Last week, 420 U.S. sailors and 200 Marines were deployed to Haiti, ostensibly to help provide humanitarian relief to victims of the Aug. 14, 2021 earthquake that struck Haiti’s southern peninsula. It marks the sixth official U.S. deployment of troops in Haiti since Dec. 17, 1914, when U.S. Marines first landed to unilaterally take, despite Haitian government indignation, $500,000 in gold from the vaults of the National Bank of the Republic of Haiti (BNRH), the nation’s central bank at the time. (One must specify “official” because U.S. troops – often Haitian-Americans–have been covertly deployed in Haiti on several occasions over at least the past three decades.) Subsequent U.S. military interventions would occur on Jul. 28, 1915, Sep. 19, 1994, Feb. 29, 2004, and Jan. 14, 2010.

These U.S. invasions, always justified by a political crisis or natural disaster, are just the muscled manifestation of an “invisible hand:” that of finance capital.

The penetration of U.S. finance capital into Haiti and the Caribbean, displacing European finance capital, is laid out in great detail by Peter James Hudson, an Associate Professor of African American Studies and History at UCLA, in his 2017 book “Bankers and Empire: How Wall Street Colonized the Caribbean” (University of Chicago Press).

Over the next three weeks, we will publish extended extracts (without the footnotes) from “Bankers and Empire” to edify our readers as to how Haiti became so beholden to and dominated by Washington and Wall Street.

– Kim Ives

Introduction: Dark Finance

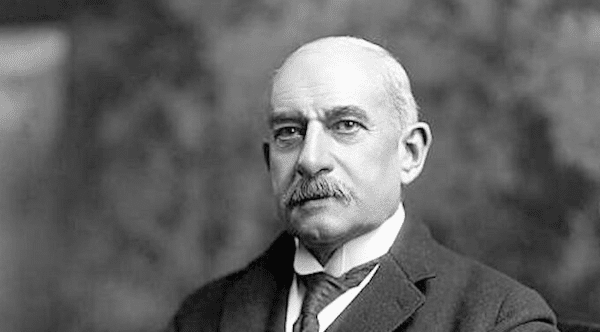

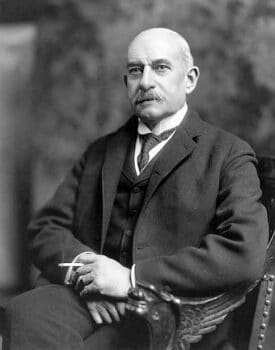

James Stillman, City Bank’s president from 1891 to 1909, was one of the architects of the bank’s imperial expansion.

When James Stillman, president of the National City Bank of New York, began searching for a space to replace the bank’s cramped and old-fashioned headquarters at 52 Wall Street, he sought a building that could evoke the City Bank’s transformation from an early 19th-century merchant bank into one of the most powerful financial institutions in the United States. Stillman wanted a building that signified the City Bank’s new identity while recalling the old, a building that could project strength, stability, and permanence while embodying his almost metaphysical ambitions for the bank’s expansion and growth. Instead of constructing a new edifice from the ground up, Stillman decided to purchase and renovate the old U.S. Customs House at 55 Wall Street.

There were some reservations concerning the new building. Frank A. Vanderlip, who replaced Stillman as City Bank president three weeks after the opening …, had wanted a large, modern structure. He anticipated that the fast-growing bank would soon face a crisis of office space, and had gone as far as having plans drafted for a multistory tower.

But hidden behind 55 Wall Street’s façade of neoclassicism was another imperial enterprise: an enterprise of banking, finance, and empire whose ambitions and expansions were braided through the U.S. colonial and neocolonial projects of the early 20th century. While the City Bank was undergoing a transition from 19th-century merchant bank to 20th-century commercial and industrial financier, it was also remaking itself as an international financial institution. Where it was once jockeying for business and influence among the brokers, merchants, and commission agents of old New York, the City Bank was now muscling its way to a seat at the table of international finance alongside the imperial banking houses of London, Paris, and Berlin. And where it once served the financial needs of a fast-growing domestic economy, it was increasingly involved with the banking, trade finance, and debt issuance of the Caribbean, Latin America, and Asia.

By the time 55 Wall Street’s renovations were complete, Stillman and Vanderlip were recasting their institution as an imperial bank. The City Bank’s history began to be written overseas, and it increasingly grappled with the conundrums of law and regulation governing international commerce, banking, and finance, as well with the questions of racism and militarism underwriting U.S. imperialism and finance capitalism.

The early history of U.S. imperial banking and the internationalization of Wall Street began alongside the project of U.S. colonial expansion at the turn of the 19th century and ended amid the financial and economic crises of the 1930s. It was fueled by the capital accumulations reaped from the industrial development, corporate consolidation, and economic expansion that followed the grim history of territorial dispossession that marked the settling of the U.S. West. New York City was its engine. New York’s bankers reaped the rewards of this growth as both the financiers of industrialization and as the representatives of a banker’s bank serving regional financial institutions and the federal government. Buoyed by this newfound wealth, New York City’s financial institutions began to look overseas, searching for outlets for their swelling accumulations of unproductive capital. They also sought to consolidate Wall Street’s international position in finance, trade, and commerce. They viewed the organization of an imperial banking system as a critical component in the rise of New York and the westward traverse of the “star of financial supremacy,” as imperial theorist and financial reformer Charles A. Conant referred to it, from Europe to the United States.

