In early 2014 an exhibition “The Vienna Model: Housing for the 21st Century City” was touring a number of U.S. cities, including New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Washington, D.C. Curated by Wolfgang Förster (Head of the Housing Research Department of the City of Vienna) and William Menking (Executive Editor of The Architect’s Newspaper and a professor at Pratt), “The Vienna Model” generated enormous interest among architects and housing specialists, especially in New York where its presentation at the Austrian Cultural Forum coincided with Mayor Bill de Blasio’s unveiling of his new housing agenda: to build 200,000 units of affordable housing over the next decade. Writing in New York Magazine Justin Davidson suggested that if the new mayor was “serious about making New York not just pleasant but just, he ought to go on a scouting trip to Vienna, where housing is considered a social good, not primarily a financial tool.”

The “Vienna Model” for providing subsidized housing is unquestionably one of the singular achievements of Austrian social policy and architectural production. But if we want to understand the full significance of that exemplary program, we need to return to the original site where the “Vienna Model” itself was shaped and the vital connection between social program and urban architectural form was first forged in the municipal building program of “Red Vienna” in the 1920s.

To begin, it is important to emphasize that the municipal project of Red Vienna was not a housing program, but an urban program. It was a comprehensive urban project that set itself task of making Vienna a more equitable environment for modern urban living. The building program–which involved the construction of 400 buildings known as Gemeindebauten, in which housing, social services and cultural institutions were distributed throughout the city–was the primary instrument of that project.1 By 1934, when Red Vienna itself came to a violent end with the Austrofascist rout of the socialist administration by Dollfuss and the Heimwehr, 200,000 people–one-tenth of the population of Vienna–had been rehoused, and the city provided with a vast new infrastructure of health and welfare services, clinics, childcare facilities, kindergartens, schools, sports facilities, public libraries, theatres, cinemas, and other institutions.

When the first socialist mayor of Vienna was elected in 1919, the Social Democrats determined to make Red Vienna a model of municipal socialism. “Capitalism,” Robert Danneberg, president of the new Provincial Assembly of Vienna declared, “cannot be abolished from the Town Hall. Yet it is within the power of great cities to perform useful installments of socialist work in the midst of capitalist society.”2 Red Vienna, in other words, was a project to change society by changing the city.

The new socialist Wohnkultur (dwelling culture) envisioned by the Social Democrats was conceived in terms of the traditional city and urban life. In part, this was because the city was the full extent of Red Vienna itself.3 But it was also because Austro-Marxist theory, which informed the program, held that the city offered positive cultural and social advantages to the proletariat.4 It was a stimulant to body and intellect, and it was the locus of the creative energy and the social progress that were shaping the modern world.

This was of course a deviation from the writings of Friedrich Engels and Karl Marx regarding the city. The Austro-Marxists were committed to finding a “third way” between Bolshevism and Reformism and to realizing a genuinely democratic Socialism through radical cultural and social change, rather than revolutionary violence. The process was to be one of hineinwachsen, slow growth from within, by creating institutions that would prepare the working class culturally and intellectually for its historical role.

The Gemeindebauten were conceived as the “social condensers” of Red Vienna, the vehicles for transforming the city. They contained housing, but also the Social Democrats’ extensive new infrastructure of social and cultural institutions that were embedded in them. They therefore created a new network of socio-cultural nodes throughout Vienna. It is important to note that the Social Democrats could not have focused on housing and social infrastructure if the previous Christian Social administration of mayor Karl Lueger (1844-1910) had not put in place the extensive network of technical infrastructure–electricity, gas, drinking water, sewage, tramlines, and a new metropolitan railway–in Vienna a generation earlier. The Social Democrats not only profited, but also learned a great deal from that earlier program.

So did their architects. Many of the architects who designed the largest and most important Gemeindebauten had studied with and trained in the office of Otto Wagner (1841-1918), the great Viennese architect of the fin-de-siecle and Professor at the Academy of Fine Arts. Some were working in the office when Wagner was designing the Wiener Stadtbahn (1894-1901) and developing his project for the Unbegrenzte Grossstadt (1911).

I have suggested elsewhere that the urban-active quality of the Gemeindebauten has a considerable affinity with the urban operations of Wagner’s municipal railway. This is worth revisiting. The Wiener Stadtbahn was both a major work of engineering that involved the construction of stations, viaducts, and bridges throughout the city, and an architectural work that physically tied the old city and new infrastructure together in all three dimensions. It did this in a remarkable way.

Architectonically, each of the stations, viaducts, bridges of the Stadtbahn reinforce the existing scale and patterns of its surroundings. At the same time, the system as a whole — tied together by tracks and rails that wind through the city–introduce a new metropolitan scale and order in the city. The Stadtbahn interweaves old and new fabric, local and translocal scales, the historical and contemporary city, in a way that allows both the old and new to co-exist and to (dialectically) shape the spaces of the modernizing city. Wagner made this integrating, mediating, and transforming function of the railway explicit by inscribing each of the new structures with street names so that they literally function as signs marking the points of intersection and overlap between the old and new.5

In the Gemeindebauten Wagner’s students translated the spatial dialectics of the Stadtbahn into an architecture of social relations between collective and individual in Red Vienna. That operation has considerable interest for today. If we look at how they did that, the urban architectural significance of the program as a whole and the instrumentality of the architecture itself become clear.

