It is one year to the day since the World Health Organisation (WHO) declared the COVID-19 outbreak or epidemic as a ‘pandemic’, namely the global spread of the disease. Of course, COVID-19 had emerged much earlier, maybe even in autumn 2019, but the outbreak really took hold in Wuhan, China first, before quickly sweeping across the globe.

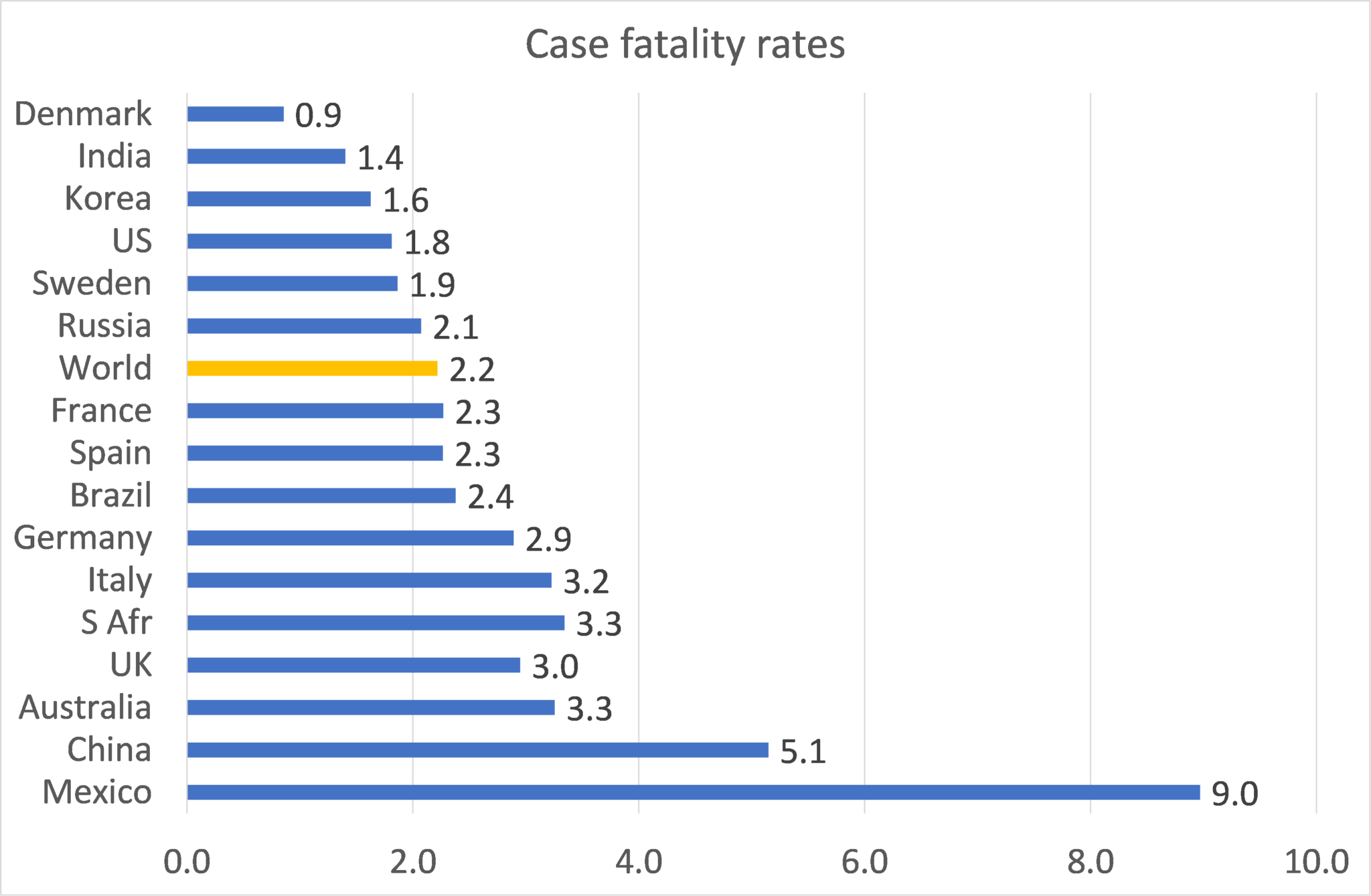

How does the health balance sheet look after one year of the pandemic? Well, 119m people (or just 2% of the world’s population) have been reported as infected, although if we include those who had no symptoms and those who did not report being ill, the figure is probably more like 15-20%. There have been 2.6m reported as having died of the disease. So that’s a case fatality ratio (CFR) of 2.2% globally. In some countries the CFR is way higher–Mexico’s CFR is close to 9%; Italy, the UK and South Africa CFRs are close to 3%. The variation is down to the age of those infected, the general health of the population and the resources and efficacy of the health systems in each country.