The U.S. government encouraged and supported the internationalization of U.S. banking. The War and State departments required fiscal agencies to support the infrastructure of U.S. colonialism, and financial institutions were an important conduit of colonial policy and financial and commercial diplomacy. Bankers, however, needed little prodding to move overseas and the relations between Wall Street and Washington were contested and contentious.

The City Bank was at the center of the history of banking internationalization and imperialism. A federally chartered commercial bank, it emerged as the largest and the most important imperial financier in the United States. Under Stillman and Vanderlip, the City Bank adopted an aggressive, entrepreneurial, and activist strategy for expansion and growth.

The City Bank also made the Caribbean the centerpiece of the largest foreign branch bank system of any U.S. financial institution as it pushed for a share in a market long dominated by Europe and Canada. As part of its efforts of internationalization and in the attempts to create an institution for imperial accumulation, the City Bank hammered away at the banking regulations shackling its activities and pushed for regulatory reform. And in its encounters with the peoples, nations, and colonies of the Caribbean and Latin America, it participated in the creation, replication, and reordering of Caribbean economies on racial lines while helping to reproduce the racist imaginaries and cultures in which finance capital was embedded and through which bankers functioned.

The disordered global financial and economic conditions unleashed by the First World War accelerated the internationalization of Wall Street and intensified the relationship between banking, bankers, and imperialism. More than any other institution, the City Bank under Vanderlip took advantage of the opportunities provided by the war and ran with the new banking legislation of the Federal Reserve Act (1913), the federal legislation that modernized the U.S. financial system and created the legal platform for foreign branch and commercial expansion.

The era of internationalization ended in the 1930s. Black Friday and the stock market crash of 1929 led to a crisis of finance capitalism. The crisis sparked a wave of both antibanking and anti-imperialist sentiment in the United States and the Caribbean. It drew attention to the usurious interest rates and suffocating fiscal conditions imposed by bankers on sovereign nations, the strong personal and financial ties between Wall Street and despotic and dictatorial regimes in the Caribbean, the ongoing support for U.S. military occupation by finance capital, and the virtual control of Caribbean industry and agriculture by banking houses.

The Federal Reserve Act also contained a number of provisions crucial to the expansion of U.S. banking and markets abroad. It created an international system of discount that facilitated the financing of international trade by national banking associations, and provided for the establishment of foreign branch banks.

As bankers like James Stillman and Frank A. Vanderlip and lawyers like William Nelson Cromwell and John Sterling slouched in their mahogany-paneled offices and ersatz renaissance parlors–sipping scotch amid overstuffed furniture, marble statues, and velvet curtains suffused by the smoke of Cuban cigars–and outlined the notional visions of imperial finance, on the ground in the Caribbean and Latin America, another set of white men were turning the financial abstractions into monetary reality and performing the dirty labors of international banking and empire. These men, individuals like the City Bank’s Roger L. Farnham, John H. Allen, and Joseph H. Durrell, have dwelt in the shadows of the larger-than-life robber barons and “wizards” of modern finance who have dominated the lore and historiography of U.S. banking. These unheralded and lesser-known figures were curious individuals. With their knowledge of foreign languages and extensive travel experience, they were cosmopolitan in a way most Americans of the time were not–even as they were still shaped by many of the racial and cultural prejudices of their compatriots. Always white, always male, half frontiersman, half accountant, more hardened than the gentlemanly capitalists of the City of London, less knowing than the economic hit-men of popular literature, they were rogue bankers who entered the profession with little formal experience and often with no formal training. Some began as journalists and reporters. Others started as the managers of country banks on the U.S. frontiers. Most eventually drifted to New York City and on to the Caribbean and Latin America and back again, finding employment in the U.S. imperial banks operating throughout the region.

Allen aided the bank’s expansion into Cuba and Argentina and was the manager of the City Bank–controlled Banque Nationale de la République d’Haiti in the 1910s. He is perhaps best known for his 1930 article recounting William Jennings Bryan’s decision making in the lead-up to the landing of U.S. Marines in Haiti in 1915. In the article, Allen recounts a 1912 briefing Bryan on Haiti’s history and politics. After listening carefully to Allen’s comments, Bryan responded,

Dear me, think of it! Niggers speaking French.

Years earlier, in the City Bank’s foreign trade journal The Americas, Allen evoked a picture of Haiti that would have been recognizable to white U.S. audiences but for its tropical difference. Allen asserted that “cock-fighting and card playing are the [Haitian] national pastimes, and these, together with a supply of Haitian rum, are all that is necessary for a Haitian citizen’s perfect day.” He claimed that during his visits to Haiti he found that “humorous incidents were of almost daily occurrences.” For Allen, such incidents “showed the naivete and also the restricted mentality of the [Haitian] people, which latter was plainly noticeable even among the more highly educated.”

To be continued