Typologically the Gemeindebauten were radically different from the modernist housing typology favored by the Congrès Internationale d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM) and built outside Frankfurt and Berlin during these years. These were ex-urban Siedlungen composed of parallel apt blocks, Zeilenbauten, which were oriented away from the street toward sun and grass. The Gemeindebauten, by contrast, were urban apartment blocks inserted into the existing urban fabric of Vienna itself. At first glance the Gemeindebauten appear to be traditional Central European perimeter blocks that have been monumentalized and provided with large garden courtyards so that they often occupy an entire urban block and sometimes several. Because of their seeming conventionality, the Gemeindebauten were sharply criticized at the time by architects of the modernist avant-garde and by architectural historians later, most notably, Manfredo Tafuri, who criticized them for their apparent lack of typological innovation.6

However, if we look closely at the plan of the Karl-Marx-Hof (1927-1930) by Karl Ehn (a student of Otto Wagner), it becomes immediately apparent that it deviates in important ways from the conventional urban building typology of Vienna. Not only is the Karl-Marx-Hof much larger than the traditional Viennese apartment building, but it also choreographs a carefully modulated entry sequence in its plan: from the public space of the street, into the semipublic space of the courtyard, to the communal space of the facilities (kindergartens, laundries, libraries, etc.), located in it, to the private spaces of the apartments.

What is the significance of this sequence? By bringing the public space of the city into the interior (and traditionally private space) of the block, the Gemeindebauten effectively turned the traditional urban block of the Central European city inside out. In so doing, they created hybrid spaces that were both part of the public domain of the city and part of the private and communal space of the new housing blocks.

The buildings themselves also challenge traditional concepts of boundary and type. Part dwelling space, part institutional space, part commercial space; they are multi-functional, multi-use structures that operate as both housing and urban infrastructural nodes, distributing the social services and cultural facilities provided by the Social Democratic municipality across the city. In short, they reproduced the city while reallocating its spaces and amenities.

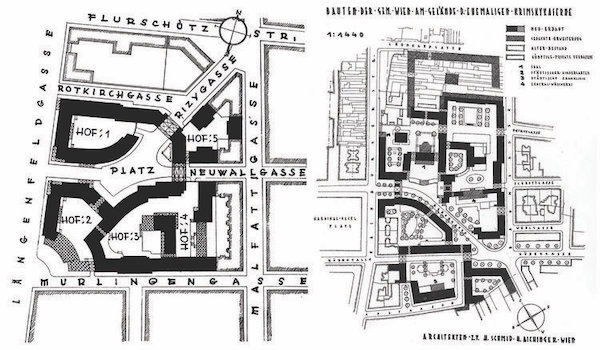

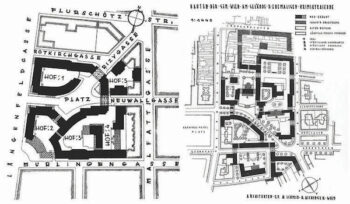

There are other ways in which the superblocks transformed the way in space was organized and used in the city. Take, for example, Schmid and Aichinger’s Rabenhof and Am Fuchsenfeld built in the mid-1920s. Each superblock contained several hundred apartments as well as libraries, laundry facilities, theatres, and 30-plus stores.

Carefully inserted into the fabric of Vienna the new buildings both preserve the existing urban structure of the city, and superimpose their own distinctive superblock scale and organization on it. The result is a complete interpenetration of public, private, and communal space. The effect is to blur the boundary not only between inside and outside, socialist housing block and bourgeois city, but also between insider and outsider. In doing so the Gemeindebauten signaled to their working class tenants that they were no longer “property-less strangers in a society that was not theirs.”7

Heinrich Schmidt and Hermann Aichinger, Rabenhof and am Fuchsfeld, Vienna, 1927. (Photo: Unknown/ Public Domain)

In short, the Gemeindebauten not only appropriated what would normally have been private space in the city (the interiors of the city blocks) for public use, but also created a new kind of commons, a new form of communal space in the city. And they did this without destroying the existing scale and fabric. Today, this kind of commonly owned space has more or less disappeared from the city.

So, what lessons can be derived from this close-looking at the urban operations of the Gemeindebauten of Red Vienna? First of all, the Gemeindebauten show that what something looks like, is not necessarily how it operates, especially in conditions of highly-charged political conflict such as those interwar Vienna. The Gemeindebauten looked like conventional Central European perimeter blocks writ large, but they actually undermined the logic of that type and, by reallocating the interiors of the blocks for communal use.