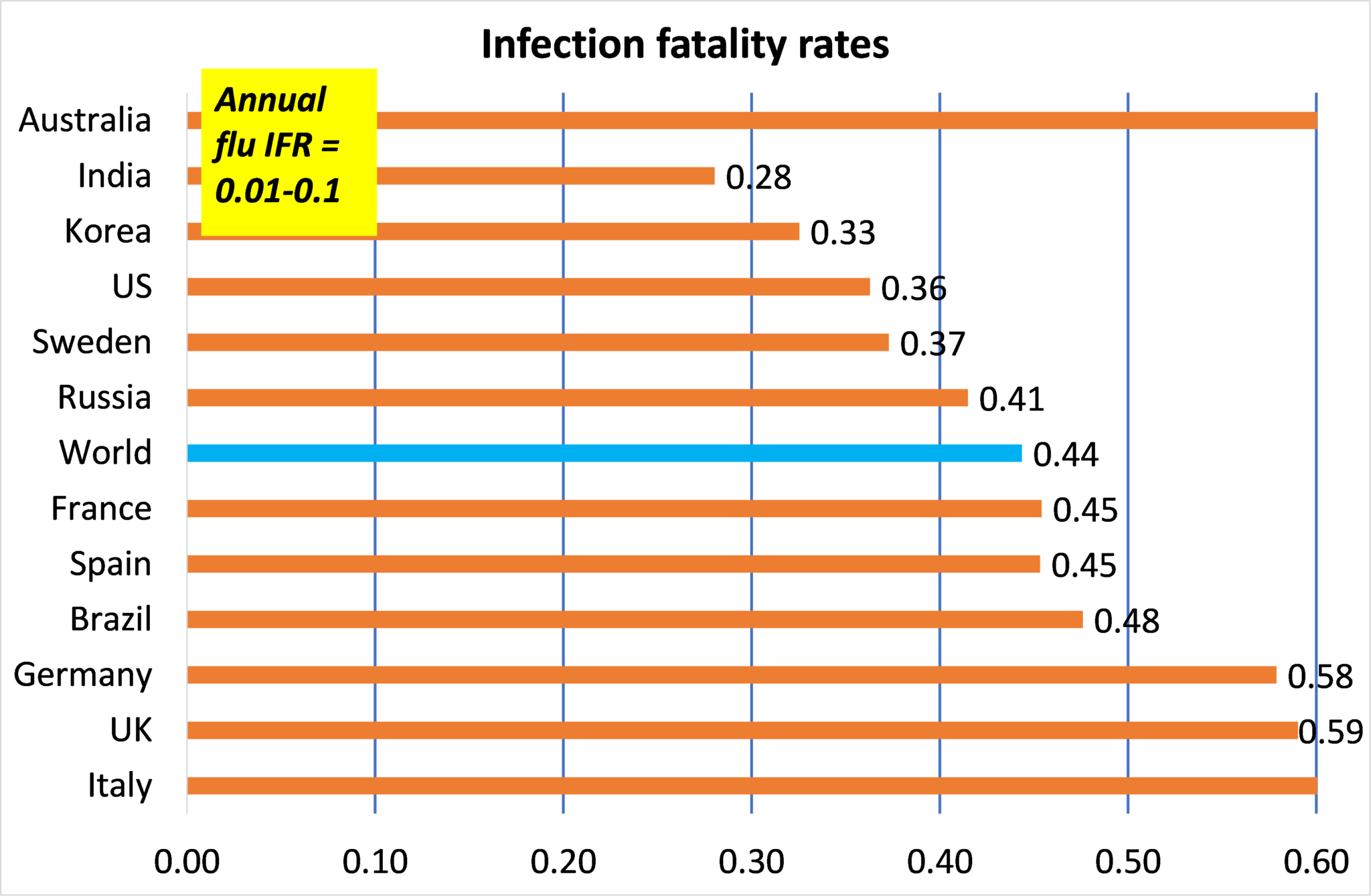

The case fatality ratio is different from the infection fatality ratio (IFR). If we make a reasonable assumption that around 15-20% of the world’s population have been infected, then we find that the IFR is about 0.44%, with many countries in Europe having much higher rates. For example, France at 0.67%; the UK at 0.59%; Italy at 0.65%; Germany at 0.58%. The U.S. IFR is below the world average at 0.36%. These are my estimates and subject to debate as nobody really knows the IFR. Micro studies in various parts of the world over the last year suggest that the IFR is probably between 0.5-0.7%.

These estimates suggest that COVID-19 is way more deadly than the average annual death rate from flu. That is around 0.1% max; so COVID-19 is probably at least five times more deadly. And also, we now know that COVID has the added issue of long-term damage to many sufferers, unlike flu.

And there is no doubt that the mitigation measures of social distancing, masks, varying degrees of lockdowns, improved medical treatments etc have reduced the death and long-term illness rate. If there had been none of these measures, and assuming the bug would not have died out until there was ‘herd immunity’ (approximately 60-70% of the population being infected), then around 20m people could have died.

And the incredible achievement of getting effective vaccines developed and distributed within the last few months is now helping to beat the pandemic. With any luck, the WHO will be declaring an end to the pandemic some time this year; while the number of future deaths and severe illness will be curbed.

But what of the impact of the last year’s pandemic on the world economy and people’s livelihoods? I have done several posts in the last year on the devastating hit to the world’s output, employment, investment and trade–as well as the social damage of isolation and immobility.

One thing is clear after a year of the pandemic. Those countries that failed to deal with the virus early and effectively; did not have sufficient health systems in place; or test and trace; and/or firm lockdowns, were the ones with the highest death rates AND the deepest hit to the economy and livelihoods. So there was no trade-off between lives and livelihoods, as claimed by the likes of Trump, Bolsonaro, etc and other right-wing pro-business groups.

