“The person attempting to travel two roads at once will get nowhere”. It’s a well-known Chinese maxim, especially in Myanmar (Burma), China’s backdoor to the Bay of Bengal, the Indian Ocean, and the Indian Navy’s forward defence line.

Russia’s policy towards Myanmar since the military takeover on February 1 is a case of proving the maxim mistaken. Although experts and officials in Moscow won’t say so aloud, it’s possible for Russia to pursue one strategy with two tactics; three more like.

The putsch by the Myanmar armed forces command (the Tatmadaw) was timed to prevent the first meeting of the parliament elected at the poll of November 8, 2020, when the majority of the anti-military National League for Democracy (NLD) increased by a landslide, and the future for the Tatmadaw’s control over the lucrative elements of the economy threatened directly. A state of emergency has been declared for a year; the civilian political leadership is under arrest; the armed forces have mobilized to crush public opposition. The casualty count is in the thousands; several hundred have been reported dead.

The military, led by General Min Aung Hlaing, claimed to be acting against vote fraud in the balloting. “Although the sovereignty of the nation must derive from the people,” the general’s television announcement said,

there was terrible fraud in the voter list during the democratic general election which runs contrary to ensuring a stable democracy. A refusal to settle the issue of voter list fraud and a failure to take action and follow a request to postpone lower-house and upper-house parliament sessions is not in accordance with article 417 of the 2018 constitution that refers to ‘acts or attempts to take over the sovereignty of the Union by wrongful forcible means’ and could lead to a disintegration of national solidarity.

Right: Kavi Chongkittavorn is also associated with a Thai think-tank funded by the US, Canada and the Swiss government.

The Irrawaddy, a relatively independent, pro-democracy newspaper in the country, editorialised on what had happened with the Thai analyst, Kavi Chongkittavorn.

Sad as it is, the singular question needs to be asked: Why does Myanmar find itself in this black hole? Who failed Myanmar? Frankly, the answer is quite simple—everyone who is involved, directly and indirectly.

While the international community, especially the UN, has been ferocious in its condemnation of the atrocities committed by the Myanmar military (or Tatmadaw) since its power seizure on Feb. 1, it has been completely forgotten that this horrible situation was not only of the Tatmadaw’s making. It takes two to tango; in this case, the National League for Democracy (NLD) and the Tatmadaw locked horns, leading to a breakdown. Indeed, the positions and personalities of those institutions’ leaders—Daw Aung San Sun Kyi and Senior General Min Aung Hlaing—and their perceptions of one another, must be factored in.

The Tatmadaw has sought to maintain what it sees as its political legitimacy throughout Myanmar’s nascent experiment with parliamentary democracy, as stipulated in the 2008 Constitution. The NLD, meanwhile, emboldened by its overwhelming poll victory in November, believed falsely that it could govern Myanmar solely and proceed with long-delayed constitutional amendments to reduce and eventually eliminate the military from the political arena—perhaps for good.

The Russian Foreign Ministry knows this; it has carefully avoided saying so. Instead, it issued a brief response on February 1 neither endorsing the takeover nor condemning it. “We are following closely developments in the Republic of the Union of Myanmar,” announced the ministry spokesman Maria Zakharova. “Unfortunately, the main political forces of this country failed to resolve the differences that arose following the results of the parliamentary elections held in November 2020. We hope for a peaceful settlement of the situation in accordance with the current legislation through the resumption of political dialogue and the preservation of the country’s sustainable socio-economic development. In this regard, they drew attention to the statement of the military authorities about their intention to hold new parliamentary elections a year later. We recommend that Russian citizens in Myanmar avoid crowded places.” This statement implied condemnation of the arrests and of the subsequent violence.

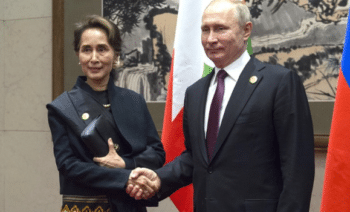

Aung San Suu Kyi meeting with President Vladimir Putin in China on April 26, 2019. Source: http://en.kremlin.ru/

In the weeks between the November election and the putsch, the Foreign Ministry had been issuing brief but supportive bulletins balancing between the Tatmadaw and the civilian government led by the Anglo-American icon, Aung San Suu Kyi. On November 19, the ministry endorsed the vote as an “an important milestone in Myanmar’s progress along the path of democratic development and national reconciliation. Despite the continuing difficult situation in certain regions, the election campaign and voting took place in an overall stable and peaceful environment and in accordance with Myanmar’s legislation and was marked by a high turnout. We reiterate our principled commitment to further strengthen the traditionally friendly Russia-Myanmar relations and mutually beneficial multifaceted cooperation in the interests of the peoples of our countries.”

