DESPITE THE REDACTIONS, the pseudonyms, and the thousands of unreleased pages, the Senate intelligence committee’s report into post-9/11 CIA torture–that is, the executive summary available to the public–is the most robust oversight ever conducted of any part of the War on Terror. The committee typically defends the agencies and activities it nominally oversees; remarkably, the torture investigation revealed the gruesome realities inside the CIA’s black sites. It demonstrated, with precision and rigor, how the CIA constructed a Big Lie, called “Enhanced Interrogation,” around its barbarism.

But the committee’s lead investigator says that he could only investigate two of the three components of the torture program. The third is lost to history.

THE CIA CALLED THE PROGRAM RDI, for Renditions, Detentions and Interrogations. “Renditions” are outsourced torture: the CIA abducts someone and sends them to be abused either by their home country’s security apparatus; or, in the “extraordinary rendition” variant, by a third country’s security apparatus. “Detentions” were the maintenance, logistics and direct operations of the black sites where the CIA, not an allied intelligence service, imprisoned people. “Interrogations” were the torture the CIA inflicted.

Renditions were the kernel of the program. They were the only aspect of CIA torture in operation on 9/11. The entity within the CIA Counterterrorism Center that conducted it, the Renditions Group, expanded after 9/11 to become the RDI Group, or “RDG.” One of the people involved in the Renditions Group from inception, Mike Scheuer, explained many years ago in an underappreciated video, “After 9/11, the CIA was the only game in town. The Bush White House pushed on the CIA to accelerate the rendition program.” (Scheuer has been on a journey.)

Yet we know vastly more about the D and the I than we know about the R. The Senate’s investigation solely concerned the CIA’s detentions and interrogations. Over the six years of the investigation, the CIA fought aggressively to restrict even that constrained mandate. It was not going to allow Senate investigators to expand their remit, according to Daniel J. Jones, the lead investigator. “Everything was a heavy lift,” Jones remembers.

And even if the agency somehow had allowed him to investigate renditions, Jones’ experience of digging through deliberately confusing and incomplete records that the CIA provided–and sometimes subsequently disappeared–leads him to the conclusion that the agency’s own renditions records are likely far from extensive.

“The [CIA’s detention and interrogation] records in 2002 are detailed. As the ‘DI’ program went on, we saw less and less robust record-keeping,” Jones recalls.

One could imagine that also applied to rendition.

All three components of the program were tied together, and so occasionally Jones saw glimpses; suggestions and clues to what rendition was. But not only was rendition beyond the scope of his investigation, he already had to contend with the maddening and painstaking work of figuring out who was and was not in CIA custody, then figuring out how meaningful such distinctions were when it came both to internal classifications and the actual treatment of human beings. It was arduous.

Officially speaking, the Senate was able to tally at least 119 people whom the CIA held in the black sites during their 2002-2008 existence. “There’s a back-and-forth we had with the agency on who was a CIA detainee and who wasn’t. The committee, to arrive at 119, is extremely conservative. Everyone who was involved in this investigation believes there was more than 119 CIA detainees,” Jones explained.

“If the CIA doesn’t know how many people were in its own custody, it’s very unlikely there’s any record-keeping of people who were merely transients”–that is, briefly in CIA custody before being whisked to a partner intelligence service–“and those who weren’t in their custody. …Tenet and every other [CIA] director said [the torture program] was the CIA’s central counterterrorism program at the time. Because it was a central program–and incredibly sensitive–it would be reasonable to think the CIA would maintain a robust classified record,” he continued.

If, in fact, the ‘DI’ part was viewed as the central component of the War on Terror by the CIA, there’s no reason to believe they would hold better records with the rendition program.

TWO BROAD FACTS ABOUT CIA TORTURE make Jones’s supposition especially compelling.

First, the only reason the Senate intelligence committee investigated at all is that two leading figures inside the program, Jose Rodriguez and Gina Haspel, destroyed videotapes of the torture of two men inside the first post-9/11 black site–something that also sparked a criminal investigation. Once the Senate learned about the destruction of those tapes from The New York Times, rather than from the CIA, the committee could no longer credibly refuse to open an investigation of its own.