Take the UK economy in 2020. It was the hardest hit of the top G7 economies in the year of the COVID. Real GDP fell 9.9%, the worst contraction in national income in 300 years! But the UK government also failed to protect the people from COVID-19. Following a resurgence of infections over the winter, around 1 in 5 people in Britain have so far contracted the virus, 1 in 150 have been hospitalised and 1 in 550 have died, the fourth highest mortality rate in the world.

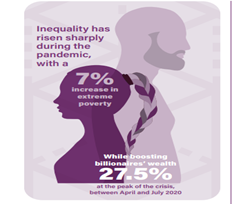

And of course, the virus has discriminated. While hundreds of millions have lost their jobs, businesses and incomes and been forced to go to work; others have stayed at home on full pay, saved money and are cash-rich. And the tiny elite that rule our globe have made a ‘killing’ on the financial markets, fuelled by a huge injection of credit by central banks and direct financial support by governments, mainly in the richer ‘global north’. In the year of the pandemic, billionaires’ wealth soared by 27.5 percent while 131 million people were pushed into poverty due to COVID-19.

And take Latin America. In its latest annual report, the UN’s Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) estimates that the total number of poor people inthe region rose to 209 million by the end of 2020, which is 22 million more people than in the previous year. According to ECLAC, as a result of the steep economic recession in the region, which will notch a -7.7% drop in GDP–it is estimated that in 2020, the ‘extreme’ poverty rate was 12.5% while the poverty rate affected 33.7% of the population. “The effects of the coronavirus pandemic have spread to all areas of human life, altering the way we interact, paralyzing economies and generating profound changes in societies,” the report said.

And take Latin America. In its latest annual report, the UN’s Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) estimates that the total number of poor people inthe region rose to 209 million by the end of 2020, which is 22 million more people than in the previous year. According to ECLAC, as a result of the steep economic recession in the region, which will notch a -7.7% drop in GDP–it is estimated that in 2020, the ‘extreme’ poverty rate was 12.5% while the poverty rate affected 33.7% of the population. “The effects of the coronavirus pandemic have spread to all areas of human life, altering the way we interact, paralyzing economies and generating profound changes in societies,” the report said.

