The Japanese news agency Kyodo reported from Washington Sunday quoting “a source” that the Biden Administration had proposed to New Delhi, Tokyo and Canberra the idea of holding an online summit meeting of the leaders of the “Quad”.

The report added,

Whether the talks will materialise soon is up to India, which is known for its relatively cautious stance on the (Quad) framework. It is the only Quad member that shares a land border with China and operates out of U.S.-led security alliances.

President Joe Biden called up Prime Minister Narendra Modi on Monday and the topics discussed centred around close cooperation for “a stronger regional architecture through the Quad” in the backdrop of the developments in Myanmar.

According to the White House readout, Biden and Modi noted that a shared commitment to democratic values is the bedrock for the US-India relationship and “resolved that the rule of law and the democratic process must be upheld in Burma.”

On Tuesday, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken also called his Indian counterpart S. Jaishankar to discuss the coup in Myanmar. The White House readout said,

Both sides look forward to expanded regional cooperation, including through the Quad.

The decision to “upgrade” the Quad to the highest level of leadership is a major initiative by the Biden administration. The Quad overnight becomes the tip of the spear in the Indo-Pacific strategy. National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan recently signalled during an online event that Quad will play a key part in U.S. policy in the Indo-Pacific region facing China’s rise.

Sullivan said, “I think we really want to carry forward and build on that (Quad) format, that mechanism, which we see as fundamental, a foundation, upon which to build substantial American policy in the Indo-Pacific region.” Interestingly, Robert O’Brien, former national security adviser for Trump, also said at the same event that the Quad may be the “most important relationship we’ve established since NATO at a high level.”

Conceived in 2004 in response to the Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami but lying dormant for a decade thereafter, Quad was revived in 2017 by the Trump administration and has since rapidly grown, focusing on efforts to advance a “free and open” Indo-Pacific region. Indeed, the revival of Quad can be seen as a foreign-policy achievement of the Trump administration on an otherwise bleak foreign-policy landscape.

The Biden administration is moving quickly to build on Trump’s legacy. The upgrade of Quad becomes the new administration’s first major counter-offensive against China, consistent with Biden’s promise that diplomacy will be at the centre of his foreign policy. The strengthening of the Quad signifies that the U.S. hopes to create a more united–and enlarged–front of American allies to face China.

The military coup in Myanmar has come timely for the Quad to position itself as the platform to galvanise the restoration of democracy in that country and the promotion of human rights and democracy in the Asia-Pacific in general. This has profound implications.

China has brilliantly succeeded through the past decade in dominating and shifting the narrative in the Asia-Pacific to the economic agenda. The U.S. cannot possibly retrieve that lost ground. But, in the U.S. assessment, by positioning the Quad as the flag carrier of human rights and democracy in the Asia-Pacific, Washington could carve out a political domain where China is doomed to remain an outsider.

Put differently, Quad becomes a platform for rallying the ASEAN countries that have shown wariness so far to take sides between Washington and Beijing. Meanwhile, the Quad platform could potentially attract the U.S.’ European allies as well, such as Germany, who may otherwise have strong economic relations with China. Indeed, a whole lot of possibilities arise to turn the table on China and to isolate it in the region.

In short, the Myanmar situation will test the Quad’s efficacy as the fountainhead of democratic change in the region. Faced with the coup in Myanmar, the ASEAN has so far held on to the core principle of non-interference in the internal affairs of any member country. But ASEAN is a divided house on the Myanmar question.

The pro-western governments in Malaysia, Indonesia and Singapore have expressed deep concern, while Thailand and Cambodia, the two countries bordering Myanmar adhere to the cardinal principle of non-interference and Laos and Vietnam, the two communist countries in the region, are in empathy with the latter.

The U.S. National Security Advisor Sullivan called up the Thai National Security Council General Natthaphon Narkphanit Monday to express “concern over both recent arrests of Thai protestors and several lengthy lese-majeste sentences in recent weeks” as well as to convey “President Biden’s deep concern regarding the coup in Burma.” In effect, Sullivan warned the Thai military leadership against lending any form of support to Myanmar’s Senior General Min Aung Hlaing.