On December 21 Nikolai Listopadov, the Russian Ambassador in Myanmar, published a summary of his discussion with U Chan Aye, Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Myanmar. “The parties discussed the development of friendly Russia-Myanmar relations, exchanged views on the positions of Russia and Myanmar on international platforms, including in the UN, which, as it was stated are close or coincide”. The ambiguity in the last three words is the telling one–two roads at once.

Ambassador Listopadov is fluent in the Burmese language, a point Aung San Suu Kyi mentioned with approval in her meeting with President Putin in 2019. Source: https://www.mid.ru/

As the domestic situation worsened, the last Foreign Ministry statement was on March 3:

It was noted that the situation in Myanmar had been discussed during the informal meeting of ASEAN [Association of Southeast Asian Nations] Foreign Ministers on 2 March. We share the call made in the statement of the Brunei presidency of the ‘dozens’ to all parties to avoid further violence and to exercise maximum restraint and flexibility, to seek a peaceful solution through constructive dialogue. We hope that the position of Myanmar’s neighbors in the region will contribute to the normalization of the situation in this country. We are ready to cooperate with ASEAN in this direction both on international platforms and within the framework of aseanocentric mechanisms.

The strategic principle is non-intervention in the domestic affairs of Myanmar. The tactic has been to avoid beating breasts in public, as the former colonial power in London has been doing, and its successor in Washington. “Aseanocentric” meant–John Bull, Yankee stay out.

The second Russian tactic has been to prevent the Anglo-American attempt at the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) to legislate for coordinated international sanctions, as well as intervention across Myanmar’s borders. Russia and China used the threat of their Security Council veto to stop a British initiative, and lowered both the level of threat and the legal authority of intervention to a UNSC statement, not a resolution. India and Vietnam also joined the bloc against the Anglo-American thrust. None of this is new policy. Tempering and blocking have been consistent Russian tactics for Myanmar at the UN for more than a decade.

The UNSC’s statement of March 10, agreed with Russia and China, registered “deep concern at developments in Myanmar following the declaration of the state of emergency imposed by the military on 1 February and the arbitrary detention of members of the Government, including State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi and President Win Myint and others. The Security Council reiterates its call for their immediate release.”

There was no agreement on Anglo-American sanctions or for cross-border intervention, including increased arms supplies to the ethnic armies of the northern regions. Camouflage for air drops was included in the sentence: “The Security Council continues to call for safe and unimpeded humanitarian access to all people in need”. The last sentence ruled out such secret operations.

The Security Council reaffirms… its strong commitment to the sovereignty, political independence, territorial integrity and unity of Myanmar.

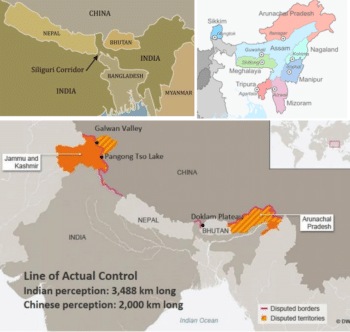

THE STRATEGIC SITUATION MAP OF MYANMAR

THE STRATEGIC SITUATION MAP OF MYANMAR

On Russia’s map of eastern and southeast Asia, compared to China, India, Vietnam, Thailand, Indonesia, and Malaysia, Myanmar plays a minor part in trade, tourism, and business investment. Russia warfighters in the British and U.S. governments exaggerate this. A Norwegian think-tank report in 2017 judged Russian policy toward Myanmar to be aimed at countering U.S. efforts at isolating and attacking China.

At President Putin’s meeting with State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi in China two years ago, Putin had said: “We are committed to the further development of political dialogue and the continuation of inter-parliamentary exchanges. Our ministries of foreign affairs also have well-established contacts. Although quite modest in absolute terms, our mutual trade is growing rapidly, having gained more than 50 percent last year.” Putin wasn’t counting the arms trade.

This is the third of Russia’s Burma roads–the military relationship with the Tatmadaw has been considerable and growing steadily. The supplies have included combat and trainer aircraft for the air force–MiG-29, Su-30MK, Mi-24 and Mi-35P helicopters–armoured vehicles for the army and police, anti-aircraft missile batteries, electronic surveillance and counter-measures, and to come–the Pantsir-S1 air defence system, Orlan-10E surveillance drones and radar equipment. The programme has also included Burmese officer training in Russia.