Urban slums on the fringes of many of the region’s cities often lack access to basic services, mean many citizens found themselves unable to access food, water and healthcare necessary to confront the crisis.

According to the document, inequality in total income per person is expected to have grown in 2020, leading to the average gini index of inequality being 2.9% higher than recorded in 2019. Without the transfers made by governments to attenuate the loss of wage income (the distribution of which tends to be concentrated in low and middle income groups), the increase in the average gini index for the region would have been 5.6%. The pandemic has also brought a rise in mortality that could push down life expectancy in the region depending how long the crisis endures, the agency said. Of every 100 infections last reported around the world, about 24 were reported from countries in Latin America and the Caribbean.

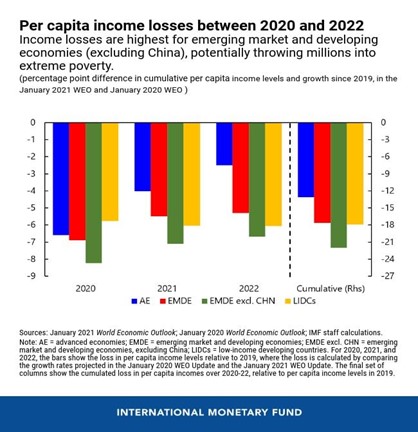

IMF chief Georgieva reports that by the end of 2022, cumulative per capita income will be 13 percent below pre-crisis projections in advanced economies—compared with 18 percent for low-income countries and 22 percent for emerging and developing countries excluding China. “Put another way, the convergence between countries can no longer be taken for granted. Before the crisis, we forecast that income gaps between advanced economies and 110 emerging and developing countries would narrow over 2020–22. ..But we now estimate that only 52 economies will be catching up during that period, while 58 are set to fall behind. ..There is a major risk that most developing countries will languish for years to come.”

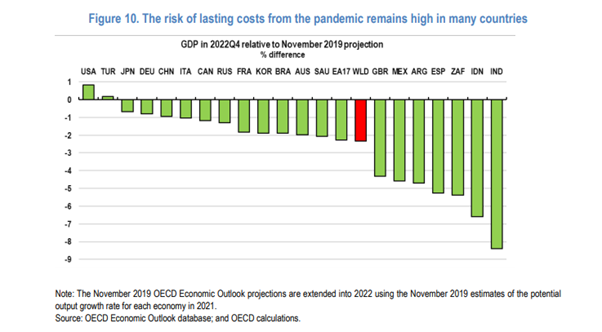

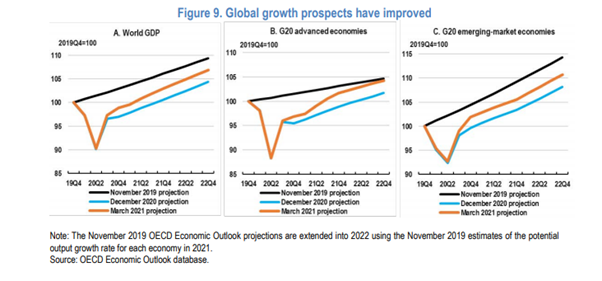

But the vaccines are here and economic recovery is now on the agenda. According to the latest OECD Economic Outlook, global GDP growth is projected to be 5½ per cent in 2021 and 4% in 2022, with global output rising above the pre-pandemic level by mid-2021. This sounds good, but as the OECD goes on to say, “despite the improved global outlook, output and incomes in many countries will still remain below the level expected prior to the pandemic at the end of 2022.”

In other words, there looks like being permanent ‘scarring’ of most economies as a result of the pandemic slump of 2020, with most economies never returning to the pre-pandemic growth and trajectory–which was already lower than the trajectory before the Great Recession hit in 2008.

