Without acknowledgement of Brazil’s government for what it is–effectively a U.S.-backed military regime–no sense can be made of its recent past nor useful analysis of its coming elections. With attempts to force changes to the voting system, backed by threats that the 2022 elections will not take place at all, Brazil is entering phase three of its slow coup, and the consolidation of the military in power.

18.6% of 14,600 Brazilian government positions appointed under President Bolsonaro have been occupied by military personnel.

This figure is higher than the 1964-85 dictatorship-era peak.

There is needless semantic fog obscuring what Brazil’s government now is. Whilst the word “regime” is usually reserved in the anglosphere for officially enemies of the U.S. and allies, Brazil surely fits within objective definition; a military dominated, far-right authoritarian administration, which came to power by anti-democratic means–with coercion, threats, propaganda and abuse of the judicial system–which favours the interests of foreign capital, and which maintains itself through corruption, institutional confrontation, and violence.

Bolsonaro’s candidacy was democratic packaging for the long game of the military’s return to government. As they look to defend their position a year out from elections, the situation has escalated.

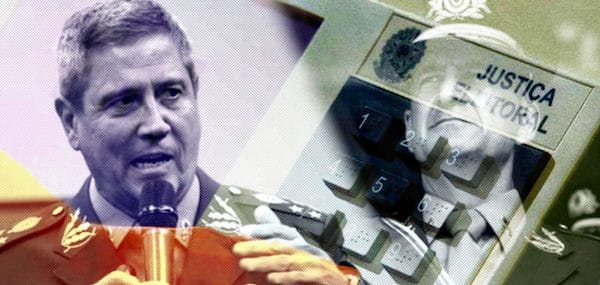

Bolsonaro’s former chief of staff and now defence minister, General Braga Netto is being called before the Supreme Court for his reported threat to head of Congress Artur Lira that if their desired change to the voting system–the introduction of a printed vote–was not implemented, that the 2022 elections would not go ahead.

Weeks prior, Braga Netto and other key Generals signed off on a letter threatening the Brazilian Senate over its investigation of former health minister, General Pazuello.

Now, Bolsonaro too is to be investigated by both the Electoral Court and the Supreme Court, for intentionally casting doubt on the country’s electoral integrity by spreading conspiracy theories about Brazil’s electronic voting system.

Both Braga Netto and Bolsonaro’s actions could constitute crimes. Bolsonaro already faces over 130 impeachment requests.

In a live broadcast on social media, which was reportedly the idea of Government Secretary General Luiz Eduardo Ramos, Bolsonaro made baseless claims of fraud at the 2014 election, blaming the voting machines, and calling supporters to the streets.

Using psychological operations techniques learned from WHINSEC, which have underpinned every stage of the long coup, the military’s ‘green and yellow nationalist’ supporters were again mobilised in support of this objective, which they depict as making voting “auditable” and “transparent”, under the false pretext that the current system is not.

Electoral Court President Barroso has warned that these changes would simply open the door to old school election fraud.

Bolsonaro looks like he will certainly need a means to contest the 2022 result; as things stand he is on course to lose heavily to Lula da Silva. The two would have faced eachother in 2018, had the former president not been jailed on since annulled charges to keep him out of the race, which happened with the judiciary acting under a succession of threats from the Armed Forces. Bolsonaro-allied, FBI-tutored prosecutors called Lula’s imprisonment “a gift from the CIA”.

It is extremely naive to expect the military to peacefully relinquish power after the decades it took to get back in government. Wishful thinking that Braga Netto and the other senior generals were adults in the room, a moderating force on Bolsonaro, or even that they would remove him, should have evaporated completely with admissions from General Villas Boas and Michel Temer about the military’s guiding hand throughout the 2013-16 coup and its second phase, the 2018 election campaign.

Bolsonaro was not a political accident that they reluctantly got behind, as some depicted. On the contrary, he was their candidate all along.

Now we are entering a third phase of Brazil’s long coup; a battle for the post 2022 scenario, with an effort to maintain the economic and foreign policy status quo under a more respectable face, meeting parallel neofascist attempts to consolidate power by any means.

Failure of any “third way” candidate to emerge that is capable of even competing with Lula at the polls may well have convinced both the military and the U.S. to stick with the name recognition they have, as Bolsonaro considers hikes to social security payments in election year to boost his trailing numbers.

Meanwhile US-trained, military-decorated Lava Jato judge, Sergio Moro, who helped put Bolsonaro in power by jailing Lula in 2018, is maintained as plan B or his potential successor. Moro recently returned from his new home in the United States to discuss his candidacy with the centre-right, Bolsonaro-allied Podemos party, and as was reported, even talk of a presidential ticket with current vice, General Mourão.

All of this is happening with the apparent blessing of the U.S. government. Visits in quick succession by both CIA director and National Security Advisor are tacit displays of support, expose the limits of environmental rhetoric over the Amazon, and pierce any remaining wishful thinking that Biden would be automatically opposed to Bolsonaro ideologically.

Brazilian governance in its current militarised state is far too useful to the U.S. strategically, and too good for business, to let go. After helping orchestrate much of the process that reduced Brazil to its desperate state, across Republican and Democrat administrations alike, it is extremely naive to expect the U.S. to change anything other than the superficial presentation of its Brazil relations.

CIA think tank CSIS is now promoting even closer ties, and the establishment of a “binational institution” to formalise the relationship between far-right, military-governed Brazil, and the United States.

Time is long overdue to drop any pretence about what Brazil faces. Depiction of Bolsonaro as the cartoon villain; a sole representative of what is actually a U.S.-aligned, long term military power project, is disingenuous. Anglophone media has for the most part adhered to the military and U.S. government’s coup-friendly master narratives throughout the process, and they continue to in this manner.

Similar refusal to acknowledge the gravity of what Brazil faces is how the 2016 coup against Dilma Rousseff’s government was placed in inverted commas and reduced to a matter of opinion, how Lula’s political persecution was depicted as legitimate, and how a neofascist military backed candidate was reduced to simply a “conservative”, whom moderate voters and foreign investors alike could be comfortable with.

Without recognition of Brazil’s government for what it is–yes, a U.S.-backed military regime–no sense can be made of its recent past, nor its troubling near future.