In the early weeks and months of the pandemic, tipped restaurant workers, like other low-wage workers across the country, faced both the sudden disappearance of work and the involuntary “essential worker” designation. Those returning to their workplaces braved dangerous, even deadly, conditions. Many actually found themselves working the same jobs for significantly lower wages, as customers were less inclined toward generosity or the pandemic conditions made impossible the tip-earning work of interactive service.

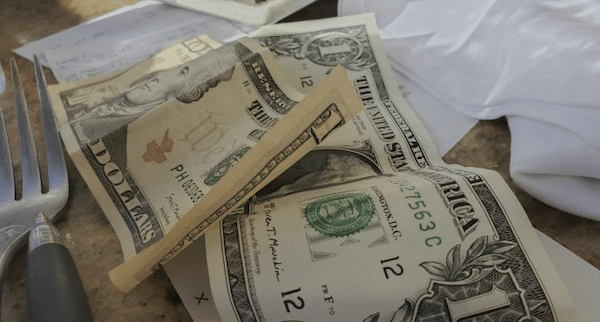

It is a situation that underscores the precarious situation of tipped workers, whose income depends largely on the whims of customers. Employers have only a minimal financial obligation to these workers—well below the minimum wage in most of the country, and federally just $2.13 per hour. While some states have eliminated this lower wage, others have made moves in that direction only to cave to an onslaught of resistance. And the restaurant industry has fought hard to retain this massive subsidy, just as it fought for wage code exemptions in the early 20th century and to freeze the tipped wage at $2.13 back in 1996. It’s backed an astroturfed “Save Our Tips” campaign to counter the anti-tipped wage One Fair Wage project.

That said, the tipped wage issue doesn’t cohere neatly to a case of workers versus unscrupulous employers. Workers themselves have campaigned and argued to keep the subminimum wage in op-eds and public hearings. What explains the strange circumstance of workers rejecting a higher wage?

At work in the restaurant

In 2019 I started a workplace ethnography and interview-based project on the tipped subminimum wage and workers’ perspectives on it. I traced also its origins—from an informal practice exploited by employers who targeted formerly enslaved workers to a legally codified feature of contemporary service work. A situation that would seem preposterous in most other contexts—working without knowing how much, or even if, one will be paid, and without any right to demand payment—is today entirely normalized in tipped occupations.

I worked in the front-of-house at a large multinational chain restaurant, and there this dual wage system had profound implications. Tipped workers became skilled self-managers and self-exploiters. One server described the “rush” of a good night, which left her “feeling…individually capable as this mercenary person.” My coworkers and interviewees likewise professed pride in their entrepreneurial canniness—a boon to management, whose aims largely accord with those efforts of tip earning.

This may explain why several servers told me they avoided working in restaurants where tips were pooled and shared. “I’m me. I’m selling my personality,” said one. Another told me that she saw tip sharing as blatantly unfair: “I have regulars that come back to see me because I’m a successful person.”

My coworker described the repetitive stress dreams that followed her shifts, and I asked her what provoked these nightmares. “The customers,” she said. “I’m not worried about the managers. They don’t do anything. They don’t care.” Since the near-entirety of workers’ earnings came directly from customers’ tips, customers in turn absorbed the near-entirety of workers’ attention on the floor. Management lurked in the background, sometimes menacing but largely superfluous.

This attitude is not simply misapprehension on the part of the server, but a direct consequence of the two-tier wage system, which makes customers the unwitting disbursers of a legal wage and obscures workers’ objective relationship to employers. This wage relation conditions workers to look for their livings to customers and their own ingenuity, not to the boss who pays a wage so insignificant that one server described it as “just extra money,” which he spent buying Gatorade at the gas station on his way home.

The trouble with the customer as wage provider is that workers have no employment contract with customers. Customers might not tip at all, and even if they do, studies show that tipping reinforces social inequalities, as nothing prevents customers from calculating tips adherent to their own biases. In the interest of making rent, workers might feel compelled to tolerate discriminatory, or just plain creepy, behavior. Servers I spoke to had ample firsthand experience of prejudicial treatment, whether they attributed it to race, gender, sexuality, or some other marker of identity. The precariousness of tipped income is a definitively structural feature, but one that the individual worker experiences as deeply personal.

Two-employer problem

The tipped wage creates something I’ve called a two-employer problem. It sets up the customer as unregulated, phantom employer, and provider of the bulk of a worker’s earnings. Yet between workers and customers, unlike between workers and employers, there exists no terrain of struggle over the (morally- and historically-determined) value of that wage. The tipped worker has also the strange experience of first selling their labor-power to their employer, at a rate both parties agree is well below its value, then attempting its resale to the customer, this time advancing its use-value without guarantee of payment.

There is precedent for drawing a relationship between nonstandard wage structures and the consciousness that workers do or do not develop on the shop floor. Late in the first volume of Capital, Marx turns to the case of the piece-wage, which workers earn not by the hour but at a set rate per completed piece. Although the piece-wage did not alter the objective relations of production (and was, Marx points out, really just a reconfigured form of the time-wage), it did a great deal to shape the way that workers undertook and understood their work. It compelled them to work harder and faster, for longer hours, obviating much of the need for direct management. Marx even calls the piece-wage “the form of wages most in harmony with the capitalist mode of production.”

The consequences of the piece-wage strikingly resemble those of the tipped wage, and workers organizing service industry unions in the early 20th century saw these dangers in the practice of tipping. Many (although not all) unions fought both the practice and its institutionalization in formal wage codes on the grounds that tip-earning necessitated workers’ participation in a servile—even feudal—relationship to customers and shaped an individualizing labor process that encouraged overwork and disinclined workers to organize together.

Unfortunately, we may be living in that worst case scenario foreseen by service industry workers a century ago. Tipping and the tipped wage did become firmly entrenched, and today unionization rates in the restaurant industry are some of the lowest in the nation. Tipped workers may have many reasons for opposing industry-wide wage increases. (One career server I interviewed told me he simply feared change in an industry, and broader context, already so precarious.) But as the above accounts suggest, the wage itself may well pose an obstacle to the organizing that could most effectively bring it to an end.

In the wake of pandemic shutdowns, low wages and high risk have prompted many workers to exit the restaurant industry altogether, but of course not everyone has that option. Eliminating the tipped wage won’t immediately rewrite the relations in production of an entire industry. Nor will it shake a deep, and deeply American, ideological commitment to entrepreneurial individualism. But it may be a necessary first step toward improving the conditions of work in an industry still mired in its sordid past.

Hanna Goldberg is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Sociology at the CUNY Graduate Center.a