Second, Red Vienna was not the model for a housing program but rather for a more just urban society. The individual apartments in the Gemeindebauten were considered by their sponsors to be only a small part of the actual dwelling space provided by the city. They provided each family with its own hygienic, private living space. But that space did not fulfill Red Vienna’s own mandate to house its working population.

The individual unit was embedded in the larger socio-spatial matrix of the city, which in Red Vienna was considered to be the full measure of the proletarian home. In the brief period from 1923 to 1934 the broad institutional network and 400 new buildings erected throughout Vienna created social and spatial environments that conferred new political and economic status on Vienna’s working class.

They were testimony to the political control that the urban poor of Vienna had acquired over the shape and use of space in their city. Red Vienna gave the Viennese workers what they had voted for. It showed them that they had a voice; that they counted. It showed them how their own power, as fully enfranchised citizens of a democratic society, could be deployed. Ultimately, it granted them “the right to the city,” the right not merely to live in the city, but to participate in shaping it according to their own needs and desires.8

The third lesson is about the role of architecture. It was the urban active aspect of the architecture of Red Vienna that reclaimed private space in the city for public use, and that reconfigured the spaces of everyday life in ways that gave agency to their users, and granted them (to paraphrase David Harvey) the right to change themselves by changing the city.9

Today, when the large-scale provision of public services including housing, education, and healthcare is increasingly left to the market or to private companies operating on behalf of the state or other public bodies, we can learn a lot from re-reading Red Vienna and its legacy, not just for the remarkable housing program it spawned, but for the much more important knowledge embedded in its fabric about how cities can act on behalf of their citizens, how they can work to construct urban life around goals of social equity and public responsibility, and how–for those of us in the design disciplines–architectural intelligence can play a critical role in that effort.

This text is an abridgment of an article published in: Falkeis (Ed.), Urban Change. Social Design – Art as Urban Innovation ISBN 978-3-0356-1117-5 Series: Edition Angewandte

Eve Blau is a Professor of the History and Theory of Urban Form at Harvard University‘s Graduate School of Design. She is the author of The Architecture of “Red Vienna” 1919-1934 (1999) , German edition: Rotes Wien: Architektur 1919-1934. Stadt- Raum-Politik (2014). In 2015 she was awarded the Victor Adler-Staatspreis für Geschichte sozialer Bewegungen by the Austrian Ministry of Science, Research, and Economy.

Footnotes:

- ↩ The building program (land purchase and construction) was financed out of tax revenues, in particular by the new Housing Construction Tax (Wohnbausteuer), which was sharply graded to put the burden on the rich and was written off as non-recoverable cost to the municipality, ie the capital cost did not have to be covered by the rents. Rents were minimal (3.5% of a semi-skilled worker’s income) to keep wages low and make Austrian products competitive, and were intended only to cover maintenance and repair costs. The buildings were designed by more than 190 architects, and built in a period of a little over ten years. See further, Eve Blau, The Architecture of Red Vienna: 1919-1934 (Camrbidge: MIT Press, 1999), and Rotes Wien: Architektur1919-1934. Stadt-Raum-Politik (Vienna:Birkhäuser, 2014)

- ↩ Robert Danneberg, Vienna under Socialist Rule, trans. H. J. Stenning (London: Labour Party, 1928), 52. See Gulick, Austria, 2:1367.

- ↩ Vienna as a Bundesland of the Federal Republic of Austria, could not expand beyond the existing municipal boundary (set in 1905) without constitutional amendment.

- ↩ Austro-Marxism was formulated before World War I by a group of Marxist thinkers and leaders of the Austrian socialist movement, including Max Adler, Otto Bauer, and Karl Renner. See further, Rabinbach, Crisis of Austrian Socialism: From Red Vienna to Civil War 1927-1934. (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1983), 30. See also Felix Czeike, Wirtschafts- und Sozialpolitik der Gemeinde Wien in der Ersten Republik (1919-1934), Wiener Schriften, Heft 6, 11 (Vienna: Jugend und Volk, 1958,1959).

- ↩ See Eve Blau, “Supranational Principle as Urban Model: Otto Wagner’s Großstadt and City-Making in Central Europe’ in Histoire de l’art du xixe siècle (1848-1914), bilans et perspectives (Paris: Collections des Rencontre de l’Ecole du Louvre, 2012), 501-514.

- ↩ Manfredo Tafuri, ‘Das Rote Wien’; Politica e forma della residenza nella Vienna socialista, 1919-1933,” in Tafuri, Vienna Rossa (Milan: Electa, 1980), pp. 94, 119-139.

- ↩ Charles A. Gulick, Austria from Hapsburg to Hitler, 2 vols. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1948): 1:504.

- ↩ Henri Lefebvre, Le Droit à la ville (Paris: Anthropos, 1968)

- ↩ David Harvey, “The Right to the City,” New Left Review 53 (Sept Oct 2008), p. 23.