Second, in most major speeches and testimony, CIA directors George Tenet, Porter Goss, and Michael Hayden repeatedly emphasized that their War on Terror is an international team sport. They did this so often that journalists rarely bothered quoting it; it seemed like boilerplate. It was often self-serving, as when they cited the importance of cooperation with allied intelligence services as a reason to never disclose what that cooperation did. But they’re correct that reliance on various Mukhabarats makes their war viable. “I cannot overstate how vital these relationships are to our overall effort,” Hayden said in one typical September 2007 appearance.

The absence of renditions records, even to the Senate torture report, is no longer exactly news. I reported it in 2016 in this 20,000-plus-word, three-part series for The Guardian. But what has bothered me ever since is how little attention and care that absence has ever received. In the wake of our recent Forever Wars piece about naming the dead, I’ve been thinking about that more and more–the enormous gap in our historical knowledge of renditions; the likelihood that if the Senate torture report couldn’t go there, then we’re probably not going to fill those gaps; and the fact that pretty much no one gives a shit.

The awful conclusion is that disappearances work.

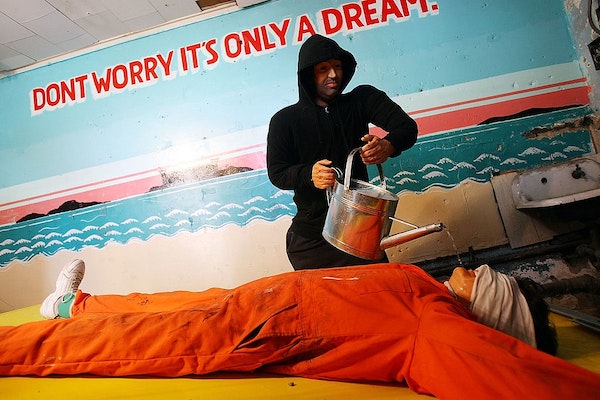

WE KNOW SOME THINGS ABOUT RENDITIONS. In particular, we know that the CIA took bondage nudes of bound prisoners at the point of transferring them. That was documentation of the renditions–presumably made to provide proof that someone who might ultimately die in a foreign torture chamber was alive when the CIA had them.

Human Rights Watch, in 2008, was able to document 14 people the CIA rendered to the Jordanians. One of them, Abu Hamza al-Tabuki, recalled: “from the first day, they began to interrogate me using the methods of terror and fear, torture and beating, insults and verbal abuse, and threatening to expose my private parts and rape me. I was repeatedly beaten, and insulted, along with my parents and family.” Those familiar with the history of torture, particularly in a context of war, will note how present sexual torture is within it.

When the U.S. helped overthrow Moammar Qaddafi in 2011, it inadvertently led to the publication of the files locked in the offices of Qaddafi’s internal-security apparatus. That ended up accidentally exposing what CIA-Libya cooperation looked like in practice. It’s really not a pleasant read. Neither is the messy history of the rendition of Abu Omar, whom the CIA abducted in Milan after Italy had granted him asylum.

In my 2016 Guardian piece, I reported that renditions were the “largest” part of RDI. Jones reminds me, helpfully, that “we don’t really actually know that.”

Fair enough. I was using a European Parliament investigation from 2007 that reported:

at least 1,245 flights operated by the CIA flew into European airspace or stopped over at European airports between the end of 2001 and the end of 2005, to which should be added an unspecified number of military flights for the same purpose;… on one hand, there may have been more CIA flights than those confirmed by the investigations carried out by the Temporary Committee, while, on the other, not all those flights have been used for extraordinary rendition.

Note that last line. Note how the EU acknowledges the limits of its investigative visibility into European complicity. The EU investigators are able to document over 1,200 CIA flights to Europe over four years. They can’t say each flight was a renditions ferry, or that each flight equals a person rendered. They can say they are unable to answer the question, and as a fallback, offer their best evidence as a proxy for the scale of a program whose surface they can barely scratch, thanks to the obstinacy of several governments.

Hayden, in 2007, weaponized that uncertainty to discredit the EU. “The suggestion that even a substantial number of those 1,245 flights were carrying detainees is frankly absurd on its face,” he scoffed.