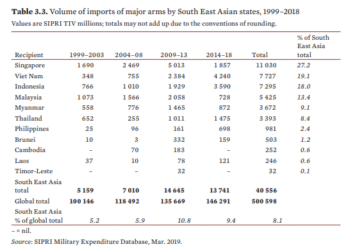

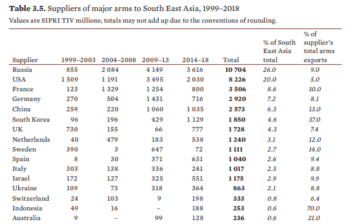

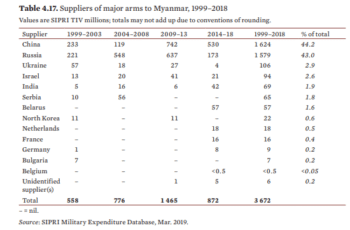

According to the 2019 study by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), Russia is the second arms supplier to Myanmar after China, accounting for 20% of its procurement from 2014-2018; 43% over the period, 1999-2018. By contrast, China has provided 61% and 44%, respectively. Myanmar spent $2.4 billion on weapons from 2010-2019, including $807 million on Russian-made arms. The money spent has generated a 96% increase in Myanmar’s military inventory between 2008 and 2017–the biggest growth of any of the southeast Asian states.

The U.S. government tried to stop it; it failed. China, Russia and Israel have all supplied arms to the Tatmadaw when the U.S. and European Union states observed an arms embargo.

According to SIPRI,

disputes over maritime boundaries, most notably with Bangladesh where oil and gas are at issue, are likely to have partly driven higher levels of spending.These maritime issues would explain the expansion of the navy over the past decade from a limited coastal force to a force of several frigates that provides some blue-water capabilities, and the interest in submarines.

To date, the Myanmar navy has been equipped with larger vessels from India, China and the U.S.; smaller ones have been sold by Israel or built in local shipyards. Russia’s role to date has been to provide shipboard weapons and other technology, including equipment for the new Burmese submarine force. The Russian Navy is expected to establish regular portcall facilities on the coast.

Source: https://www.sipri.org/

Myanmar’s expenditure data for arms are almost certainly under-estimates.

The list of military purposes identified at the signing of the 2016 defense cooperation agreement between the two countries, and the list of officers identified in General Min Aung Hlaing’s April 2019 visit to Moscow show how extensive the military supply relationship has become.

High-level Russian defence ministry visits to Myanmar just before the putsch and since then reinforce the third road approach. On January 21-22, Defence Minister Sergei Shoigu (lead image) held talks in Naypyitaw (Yangon, Rangoon) with the Tatmadaw. They finalised an agreement to deliver the Pantsir and other equipment.

The Irrawaddy reported:

it is not yet known where Myanmar’s military… plans to deploy the Pantsir-S1 anti-aircraft missile system, but military analysts suspect it will be positioned along the border with Bangladesh. The Irrawaddy has learned that the anti-aircraft missile system could also be deployed in Shan State, close to the Wa Self-Administered Zone controlled by the United Wa State Army (UWSA), Myanmar’s largest ethnic armed organization. In February last year, China provided military hardware, drones and training to the UWSA. The organization confirmed it had acquired a helicopter, making the northeast-based rebel group the nation’s first to possess such an aircraft. The helicopter was reportedly ordered and delivered from China.

In October 2020, when the Tatmadaw navy conducted its annual exercises, it showed off the UMS Min Ye Thain Kha Thu, a Russian-made attack submarine. This is a Kilo-class vessel, provided by the Indian Navy; it was designed by the Rubin Central Maritime Design Bureau in St. Petersburg.

The price and payment terms for the new Russian arms have not been revealed.

On March 12, the Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov was quoted as saying: “We assess the situation as alarming, and we are concerned about the information coming from there about the growing number of civilian casualties. This is a matter of worry for us. We are very closely monitoring what is happening there.” That was the Foreign Ministry line.

Peskov added that Moscow was “also weighing the possibility of suspending military cooperation with Myanmar.” This was no one’s line, certainly not the Russian Defence Ministry’s.

The visit on March 26 to Yangon of Russian deputy defence minister General Alexander Fomin has been dramatised in the Anglo-American media as a show of Russian support for military force in the country. Fomin, however, was not the only foreign military representative at the Tatmadaw military parade that day. India, Bangladesh and China were also demonstratively present.

