Adam Mayer celebrates a new volume on the Russian revolutionary Vladimir Ilyich Lenin. Lenin150 (Samizdat) has a sheer diversity that takes one’s breath away. Authors young and old, queer and old-style Marxist-Leninist, women and men write about Lenin’s work, history and legacy in an anthology that also includes many African and Black voices. Mayer argues that this rich collection proves that Leninism is alive and well.

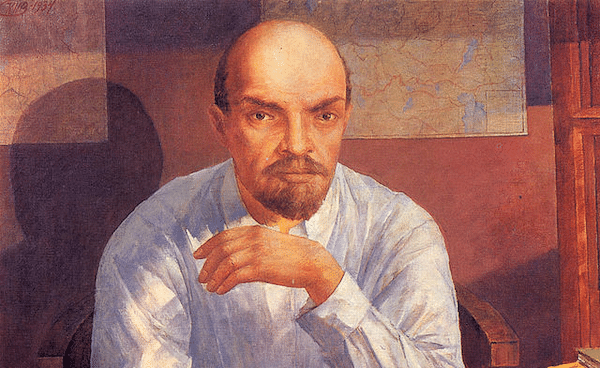

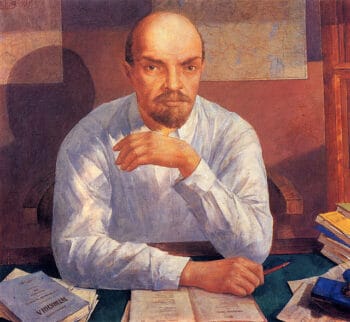

Hjalmar Jorge Joffre-Eichhorn, the main editor of this magnificent edited volume of socialist theory, history and literary art (especially poetry), as well as a collection of Lenin visuals presented via art photography and a number of other mediums, has created a celebratory tome to mark the 150th birthday of Lenin. The picture presented in the volume is one of the Leninists’ Lenin (with partial exceptions), but he and his co-editors certainly did not aim at conveying a composite historical account that would include every possible voice from Russian Orthodox priests’ through neoliberal pundits’ and new right fascists’, to the Vatican’s or the Taliban’s conception of Lenin and his historical role. Rather, the work comes together as a well composed symphony with magnificently presented, interwoven themes: with lots of humor, nuance, drama and self-awareness, but also (to use the editor’s favourite term), lots of real, unadulterated, pure joy.

In some cases, themes disappear and re-appear, as when one of our subculture’s favourite taboos, the fact that ‘state socialism’ as an economic system was designed by Yevgeni Preobrazhensky as late as 1926 is mentioned in one of the multiple Introductions (p.6) and then again on p. 229–but how delightful, how relevant, how deep this discussion on this much forgotten topic here is! Matthew T. Huber’s chapter, for example, goes into the highly controversial topic of the concept’s provenance. Preobrazhensky was initially allied to Trotsky within the Left Opposition and Stalin, after ‘eliminating’ the entire Left Opposition in the 1930s, including Preobrazhensky, unleashed the most ruthless industrialization by dispossessing the peasantry–all in the name of ‘state socialism’.

Such themes, rich and sometimes surprising as in possible connections between Aleister Crowley and Lenin (in Oxana Timofeeva’s intriuguing chapter, ‘What Lenin Teaches Us About Witchcraft’), appear and re-appear in visual rhythms not so much as in a kaleidoscope than as in fireworks–of the most spectacular kind. (And yes, Joffre includes a People’s Republic of China scholar on Lenin, Wang Hui, as well as a Western Marxist theologian (!) who works in China).

Joffre’s Lenin is a decolonial Lenin first and foremost. He is called a “non-White man” (p. xviii) and this is as well, given Lenin’s Tatar features and Russian, Jewish, German/Swedish and also Kalmyk ancestry, as well as sturdy peasant build–but more importantly, his stunning and steadfast opposition to chauvinism and Great Russian (or any other European) ethnic pride, condescension, and “leading role” in the multi-ethnic state he led.

Lenin shines here, throughout the edited volume, as the architect of the Affirmative Action/Positive Discrimination Empire, of the early USSR. This revolutionary state has such a bad reputation among the billionaires of today that one of them, a Russian oligarch (Vitaly Malkin) wrote, published and is sponsoring the free distribution of a work that links this emancipatory, multicultural social construction of the early 1920s to today’s BLM, and to Black Power–even the class enemy notices that Lenin’s legacy is at the core of the liberation of the Black woman and the Black man, as well as Asian, Russian, European and American woman and man (as oppressors and oppressed, of course, are both deformed by the same oppression).

