Scant attention has been placed on the context of anti-Asian racism and its roots in the history of U.S. imperialism.

Gimme that ball, gook.

Can you see with those eyes, chink?

Did your Dad get your Mom in Vietnam?

These were just some of the references to anti-Asian racism heard frequently throughout my childhood which were often accompanied by social humiliation and threats of violence, whether in the form of robbery (many times) or a puzzling curiosity about the size of my genitals. More politically correct adults would throw praise at my perceived “model minority” status. This sent an early message that the best means of surviving within a racist society was to focus on individual uplift and avoid conflict with those in power.

The U.S. mainstream has caught up with the existence of racism toward Asians in America, mainly because it has become harder to ignore. Violence directed at Asian Americans has skyrocketed since the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the Asian American Bar Association of New York, more than 2,500 cases of anti-Asian “hate incidents” have been reported across the country between the months of March and September of 2020. Notable cases include the January assault of an elder Thai man in San Francisco and the stabbing of a Chinese man in New York’s Chinatown last month.

The wave of violence has caught the attention of the Biden administration, the corporate media, and prominent celebrities. Former NBA and current G-League player Jeremy Lin took a strong stance against anti-Asian racism in late February. Lin’s post on Facebook came in response to being called “coronavirus” on the basketball court. His statement ended with a question: “Is anyone listening?” While more has been said in recent weeks about the rise of anti-Asian racism and the urgency to address it, scant attention has been placed on the context of anti-Asian racism and its roots in the history of U.S. imperialism.

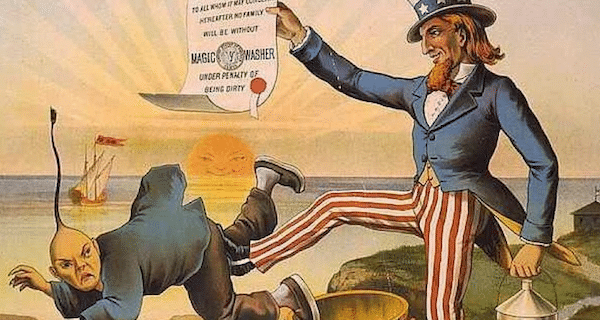

The United States was a willing participant in China’s “Century of Humiliation” following the Opium Wars of the early to mid-19th century. Prominent capitalists such as Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s maternal grandfather Warren Delano enriched themselves from the sale of opium, an industry imposed on China by way of treaties that massively displaced and impoverished the population. American gunboats sailed along the Yangtze protecting U.S. interests for nearly a century prior to the Chinese Revolution of 1949. Migrant Chinese workers in the United States were dehumanized as “coolies” to justify the white supremacist violence leveled against them, even by a large section of organized labor.

The dehumanization of peoples of Asian descent is often isolated and disconnected from the white supremacist violence experienced by Black and indigenous peoples in the United States. Yet the U.S.’s original sins of racialized slavery and settler colonialism helped form the material basis for the rise of anti-Asian racism. During the decade and a half-long U.S. occupation of the Philippines, U.S. soldiers justified mass slaughter and plunder by routinely equating the Filipino people with the same racist tropes used to describe Black Americans and Indigenous nations. Eventually, a unique language of racism was deployed to normalize not only the destruction of the Philippines but also the internment of Japanese residents and the brutal wars of aggression waged in Korea, Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia. As Black Americans faced the violence and exploitation of Jim Crow, the scope of white supremacy was widening in service of the U.S. project of imperialist domination.

However, U.S. imperialism has also required white supremacy to constantly shape shift to fit the interests of its ruling class. State violence and economic dislocation has unevenly affected the various nationalities that make up the “Asian American” umbrella. A concerted effort to “diversify” the U.S. mainstream with popular movies and programs highlighting of “Asian” riches has intensified the identification of Asian America as a privileged stratum far closer to white America on the class ladder than the U.S.’s oppressed and super exploited Black and Indigenous populations. The U.S. corporate media and political establishment has reinforced this generalization by paying close attention to forces in Asian American communities calling for more law enforcement protection against racist violence.

All of this combined has divorced anti-Asian racism from its roots in the development of U.S. imperialism. The separation of anti-Asian racism from U.S. imperialism has both encouraged a potential reliance on the state to resolve the very racist violence it commits with regularity and the systematic erasure of the real reasons behind the rise in anti-Asian racism in the United States. Just as the United States deployed racism to justify its empire-building in the Asia Pacific during the 20th century, so too has the U.S. ruling class intensified a deep skepticism of China amid the devastating spread of COVID-19 on the U.S. mainland. While the corporate media has acknowledged the role of Trump’s scapegoating of China for the spread of COVID-19, it hasn’t explained why the U.S. is so hostile toward China in the first place.

The truth is that “Kung Flu” and other racist tropes peddled by Trump and his legions are only one aspect of a larger U.S. campaign to contain the rise of China. China is set to surpass the United States as the world’s largest economy within a decade and has garnered favorable international attention for its containment of COVID-19 and its efforts to curb extreme poverty and climate breakdown. The rise of China has placed the hegemony of U.S. imperialism into question on the highest stage possible: that of the fundamental relations between nations and economies. This has spurred a U.S.-led New Cold War against China led by all sections of Washington’s establishment, including its most left-leaning elements.

The New Cold War on China is first and foremost a military campaign comprised of four hundred U.S. military bases, hundreds of thousands of U.S. troops, and over sixty percent of all U.S. naval assets stationed in the Asia Pacific. But the U.S. strategy to contain China includes political and economic sabotage. Sanctions have been placed on Chinese officials and tech corporations and the U.S. has waged an endless campaign of interference in China’s internal affairs relating to Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region and the city of Hong Kong. Both corporate and so-called progressive media such as Democracy Now have obsessively focused on the reproduction of negative stories that mirror the U.S. Department of State’s official posture toward China. The endless stream of anti-China propaganda has been effective; eighty percent of all Americans currently view China unfavorably, according to recent polls.

The only difference between the recent wave of intense anti-Asian racism and that which has endured over the course of U.S. history is the stage of the imperialist system. The U.S is no longer a rising empire. Rather, U.S. imperialism has entered a state of decay decades in the making and can only speak the language of military, political, and economic violence. The struggle against anti-Asian racism thus cannot be left to the militarized police forces terrorizing Black American communities or to the larger U.S. political apparatus that honed anti-Asian racism as a weapon of imperialist expansionism. Instead, U.S. hostility toward China and the peoples of the East should be seen as an opportunity to develop the broadest popular front possible toward the cause of peace, self-determination, and liberation from the oppressive rule of imperialism.