BEFORE: the Russian military delegation, led by Sergei Shoigu (right), meets the Myanmar delegation in Naypyitaw (formerly Yangon, Rangoon) on January 22, 2021. Note the Myanmar Navy commander, Admiral Tin Aung San, second from left.

Fomin has been quoted in the Russian press as backing a “strategic” relationship with Myanmar. The leading daily newspaper of Moscow, Moskovsky Komsomolets, published a highly unusual interview with Min Aung Hlaing at the same time. Min Aung Hliang tried accentuating the positive; Pavel Gusev, the MK editor in chief, eliminating the negative.

“Russia is an old and loyal friend to us,” the general said.

The law enforcement forces and the army serve to protect the safety of citizens” Gusev said, adding “all the dirty methods of the ‘colour revolutions’ are used against them. Events often develop according to the scenario known since the Maidan in Kiev.

According to Min Aung Hliang,

I would like to invite the Russian side and Russian businessmen to participate in these projects. We need your technologies that will help us develop the manufacturing industry and mechanical engineering… you have very developed technologies for processing agricultural products. In Myanmar, fresh fruit is grown all year round. And, as a rule, they are also consumed fresh. You could help us organize the production of canned vegetables and fruits. Why not? This would help to increase the export of our agricultural products to Russia.

On January 22 General Min Aung Hlaing and Defence Minister Shoigu exchanged a ceremonial sword and medal.

The general also promised to investigate why Russian tourism to Myanmar has been dropping off, and to consider offering a visa-free regime. “I agree”, he told Gusev,

that the need for a visa is one of the factors that complicate the arrival of tourists. Your businessmen and rich people have flown to us on their private planes, including as tourists. We had a significant flow of Russian tourists. But then their number decreased. The reason is still unknown to me. I think that I, together with the relevant departments, will deal with this issue, find out the reason. Most likely, the issue is the weak economic ties between Russia and Myanmar. If your investments came to us, then tourism would also develop.–But for the development of mass tourism, the issue of a visa is important.

AFTER: left; General Alexander Fomin, Deputy Russian Defense Minister, receiving a medal from General Min Aung Hlaing, in Yangon on March 26, 2021. Right, Pavel Gusev, editor in chief of Moskovsky Komsomolets (MK), at the start of interview with Min Aung Hliang on March 26, 2021.

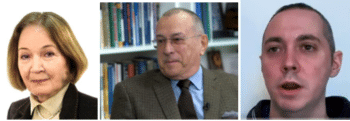

Russian military experts in Moscow say they have not been following the military relationship closely. One commented that Moscow’s policy at present is for stability in the country, not for taking sides–“Russia is going to work with any leader up to the task in Myanmar”. Two of Russia’s acknowledged experts on Myanmar, Aida Simonia, a researcher at the Centre for Southeast Asia at the Russian Academy of Sciences, and Gleb Ivashentsov, ambassador to Myanmar from 1997 to 2001, were asked if they detect a difference of assessment or policy between the Russian Foreign Ministry and Defence Ministry. They declined to reply.

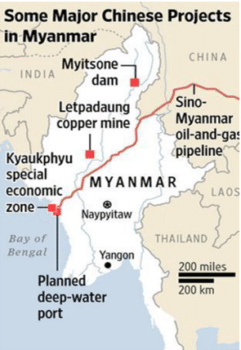

The Chinese government directs the largest foreign investment in Myanmar, and to the east guards the longest of Myanmar’s borders–2,129 kilometres. Min Aung Hlaing and Aung San Suu Kyi do not differ on the priority they assign to preserving their relationship with Beijing.

Left: Dr Aida Simonia; centre, Ambassador Gleb Ivashentsov; right, Alexander Gabuev. Gabuev, a former Kommersant reporter, is currently employed by U.S. think-tank, the Moscow Carnegie Centre, to direct its Russia in Asia-Pacific section. He is also employed as a “Munich young leader” in the NATO-led Munich Security Conference. His Twitter stream supports Moscow protests for Alexei Navalny, ignores the Myanmar events entirely. Gabuev volunteered anti-Russian comments to a Financial Times report headlined “Russia strides into diplomatic void after Myanmar coup” but he was unable to answer questions about the Foreign and Defence Ministry’s approaches to Yangon.