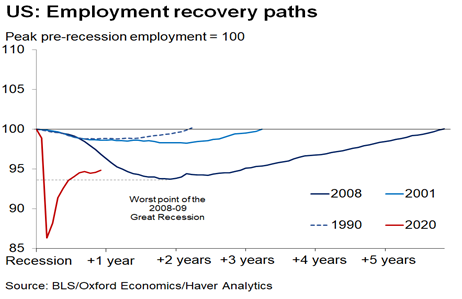

Even the U.S. has a long way to go to restore employment levels existing before the pandemic.

As I have argued before in several posts (search “pandemic”), this means the economic recovery will not be V-shaped or fast, but instead more like a ‘reverse square root’ shape when real GDP, investment and employment growth remain below previous rates indefinitely–suggesting another leg in the Long Depression that ensued after 2009.

The current view in the mainstream is that the U.S. economy will avoid less ‘scarring’ than other major economies, with the exception of China. And that’s because much hope is placed in new U.S. President Biden’s fiscal stimulus plans. The first stage of these plans has found its way through the U.S. Congress. The proposed huge $1.9trn measure has been watered down and the campaigned for increase in the minimum wage to $15 an hour has been dropped. But even so, the IMF reckons that,

the significant fiscal stimulus in the United States, along with faster vaccination, could boost U.S. GDP growth by over 3 percentage points this year, with welcome demand spillovers in key trading partners.

But the fiscal stimulus so far is just COVID support. Biden plans further spending on infrastructure, green projects and employment support. In previous posts, I have discussed how successful these will be given the state of the capitalist sector in the U.S. economy (and for that matter in other economies too).

