As rightist repression against jailed worker revolutionaries spread across Europe in the 1920s, the Communist International initiated a united-front international defense effort, whose influence soon extended far beyond the limits of the Communist movement.

The initiative came from Polish Communists seeking to aid compatriots jailed or forced into exile in the Soviet republic. Initially, the goal was to raise funds within Soviet Russia; the prestigious Society of Old Bolsheviks offered to help these efforts.

In December 1922, the Comintern’s Fourth Congress adopted an appeal to all member parties to: “Take the initiative … to organise material and moral assistance to vanguard fighters for the cause of communism who are locked in prison, forced into exile, or for any reason excluded against their will from our fighting ranks.” (See text of resolution, below.) The campaign bore the name International Organization for Aid to Revolutionaries and was usually referred to as MOPR (its Russian acronym) or International Red Aid.

The first major operation of the new movement was launched in October 1923 in aid of victims of repression in Bulgaria. The first international conference took place on 14–16 July 1924, with 108 delegates, two-thirds from outside the Soviet Union.1 Its purpose expanded from material aid to embrace international protest and political advocacy on behalf of prisoners.

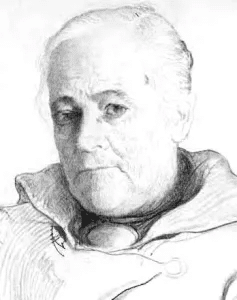

Although structurally autonomous, International Red Aid’s close partnership with the Comintern was assured by the presence of Communists as a majority of its governing body. Julian Marchlewski served as its initial president (1922–25), followed by Clara Zetkin (1925–27) and Elena Stasova (1927–37).

In 1925, International Red Aid claimed five million adherents, mostly in the Soviet Union but extending, in many capitalist countries, far beyond the membership of the Communist parties.

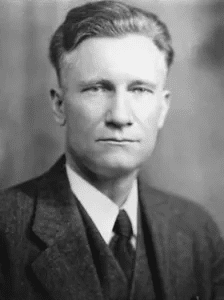

A graphic portrayal of International Red Aid in action can be found in the writings of James P. Cannon, who from 1925 to 1928 headed its United States affiliate, International Labor Defense (ILD), as well as in the biography of Cannon by Bryan Palmer.2

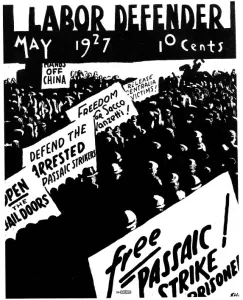

According to Cannon, the ILD’s monthly publication, Labor Defender, had a circulation exceeding that of the three main Communist Party publications put together. By the end of 1926, ILD had 20,000 direct and 75,000 affiliated members.3

Palmer terms the ILD the “most quintessentially united front activity” in the U.S. during the 1920s. It was built on unity with the anarchists and IWW militants who accounted for the majority of 128 U.S. political prisoners.

Cannon mapped out plans for the IWD in a 1925 discussion in Moscow with exiled IWW leader Big Bill Haywood. “Deeply concerned about the persecution of workers in America,” Cannon later recalled, Haywood “wanted to have something done for the almost forgotten men lying in jail all over the country…. They were not criminals at all, but strike leaders, organizers, agitators, dissenters–our own kind of people. Not one of them was a member of the Communist Party! But the ILD defended and helped them all.”4

Survey of Comintern Auxiliary Organizations: Contents

- Introduction

- Red International of Labour Unions (RILU or Profintern)

- Communist Youth International

- Communist Women’s Movement

- International Workers’ Relief (MRP)

- International Red Aid (MOPR)

- Communist Cooperatives

- Red Sport International (Sportintern)

- Peasant International (Krestintern)

Cannon adds that ILD “created a fund so that $5 was sent every month” to each of the class war prisoners, plus a special Christmas payment to their families. A full, audited financial report on ILD receipts and disbursements appeared in each issue of Labor Defender.

Cannon and other ILD activists paid frequent personal visits to the prisoners in their care, and often reported on them in the Labor Defender. He recalled an apt comment by Eugene Barnett, one of the ”Centralia” prisoners, jailed as part of a cover-up of a rightist mob attack on a workers’ assembly.

We are part of the price paid for better conditions for the lumber workers.5

The ILD’s greatest campaign was for the victimized anarchists Nicolo Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, framed up and convicted of murder in a robbery. International Red Aid launched an international campaign to save them from execution, which included demonstrations in the tens of thousands. The two defendants were executed regardless, but the Sacco-Vanzetti case remained a defining experience in the radicalization of a generation.

Cannon was forced out of International Red Aid when he broke with Stalinism in 1928, as were the co-thinkers of Clara Zetkin in Germany.

Many years later, Cannon compared such sectarian behavior with the prior record of ILD and–by extension–International Red Aid:

The principle of the International Labor Defense, which made it so popular and so dear to the militants, was nonpartisan defense without political discrimination. The principle was solidarity.6

Fourth World Congress Resolution on International Red Aid

Resolution on Assistance for Vanguard Fighters of the Communist Movement7

The Comintern recognises the need to organise international material assistance for vanguard fighters for communism–whether or not they belong to the party–who are held prisoner by the reactionary governments of various countries. This initiative is placed on the agenda by the sympathy of the broad masses for the cause of struggling to eliminate the old, outlived forms of social life and replacing them by new forms that represent the beginning of communism. The Comintern therefore addresses the following appeal to all Communist parties:

1.) Take the initiative–or support it, if it has already been taken–to organise material and moral assistance to vanguard fighters for the cause of communism who are locked in prison, forced into exile, or for any reason excluded against their will from our fighting ranks.

2.) The Communists of Soviet Russia must take a very special initiative here. Such organisations to support victims of political struggle for communism can take on large scope as measures toward uniting internationally all those who sympathise with the cause of communism.

Notes:

- ↩. E.H. Carr, Socialism in One Country, Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1972, p. 987.

- ↩. James P. Cannon, The First Ten Years of American Communism, New York: Pathfinder, 1972, pp. 21–103.

Cannon, Notebook of an Agitator, New York: Pathfinder, 1993, pp. 21–103.

Bryan D. Palmer, James P. Cannon and the Origins of the American Revolutionary Left, 1890–1928, Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2007, pp. 261–73. - ↩. Palmer, James P. Cannon, p. 269.

- ↩. Cannon, First Ten Years, p. 162.

- ↩. Cannon, Notebook, p. 88.

- ↩. Cannon, First Ten Years, p. 164.

- ↩. See John Riddell, ed., Toward the United Front: Proceedings of the Fourth Congress of the Communist International, 1922, Brill/Haymarket Books, Leiden/Chicago, 2011, pp. 960–1.