During the campaign for the presidency of Peru, the rural teacher and candidate Pedro Castillo, emphasized his identity with the thought of José Carlos Mariátegui. This served so that, in addition to being a ‘communist’, he was attacked as a ‘mariateguista’, a kind of ‘crime’, since, supposedly, that Peruvian intellectual had ‘inspired’ the Shining Path guerrilla, well known for its atrocities. Thus, under such guidelines, the country could hope not only to follow the path of Venezuela and Cuba, but also that of ‘violence.’ Castillo’s triumph has thrown all sectors that did not expect such a ‘coup’. And for now, with the support of the mainstream press, they have launched a fierce campaign to prevent Castillo from being proclaimed the new president of Peru, boycotting the results and even attempting a soft or strong coup d’état. But in Latin America it is already clear enough: the political and economic right wing is not willing to allow a democracy that provokes the triumph of other sectors, capable of questioning the power of dominant and exploiting elites.

In Ecuador the political scene has gone the other way. In recent elections for the presidency of the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities (CONAIE), Leonidas Iza (Kichwa of the Panzaleo people) triumphed, despite accusing voices of his ‘radicality’ which were raised. Immediately that victory awakened a paroxysm of opinionated stories in the commercial media, attacking Iza for being a ‘mariateguista’ and therefore linked to the spectre of potential ‘violence’.

Both in Peru and Ecuador, irrationality prevails on these issues and ignorance is imposed on those who make well-founded demands, with even a basic minimum of knowledge. Talking about Mariátegui without having read a syllable of his texts, or without having delved into the meaning and scope of his works, only has the purpose of deceiving society and frightening everyone with the very old fear of ‘communism’.

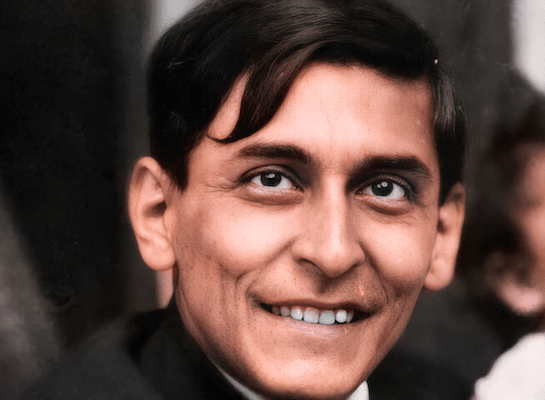

José Carlos Mariátegui (1894-1930) is one of the most prominent intellectuals (writer, journalist, essayist, researcher) in the history of Peru and a must-read author for those who study social sciences throughout Latin America. He is similarly followed in European and U.S. universities. His work is abundant (https://bit.ly/3dEG0jg) and there is an extensive documentary archive dedicated to his life (https://bit.ly/3hnTBfW). When he moved to Europe (1919) and specifically to Italy (where he married Anna Chiappe), he affirmed his Marxist training and on return to Peru (1923) he founded the Socialist Party (PSP, 1928) and the following year the Confederation of Workers. By then, all the communist parties were linked to the postulates of the Third International (1919) founded by V.I. Lenin; but, although Mariátegui recognized that organization, he was a pioneer in questioning all external ideological dependence, since Peruvian (and Latin American) socialism, he affirmed, should be ‘neither a copy, nor a copy, but a heroic creation’. This was a distinctive feature of his thinking that traditional left circles often repeated, although they were not always able to practice it. Mariátegui’s position caused him theoretical and political conflicts with the communist sectors; and, in fact, the Peruvian Communist Party (PCP, 1930), founded after Mariátegui’s death, became subject to the dictates of the Third International.

Mariátegui was not a ‘closed’ Marxist. He was convinced of the need for union with the democratic and progressive sectors, to achieve a cultural vanguard, and in this we see the influence of Antonio Gramsci (1891-1937), one of the founders of the Italian Communist Party (1921) and a man who theorized cultural hegemony. For this reason, from the Minerva publishing house, through the magazine ‘Claridad’ and, above all, through ‘Amauta’ (1926), the most important magazine that he founded, Mariátegui incorporated the most varied intelligentsia of the moment, including artists, workers, teachers and women writers, from the various Peruvian regions, in addition to maintaining contact with Latin American intellectuals and writing on multiple topics of literature, daily events or the political, social and economic life of Peru and the world.

Undoubtedly his most valuable work is ‘Seven Essays on the Interpretation of the Peruvian Reality’ (1928–https://bit.ly/3hpojFd), an in-depth study of the history of the country from a Marxist perspective, accompanied by other theoretical reflections. Here the essence of his thought on Indigenous-American socialism is concentrated. Above all, he demands the most rigorous investigation of reality; and for this reason he understands that the indigenous reality has been excluded in observations of a country where two-thirds are indigenous (‘Indians’). There cannot be a national political project that excludes them, yet that has happened, until today. In Peru it is impossible to think of a proletarian revolution that leaves aside the indigenous. In addition, in the cultural tradition and community life of the indigenous are the foundations for building socialism. Agrarian reform must be in their favour, while overcoming ‘feudalism’, sustained by internal gamonalism and the yanaconazgo system, that reform will have to be based on communal agrarian property, the basis of the new society. This frees the process from a passage through capitalism, a thesis Marx had also developed in the context of Russian communities (in his letters to Vera Zasúlich, published by Ryazanov in 1924) but which, at the time of Mariátegui, were not known in Latin American circles.

Mariátegui’s ‘indigenist’ theses, pioneering the Latin American Marxist perspective, earned him criticism and attacks from orthodox Marxists, who considered the indigenous issue simply as part of the class struggle and even a racial issue, arguments which Mariátegui constantly questioned, because he considered that this ‘Marxism’ did not understand the realities of Peru or Latin America.

Mariátegui never encouraged violence or armed struggle. A convinced Marxist, he trusted the party and the workers’ organization, along with the indigenous people, the popular strata and the intellectuals. However, the famous Peruvian did not manage to formulate a conception of the plurinational State, a perfectly valid contemporary approach which originated later in the same indigenous populations and organizations. Bolivia, first with President Evo Morales (2006-2019) and now with the presidency of Luis Arce Catacora (2020) is the most advanced Latin American country in the construction of a plurinational State and one that has shown undoubted social and institutional progress for the benefit of its broader population.

As in Bolivia, the indigenous populations of Peru and Ecuador have formulated proposals for a new society. Mariátegui’s thought can also assist their social and political positions, because ‘mariateguism’ is based on the option for democracy, peace, freedom and, without a doubt, socialism, proposed in favour of the oppressed classes. However this is an issue that the capitalist elites in Latin American neither understand nor want to accept. The problem of CONAIE and Pachakutik, in the Ecuadorian case, is one of their capacity to generate a political project of national scope, which does not focus on exclusively indigenous aspirations, but is rather integrated and connected with the broad interests of all the progressive and democratic left.

Juan J. Paz y Miño Cepeda, Ecuador, Monday, July 5, 2021. Translated by Tim Anderson from the original Spanish here: http://www.historiaypresente.com/la-demonizacion-de-mariategui/