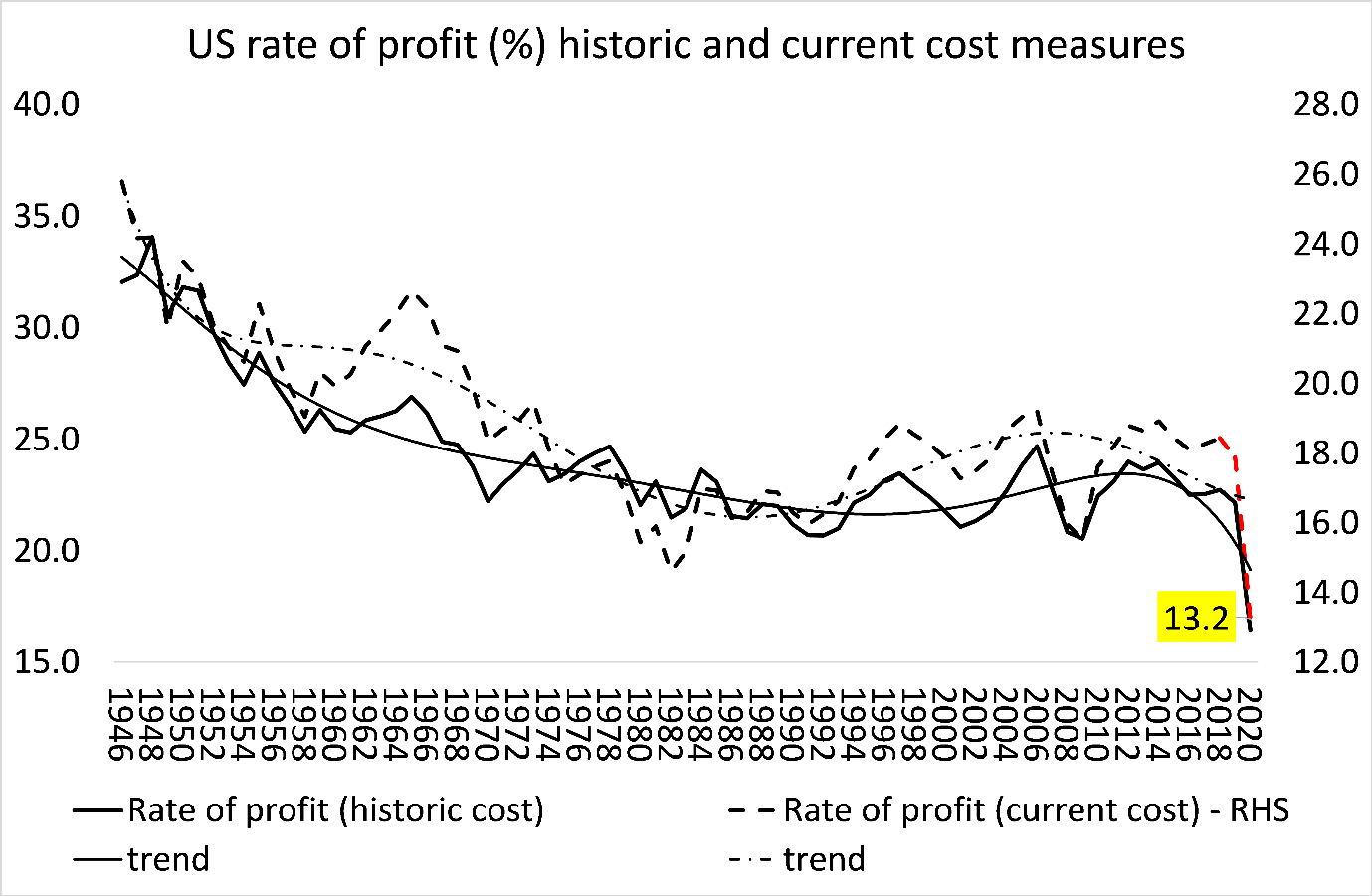

I have identified two factors likely to weaken the ability of the so-called Keynesian fiscal ‘multiplier’ to work sufficiently to boost and sustain economic recovery to new heights. The first is profitability. In a capitalist economy, the business sector rules and business investment dominates. And business investment will not be stimulated by fiscal handouts unless the profitability of capital rises sufficiently. In the year of the pandemic, the profitability of capital in the major economies hit an all-time low. This is the average profitability of the whole sector. Yes, the tiny group of tech companies, the FAANGS, have never had it so good. But their huge rise in profits is not matched in the rest of the business sector.

And when it comes down to it, the only really sustainable way to raise profitability across the board would be to cut the size of the workforce, get rid of ‘unproductive’ workers; merge, consolidate or liquidate weaker firms; and so create the conditions for better profitability through investment in new labour-saving technology. That’s possible down the road. But for the moment, those ‘unproductive workers’ are being mostly kept on the company books or supported with social benefits; while small and weak companies are being kept above water with cheap loans and other support.

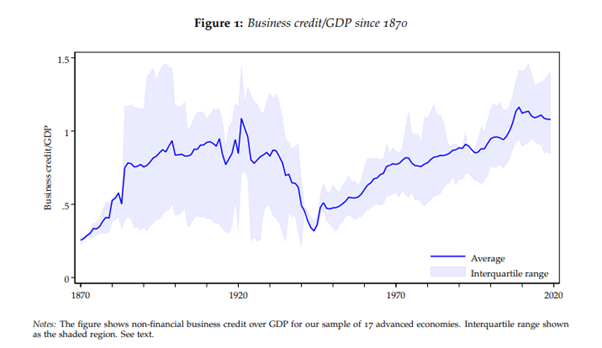

But that creates the second factor holding back sustained recovery in the capitalist sector: rising corporate debt, now near an all-time high in all the major capitalist economies.

In many previous posts (search debt), I have outlined the scale of rising corporate debt and how it has created so-called zombie companies that survive to pay wages and interest on their debt, but do not expand investment or employment. They are a weight around the neck of the capitalist sector. One recent study argued that “business debt can be restructured quickly, so “damage from debt overhang is not common. However, the after-effects of business debt booms become more problematic when debt restructuring and liquidation become more costly.” In places and times where reorganization and restructuring is inefficient and costly, “corporate debt overhang is an important macroeconomic force that has measurably negative effects at business cycle frequency.” (they mean expansion). Zombies at Large? Corporate Debt Overhang and the Macroeconomy (econtribute.de)