Along and across that frontier China has been supplying arms to both the Tatmadaw and to several of the ethnic forces in permanent rebellion against the government in Yangon. They include the United Wa State Army (UWSA), the Ta’ang National Liberation Army, the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army, and the Arakan Army (AA). Follow the history of British, Japanese, Chinese and U.S. involvement in the Burmese opium and methamphetamine trade, the ethnic army wars, and the evolution of military and civilian power-sharing in Yangon in this essay by London-based analyst, Gary Busch.

Busch also notes that China’s need to retain the southward flow of river water to generate electricity creates a long-term disadvantage for Myanmar and other downstream countries.

Myanmar is in a strategic location in the struggle by China to resolve its water supply problem. In a recent study, it was pointed out that China has 20 percent of the world’s population but only seven percent of its fresh water. And 80 percent of China’s water is in the south, whereas half of its population and two-thirds of its farmland are in the north. While total water usage in China increased by only 35 percent between 1980 and 2010, water usage in households increased elevenfold and in industrial sectors, threefold. But per capita available water in China amounts to only a quarter of the world average. Climate change will also increase China’s vulnerability to water scarcity… China’s water diplomacy in the region is a major destabilizing force and one which will have devastating consequences for its neighbours, including Myanmar.

The February coup by the Tatmadaw was not an unmixed blessing for the Chinese, particularly because of the violent civilian protests against the coup saw the destruction by the locals of eighty-three Chinese factories whom the civilians blamed for unfair labour practices and widespread pollution of the environment through spillages and polluted air. The Tatmadaw were less than supportive of the Chinese, which angered their Chinese overseers and partners. The Tatmadaw had made a lot of money collecting fees and owning shares in Chinese operations in ethnic areas but knew that the military support of the ethnic armies also came primarily from China and the drug smugglers who operated with Chinese blessing. The Chinese had some of their power in Myanmar curtailed by the retreat of the Tatmadaw in face of the NLD. The coup restricted them further.

The future of China’s hydroelectric, port, mining, and gas and oil projects in Myanmar is at risk if domestic opposition to the Tatmadaw’s putsch generates chronic chaos. A Hong Kong analyst reports that from Beijing’s perspective,

the coup does not serve Beijing’s interests. A stable political environment in Myanmar [is needed] for BRI [Belt and Road Initiative] projects to thrive. To them, Chinese leaders would prefer to work with the Aung San Suu Kyi… rather than the military junta.

The Indian assessment is that there can be no advantage in taking sides in protracted domestic conflict. “New Delhi,” reports a retired Indian diplomat, “attaches high importance to the security cooperation with Myanmar. This reflects a realistic assessment that the Myanmar military remains an enduring factor in regional politics and current history. A ‘boycott’ of the military is impractical while cordial ties have proven to be helpful to safeguard the security of the volatile northeastern regions.” The Indian Government regards American, Japanese and Australian efforts (the anti-China Quad–Quadrilateral Security Dialogue) to attack the Tatmadaw as “clumsy”.

The Indian military suffers from the serious geographic disadvantage that its border with Myanmar–1,468 kms long–cannot be reinforced quickly through the narrow Siliguri corridor.

Indian strategy is therefore opposed to covert western intervention in Myanmar destabilising its border regions with the objective of “bleed[ing] the Myanmar military in a protracted guerrilla war with the minority ethnic groups in the remote lawless border lands.” It is equally uncomfortable with what New Delhi views as propaganda incitement from the BBC and Radio Free Asia, the U.S. organ. From the Indian perspective,

that leaves Russia as the mainstay of support of Myanmar military (aside from the Thai military next door, which is also combating separatism by pro-western ethnic groups.)

For Russia, weaning the Indians away from the U.S.-directed Quad is almost as important as preserving the strategic alliance with China, also against the U.S. It is thus in the common interest of the Troika–Russia, China and India–for Myanmar to be stable enough to allow Chinese trade to move into the Bay of Bengal, bypassing the chokepoint controlled by Singapore for the U.S. at the Malacca Strait.

“Ideally,” comments the Indian source,

“Ideally,” comments the Indian source,

this should be a joint Russian-Indian-Chinese common enterprise of three emerging powers with overlapping strategic interests to transition toward a democratised world order away from the oppressive, unequal western-dominated one of present-day. That may appear wishful thinking in the prevailing circumstances.

According to Busch in London,

the solution to the problem of Myanmar is very complicated; especially since there seem to be no “good guys” to rely on except for the [Myanmar] workers. They deserve the world’s support but there seems to be no easy way to do so.