This brings me to Joffre’s background, which is in theatre for peace, and the theatre of the oppressed, in post-conflict and conflict zones: Joffre is someone extremely and pointedly human. Only partly incidentally, my own region (post-‘state socialist’ East-Central Europe) is really the only place that is not represented in this magnificent collection of diverse authors–Hungary, once a country of a 1919 Soviet and of Georg Lukács, is not famous for its Leninists in the last decades. Joffre’s connections are as strong among theorists as within the world of theatre and he presents us with a Swiss female actress playing Lenin (Ursina Lardi) in an interview that enlightens and thrills.

The sheer diversity of the collection takes one’s breath away. Authors young and old, queer and old-style Marxist-Leninist, women and men submitted texts for this anthology, in English, German (translated by Joffre and also by Patrick Anderson), French (translated by Patrick Anderson), Russian (translated by G. Mamedov) and most importantly, Spanish and Portuguese (translated by the Spanish native speaker Joffre). The richness of Latin-American analysis and theory here, could be enough to fill a volume in itself. Indeed, for the average Anglophone speaker, who would be likely to learn about new Marxist ideas from Latin-America chiefly from Naomi Klein’s books (the author of this review includes himself in this category), this collection is a revelation on those riches: Bórquez, Cordero, Boron, del Roio’s interventions are stellar.

Another ‘decolonial’ group of Leninists whose works appear in this reader are ex-Soviet Central Asians: contemporary and late authors from Kyrgyzstan (Mamedov, Bokonbaev), Tajikistan (Suyarkulova). The visuals (edited by Johann Salazar) are photos of Lenin statues, bas-reliefs, mosaics, and frescos that stand (decaying) in the Republic of Kyrgyzstan, as well as images that aficionados of Soviet Bus Stops (also known as Facebook’s Brutalism Appreciation Society, British Brutalism Appreciation Society, etc.) will recognize.

The experiences of Central Asians and Russians are not silenced here–any academic from a global periphery or semi-periphery will understand how important this is. There is (to the utmost satisfaction of the author of this review) even an East German thinker, the son of GDR diplomats, Michael Brie, whose extremely subtle take on how Lenin should inform today’s Left, was not excluded by the authors. Indian voices, Vijay Prashad’s and also a contribution by a South Asian thinker from South Africa, Vashna Jagarnath’s, are also represented. In addition, Lenin’s oeuvre is problematized, criticized, and even (in comradely debate) attacked here (Kevin B. Anderson).

For a review in ROAPE, it is particularly exciting to note that African and Black voices are crucial for the editors. Joffre starts off the compilation with quotes by George Floyd and Langston Hughes (p. xii), commends the USSR for caring, celebrating and even paying royalties for young Congolese poets’ “public self-expression” (pp. 6-8). This is in the spirit of a critical solidarity with Lenin (p. xviii) and the attitude characterized by the quote “to grudgingly defend certain aspects of the 70+ year legacy of the USSR and other Communist experiments (p. ix).” African authors in the collection are: Vashna Jagarnath (pp. 51-60), Michael Neocosmos (pp. 201-212), and Maloadi Wa Sekake (pp. 213-224).

Jagarnath’s essay draws from Issa Shivji’s analysis of NGOization (“Within this context, NGOs are neither a third sector, nor independent of the state”) and stresses the specifically proletarian nature of both the 1905 Revolution in Russia (with its quintessentially proletarian weapon: the mass strike), and that of Lenin’s fight, with relevance today for South Africa and the continent. Three and a half thousand South Africans own as much as the bottom 32 million in the country (p. 53), making South Africa the most unequal country in the world–with 30% in the reserve army of labour. Marikana has 50 communal water taps for 60,000 families: a scandal.

Jagarnath refutes the importance of the technical shrinking of the proletariat in South Africa and elsewhere, by reminding us that Russia in 1917 had less than 20% of the populace classified as workers (and as we know even this is a liberal figure). Even though a minority, the employed, organized worker is an anchor for the compound, and will actively shape the consciousness of the people that she or he helps or lives with. In the West, where the sharing of food in kinship groups or the neighborhood is not seen any more, this is not expected–but in less individualistic, more communal, more humanistic formations, it is widespread still.

Michael Neocosmos of South Africa, a CODESRIA researcher, discusses the problem of the bureaucracy for Lenin after the Revolution. He points out how Lenin wanted to educate the unions, whereas Trotsky wanted to control them (p. 205). He also hails Chinese efforts, including Mao’s Cultural Revolution, in destroying bourgeois culture, and recommends following these examples in Africa (p. 209). Molaodi Wa Sekake, also of South Africa, quotes Ostrovsky on the liberation of humankind, opposes constructing a hagiography even for Lenin, posits that ANC and FRELIMO are today busy turning Lenin into a Trojan horse for neoliberalism in South Africa and Angola (p. 215), where the ANC also uses Lenin to pacify the masses (p. 214), whilst the academy is guilty of promoting pseudo-revolutionary speak (p. 218)–points we find difficult to disagree with! Lenin and the colonial question, Lenin as anti-imperialist (the constructor of the very theory of anti-imperialism) is also discussed (p. 220) in this chapter. There are, he warns, still, racist Leninists.