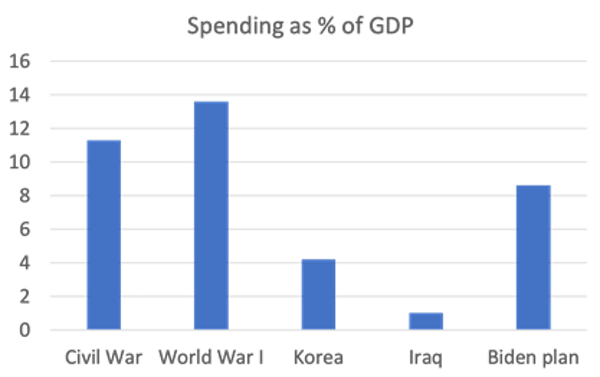

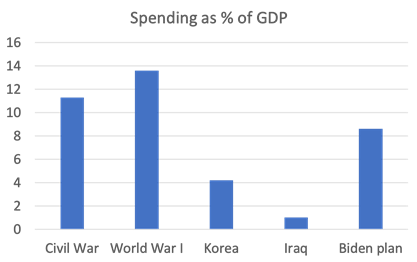

So the capitalist sector is in no state to engender a sustained economic recovery, even with more fiscal stimulus from Biden and the European Commission coming this year and next. And Biden’s package, although apparently large, is not really by historic standards. You could say it is the largest in peace time, but then the impact of the COVID pandemic in the last year is like a world war. What is needed is what some call a ‘war economy’, where the state steps in to replace the capitalist sector and directs resources for recovery, whatever the profitability outcomes. In WW2 government spend and investment was way higher than anything Biden plans. But as Keynesian Paul Krugman pointed out in the recent post,

World War II, which was vastly bigger but also took place in the context of a controlled economy.

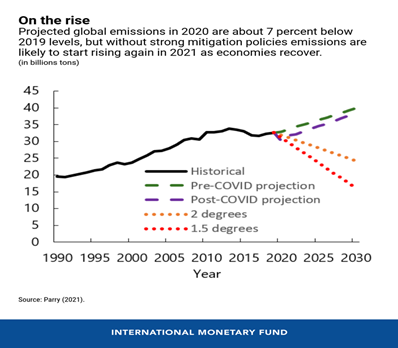

I don’t like the term ‘war economy’; better to call it a ‘social economy’ aiming to replace the capitalist sector. But that is what is needed, because the challenges facing the capitalist economy in the longer term are huge. With economic recovery, the speed-up in global warming and carbon emissions has returned, with little sign that governments are going to curb it sufficiently.

And capitalist firms are getting ready to shed labour for more technology, such as robots and AI. Big Tech companies including Amazon, Alibaba, Alphabet, Facebook, and Netflix are responsible for more than $2 of every $3 spent globally on AI (McKinsey Global Institute 2017). Workers will lose their jobs in many sectors because it will be the employers who decide, without any plan to use technology to reduce hours, retrain and create new jobs.

The pandemic has certainly given employers more reasons to look for ways of substituting machines for workers, and recent evidence suggests they are doing so. ( COVID-19 and Implications for Automation | NBER

As Daron Acemoglu at MIT puts it: “when employers make decisions about whether to replace workers with machines, they do not take into account the social disruption caused by the loss of jobs—especially good ones. This creates a bias toward excessive automation.” Acemoglu concludes that, with the next phase of automation rapidly unfolding, driven by machine learning and artificial intelligence (AI), the world’s economies stand at a crossroads. AI could further exacerbate inequality. Or, properly harnessed and directed through government policies, it could contribute to a resumption of shared growth. Which will it be?

And don’t forget, the COVID-19 pandemic is still not over, with the risk of new variants and slow and ineffective rollout of the vaccines, especially in the global south. Moreover, this will not be the last pandemic. There are more to come. It has been the argument of Rob Wallace and other Marxist epidemiologists that pandemics have become more frequent because of the rapacious expansion into remote areas by fossil fuel, logging and agro firms. This has led to deadly pathogens getting into the food chain.

That theory has been now been supported by a new study suggesting that high pork prices in China after the recent swine flu epidemic there led to increased consumption of wild animals from markets. These animals were the conductors of the new pathogens. So industrial farming was the likely cause of COVID-19. “If more wildlife enters the human food chain, either through [individuals] hunting … or going to market and getting different meat sources. If that increases, it could just increase the contact opportunity,” said the author of the study, David Robertson, professor of viral genomics and bioinformatics at Glasgow University.

You’re just increasing the opportunity for the [Sars-CoV-2] virus to get into humans.

So maybe not just one year of the pandemic.