Except it’s not absurd at all. It is true that Hayden had exclusive access to whatever remained of the CIA record, so he could make assertions about the CIA torture program being “designed only for the most dangerous terrorists and those believed to have the most valuable information, such as knowledge of planned attacks” from a position of authority.

Unfortunately for Hayden, Scheuer, who said he “ran renditions” when he was at the Counterterrorism Center, accidentally contradicted him in 2008.

“Under Mr. Clinton we had focused on very senior al-Qaeda people,” Scheuer (who didn’t respond to a message seeking comment) recalled at an event at Berkeley that year. After 9/11, he told the audience, “the bar went down a little bit, and we began to pick other people up.” (This is around minute 32:30 in this video.)

Defenders of rendition, Hayden included, tend to describe rendition as lawful, complete with guarantees from other nations of humane treatment. Scheuer is a rare CIA official who acknowledges on record that that’s bullshit. “Under Mr. Clinton, we were to take them off the street and arrange for them to be returned to a government that wanted them for a judicial process,” he said at that event.

We went back to the White House and said, “This was what we planned to do, do you want us to do it?” Yes, was the answer. “Well, we’re going to take them to countries where they’re wanted, but your State Department, every year, is going to say ‘that country is a human rights abuser,’ or its judicial processes are not what we want them to be.” And everybody kind of puckered up and said, “Ooh, that may be a problem. Can you get these countries to say ‘We will treat these rendered people according to our own laws?’” And we said, “Yeah, we’re pretty sure that country X will treat them according [to their own laws]–that won’t get you off the hook!” But that’s as far as it went. Now, President Clinton and [national security adviser Sandy] Berger said that they insisted on guarantees that these prisoners would be treated according to American standards or international law. Now, I was there. I ran the operations. That was never a requirement that I knew of. That’s entirely a kind of after-the-fact defense of what was done.

Hayden has a track record of lying. When Jones was able to examine the records of the CIA’s detentions and interrogations, he saw just how heavily Hayden and others in the CIA manipulated the truth. An entire annex of the Senate intelligence report debunks a fusillade of lies Hayden told about CIA torture in just one day of testimony. (Appendix 3, starting on page 462 of the report.) And that’s not the end of it: see Reign of Terror, out on Tuesday. (Also, I have a story about Hayden showing up at one of my band’s shows; I might write about that for subscribers, so please do subscribe.)

Scroll up in this piece to the quote from Jones about how there’s a “back-and-forth” over who the agency counts as detainees, prompting the Senate to act conservatively in tallying 119 men at the black sites. Hayden, in 2007, claimed the number of black-site prisoners was “fewer than 100.” All this is particularly glaring when reviewing Hayden’s assertion, in the same speech, that “the number of renditions is actually even a smaller number, mid-range two figures.”

WHAT WE LACK, and what we will likely always lack, is a systemic understanding of the renditions, extraordinary and (sighs) “ordinary.” The Senate intelligence committee report emerged from a unique opportunity and set of historical circumstances. Neither will come again. Jones performed an extraordinary service for history. I don’t write any of this to fault him for being unable to unearth the rendition program–no one outside of the Church and Pike committees has done more to force real transparency out of the CIA.

“We had two options in a world of limited resources: to attempt to totally detail all the renditions; or to detail the ‘D and I’ in U.S. custody,” Jones said. “It’s still the right call, but it makes the false assumption that Congress can only have the most minimal of investigative resources. In essence, we’ve decided to live in this world of limited oversight.” Damn. Sit with that quote a moment.

Jones is pointing to a consequence-free obliteration of truth. The mark on the victim’s body is torture’s true measurement, especially when we believe that every human being has inherent worth and dignity. The official denial that the mark was made, aggregated across an unknown number of people, is no longer a crime against them alone but a crime against history. One of the people directly involved in both the mark and the denial, after both were known, rose to become CIA director, to bipartisan acclaim. One of her boosters is, right now, the Director of National Intelligence. Another chairs the Senate intelligence committee.

“The oversight mechanisms and the executive branch have allowed both inappropriate and illegal behavior to happen without consequence,” said Jones.

There’s never any accountability. There is no leash. It’s just unclipped. In such a lax oversight environment, why would they think they need records?