Whether Lenin was principally a political actor, a political actor-cum-theorist, or a theorist, depends on the authors’ vantage point and analysis. Lukács and his construction/deconstruction/analysis of Lenin’s thought figures strongly here, but other authors of this compendium deny that the idea of the vanguard party would have been central to Lenin’s thought (this is in the opinion of Renault, p. 193, who also calls Lenin “a calculator”), emphasizing his prudence instead of his take on the vanguard party (which he considers entirely tactical!) Others, especially thinkers from Africa, Asia and South America, see Lenin principally as the author of Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism–theory that arguably, may well be seen on par with Marx’s very own contribution to theory, worldwide.

An exception within this collection that presents a decolonial Lenin, is Slavoj Zizek in his chapter. Zizek did not consider this a minor assignment and he offers us here an extremely elegant, well thought-out, as well as scandalously un-decolonial, picture of Lenin. His historical points, even the most controversial that Stalin won against the Left Opposition by offering normalcy after ten years of war and mayhem: this is an argument that one finds difficult to contest. However, Zizek also claims here that “Communism is a European event, if there ever was one.” He brings neo-traditonalist Southern examples of rolling back Euro-centric epistemicide but claims this has nothing to do with Marxism (p. 292). He alleges that “capitalism functions much better when its excesses are regulated by some ancient tradition,” an assertion that is easy to make but more difficult to defend, and one that is easily contradicted by an even cursory analysis of today’s Nigerian political economy (very few would assert that Nigerian capitalism “functions well,” beyond producing profits for a small elite class). But more importantly even, Zizek forgets completely about the entire history of Marxist-Leninist states (from Mali through Guinea Conakry and Congo Republic, from Burkina Faso to Sudan, Ethiopia, Zimbabwe, Angola, Mozambique, and Madagascar, not to mention the role that Communism played in and around the ANC during the fight against apartheid) and also about African Marxist theory.

From Cabral through Fanon to Rodney, we may here make mention of African radicals, Marxists and (occasionally) Leninists, Eduardo Mondlane, Stephanie Urdang, Bernard Magubane, Ndeh Ntumazah, A. M. Babu, Thandika Mkandawire, Issa Shivji, Ernest Wamba Dia Wamba, Dani Wadada Nabudere, Ruth First, Ifeoma Okoye, Bade Onimode, Molara Ogundipe-Leslie, Amina Mama, Baruch Hirson, Govan Mbeki, Yusufu Bala Usman, Claude Ake, Biodun Jeyifo, Akin Adesokan, Biko Agozino, Ali Mazrui, Mahmood Mamdani, Baba Aye, and Usman Tar, as well as the recently deceased giant of decolonial Marxism and Leninism in Africa, Samir Amin. The African People’s Republics, and fighters such as Thomas Sankara, matter for Africa and for the World. Zizek once said that the worst part of Adorno and Horkheimer was that in all their works, one finds no reference to even the very existence of the GDR–and we can only salute Zizek for this incredibly pertinent point. What we see here though, is similar–Zizek is implicitly denying the validity of Africa’s Leninist moment, Marxist history, and the relevance of Communism for Africa (and Asia, the Middle East, and the Americas) by his historical European exceptionalism. This is no small matter. Communism is a global event, if ever there was one.

But Zizek does not define this anthology. The wealth of dialectical analysis here is staggering, and the tone set by Prashad and the South Africans (as well as Joffre’s unequivocal stance on the ongoing Kulturkampf, as it concerns Black people).

It is important to note that none of the contributors to this magnificent, multifaceted gem of a volume, see reason to embrace Lenin’s now increasingly problematic ‘line’ on the question of individual human rights (which of course he had labelled a ‘bourgeois distraction’), or his silence (or worse) on women’s issues as ‘political questions’. This also in turn proves that Leninism is alive and well, as a reflexive universe.

The volume celebrates the genuine political and theoretical achievements of Vladimir Ilyich, the revolutionary vozhd (leader) of the international proletariat, a class that he unwaveringly represented through his praxis, and even, through his political victory. Winning may be the hallmark of truth only for Nazis–but the pull of oblivion and losing, the political death wish, is also real. This volume is an antidote against such a seductive Thanatos in Africa and elsewhere.

Hjalmar Jorge Joffre-Eichhorn (editor), Patrick Anderson (language editor), Johann Salazar (photography): Lenin150 (Samizdat), Daraja Press, 2nd Edition, revised and expanded 2021.

Adam Mayer is the author of Naija Marxisms: Revolutionary Thought in Nigeria published by Pluto Press. Adam teaches International Relations at the Széchenyi István University Győr in Hungary and is a regular contributor to ROAPE.