The Quad faces a formidable challenge to get the ASEAN on board over the situation in Myanmar. If it succeeds, the regional balance may tilt in favour of the U.S. But as things stand, the ASEAN may prefer to steer clear of geopolitics and seek a consensus favouring reconciliation between the military and the opposition. Indeed, the Myanmar military is also seeking a way out of the impasse and may be open to the good offices of ASEAN.

Similarly, the Biden administration also seeks to “lock in” India, which has traditionally followed a policy of constructive engagement of the Myanmar military. The Indian analysts underscore the criticality of cooperation and support that the Myanmar military has been extending to the security agencies to counter trans-border activities of militant / separatist groups operating in the country’s north-eastern region.

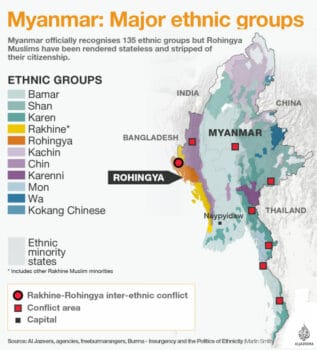

But, there is more–much more–to the impact on Indian interests. Fundamentally, Myanmar’s political economy is strikingly similar to India’s, being a multiethnic, multilingual, and multicultural society that attained independence from colonial rule and attained nationhood for the first time in modern history. The country encompasses eight main ethnic groups and further 135 indigenous ethnic groups..

The majority group Burman make up anywhere between half and two-thirds of the country’s population of 55 million. Succinctly put, the largest ethnic minority groups groups–Shan, the Karen, the Arakanese, etc.–stand outside the pale of power-sharing in Naypyitaw between the military and the democratic opposition (which largely represent the Burman).

The majority group Burman make up anywhere between half and two-thirds of the country’s population of 55 million. Succinctly put, the largest ethnic minority groups groups–Shan, the Karen, the Arakanese, etc.–stand outside the pale of power-sharing in Naypyitaw between the military and the democratic opposition (which largely represent the Burman).

Now, there is also a regional divide, since the majority Burman mainly live on the central plains, including the cities of Yangon and Mandalay, while ethnic minority groups live around the country’s mountainous borderlands. To compound matters further, the central valley of Myanmar inhabited by the majority Burman is surrounded by a horseshoe-shaped mountainous periphery that controls Myanmar’s overland access to neighbouring countries.

Besides, the periphery, which is home to the indigenous ethnic minorities, accounts for more than half of the country’s area and coastline, and holds most of the natural resources. Again, the Burman Buddhists in the central plains view Christianity as a threat, whilst the tribes on the periphery embraced Christianity as a counterweight to the majoritarian state in the post-colonial period. It is useful to recall that the two segments (Buddhists vs. non-Buddhists) fought on opposite sides during World War 2.)

It does not need much ingenuity to figure out that if constitutional rule breaks down due to protracted social unrest, almost inevitably, the ethnic minorities who possess highly distinctive national, cultural and language identities will begin to assert–especially, if the steel frame of the military were to weaken or disintegrate. In fact, no ethnic group will be able to assert as a unifying force. Meanwhile, the country is also awash with weapons.

Suffice to say, those who are charioting the Quad are unrealistic to show impatience with Myanmar’s transition to a flourishing democracy and are visualising the military coup in a rather textbook fashion. They betray a lack of understanding of the country’s complex institutional and ethnic topographies and the indigenous origins of its turn to democracy. Aung San Suu Kyi’s stubborn refusal to play the western game or to be party to the weakening of the Myanmar military during the Rohingya crisis–her strident nationalism–must be put in the above perspective. (This also partly explains why Suu Kyi drew close to China, much to the frustration of the West.)

Clearly, Myanmar’s ethnic cauldron is like a tinderbox. The Muslim Rohingya activists already sense that a defining moment is coming for their struggle for independence. The spectre of dismemberment of the former Yugoslavia haunts Myanmar.

The U.S.’ geopolitical considerations dictate that Thailand and Myanmar do not allow land corridors for China to the Indian Ocean to mitigate its so-called “Malacca Dilemma”. But, for the ASEAN countries–or India, for that matter—a dismemberment of Myanmar will almost certainly have domino effect.

The Quad is overreaching in the Biden Administration’s unseemly hurry to proclaim that “America is back.”