours before the flight was to take off, the government of Colombia denied the aircraft the right of transit (as established by the 1944 Chicago Convention, which Colombia joined in 1947). The plane took off eventually but had to land on the Colombian-Venezuelan border at Maracaibo to refuel. Tension ran through the aircraft (one of us, Vijay, was on that plane).

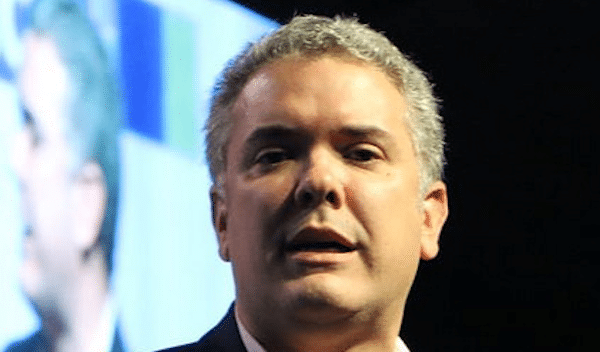

In Caracas, another one of us—Zoe—was at a press conference being given by President Nicolás Maduro about the National Assembly election result. Zoe asked President Maduro about the plane that was then on the ground at Maracaibo. “These are things that happen because of the sick obsession that Iván Duque has with Venezuela,” said Maduro of his Colombian counterpart, President Iván Duque. Duque, Maduro said, “hates Venezuela. … Iván Duque wants a war with Venezuela, but he has not been able to achieve it.” “Dozens of Colombian planes fly over Venezuela every day, and I am not going to personally, as a president, stop a plane,” Maduro said. “This goes to show how far his obsession goes. Do you see how dangerous it is?” Not long after Maduro made this statement, word came from Bogotá that the Conviasa flight could take off, and it—with Vijay on board—made its journey to Mexico City.

Dangers in Colombia

Iván Duque has made it his mission to paint Venezuela as an anti-democratic country. Not a day seems to go by without some statement from him about the situation in Venezuela. Maduro characterized this as a “fatal obsession.” Meanwhile, Maduro pointed out in the press conference, social movement leaders in Colombia have been kidnapped, disappeared, tortured, and assassinated.

A week after this press conference, the Institute of Development and Peace Studies (Indepaz) in Colombia released a report which showed that since 2016, at least 1,090 leaders of social movements have been assassinated; 695 of these assassinations, or 63 percent of them, have taken place during the presidency of Iván Duque, who took office in August 2018. In 2020, there have been 85 massacres, the bulk of them in the provinces of Antioquia, Cauca, and Nariño.

On December 15 and 16, the Colombian authorities arrested three leaders of the peasant organization Coordinador Nacional Agrario and the Congreso de los Pueblos (People’s Congress)—Adelso Gallo, Teófilo Acuña, and Robert Daza. They were charged with “aggravated rebellion”; this is a specific charge that refers to the use of arms to overthrow the government and the constitutional regime, and which carries a very heavy sentence. There is no evidence that Gallo, Acuña, or Daza was preparing any such rebellion.

Acuña is the very opposite of an armed militant, since he is a spokesperson for the Dialogue Commission in his region of Colombia, with his main task being to create a peaceful discussion between the residents of his impoverished area and the government. Daza, who works in a coffee-producing cooperative in Nariño, works to extend food sovereignty and is a spokesperson of the Agrarian, Peasant, Ethnic and Popular Summit, a platform of people’s movements and organizations that has engaged in direct dialogue with the national government on a list of demands to do with the rights and livelihoods of rural communities. Gallo is a well-known peasant leader from eastern Arauca who works with Coagrosarare, an agricultural food cooperative; his political reputation was built on his defense of his community against the U.S. multinational company Occidental Petroleum. None of these people has any involvement with armed struggle or has any plans to launch an armed struggle. Their goal, however, is to advance the well-being of their communities, an agenda that runs up against the rigidity of Colombia’s oligarchy, whose political leader is Iván Duque.

A range of people’s organizations and human rights groups condemned these arrests. The Congreso de los Pueblos, in a widely circulated joint statement, said that these “arbitrary arrests”—and the long list of assassinations—have taken place because these social leaders think and act in ways different from the regime. After days of mobilization, on Monday, December 21, the judge overseeing the case granted bail to the three peasant leaders.

Bogotá Group

In 2017, at the urging of the United States government, a group of 12 governments from the American hemisphere met in Lima, Peru, to create a group whose express purpose is to overthrow the government in Venezuela. It is quite remarkable that these member states of the United Nations would pursue a project—regime change—that goes against the United Nations Charter of 1945 (they have no UN Security Council resolution under either Chapter VI or VII to justify their actions). This year, Peru entered a serious political crisis from which it has yet to recover; the appetite in Lima to lead the way against Venezuela is now virtually zero. It has fallen on Iván Duque to take up the mantle on behalf of the United States and Canada to try to overthrow the government of Venezuela. It would now be more fitting to change the name from the Lima Group to the Bogotá Group.

It tells you something about the character of the government of Duque that it has said it would not offer the COVID-19 vaccination to Venezuelans who live in Colombia with an irregular status; it says something too that Juan Guaidó, Washington’s Venezuelan, agreed with Iván Duque on this abominable decision.

Not long after the National Assembly election in Venezuela on December 6, the Colombians jotted down a statement of condemnation that was then co-signed by other members of the Lima Group (although Argentina, Bolivia, and Mexico did not sign). Claiming that the election was “fraudulent,” they made two demands: first, that the “international community” reject the elections, and second, that the political parties inside Venezuela should abandon the actual political process in the country and begin a “process of transition.” However, most of the world—outside the capitals of Europe and the United States—has not followed the example set by this group, and none of the actual political parties inside Venezuela has been drawn into its agenda. The conservative mainstream—led by COPEI and Acción Democrática—and the evangelical parties inside Venezuela believe that the National Assembly must begin work from January 5 to revive their country’s political sovereignty. They do not want any more interference from Washington or from Colombia.