One revolutionary consequence of the expansion of digital technologies is their ability to change the fabric of capitalism: As they harvest enormous amounts of data, “Big Tech” firms are becoming more like banks. For instance, if the traces left by our individual pathways as we navigate the internet reveal more about our ability to repay than our credit score, then chances are that Big Tech firms will be tomorrow’s lenders. The information revolution occurring these days is a revolution of the financial system.

In this new INET Working Paper, we ponder those transformations by adding the perspective of history. As we show, the questions that agitate us today are by no means novel. In fact, data harvesting played a crucial role in bringing about the First Era of financial globalization in the 19th century. “Big Data,” Victorian style, was a fundamental pillar of the export of capital and it shaped the contours of international lending–who received money, how, and at which price.

We demonstrate this by studying a strange financial institution, which has been often described but never quite understood. An enormous fraction of sovereign debt loans issued in the leading capital markets of the time included perplexing “hypothecations.” Borrowers “pledged” to creditors about anything: Railways, canals, forests, telegraphs, custom revenues, the profit of tobacco monopolies, and even guano, a stinking bird manure which Peru collected in Pacific islands. In London, about half of the sovereign loans issued at the time had such promises. The mystery is that these pledges were not at all enforceable and in practice, when countries defaulted, the assets invariably remained with the defaulter.

Against this backdrop, some authors have suggested that the hypothecations were a scam, intended to lure investors by giving them a false sense of security. But this is inconsistent with the fact that the contracts never claimed that the repossession would ever take place. The prospectuses were quite transparent on the point. Other researchers have hypothesized that perhaps, some of the hypothecations were enforceable. Perhaps export commodities, such as guano, could be seized when they reached foreign ports. In fact, courts of justice ruled that sovereign assets enjoyed immunity, even when aboard a ship in the London docks, within walking distance of the Court of Chancery.

We argue that the clauses were valuable because they were information. While silent on the process whereby the assets would be repossessed, prospectuses were exceedingly detailed when it came to identifying the resource and describing the algorithm whereby information on foreign payments from the sources would be released. Sworn information intermediaries were involved, monitoring the execution of payments from, say, the borrower’s custom house. The funds became traceable in real-time: If for instance the money for the semester’s dividend was not forthcoming by a certain date specified in the contract, the intermediaries would write or telegraph to the agents for the loan London, and the credit event would be documented in the newspapers.

This was tremendously valuable because at the time, except for a few countries, fiscal information was fragmentary at best. If it existed at all, it often arrived with a long lag. In fact, state budgets were not always published and final accounts were even less frequently constructed. The position of the external debt was not known, which is not really surprising in view of the IMF’s own discovery, in the aftermath of the Asian Crisis in 1997, that its debt numbers were seriously wanting. Such abysmal information asymmetries ought to have killed capital exports. But this did not occur because of the hypothecations and, as a result, we find strong evidence of lower interest rates for countries and loans that were hypothecated. We suspect that the effect was even larger on quantities because the technology really threw open new markets that would have probably remained closed otherwise, given their opacity.

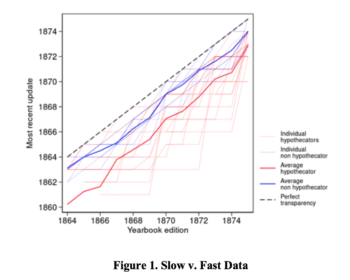

The Figure summarizes the availability of revenue figures according to the Statesman’s Yearbook, a leading contemporary source for fiscal data. On the x-axis, we list the year of publishing of each issue of the Yearbook. On the y-axis, we list the year of the most recent update for each sovereign revenue figure. Real time disclosure (perfect transparency) is represented by the 45° line.

Hypothecations forced the inventory of national resources. They encouraged identification of sources of income and the design of policies to valorize them. The numbers delivered in prospectuses were not economic “fundamentals” in the modern sense, though they served a similar function. As we find, the mean ratio between the debt service and the income from the source hovered around 1/2. The use of clauses eased monitoring in yet another way, because each pledge could be cross-checked against past pledges for consistency. Given identified resources, more borrowing would force indebtedness to go up unless other sources of income were identified. But at one point, the inventory would be complete and the sovereign would run short of information to disclose. If investors saw repetition (the repledging of the same asset), they understood that something was going wrong and that the debt was becoming unsustainable.

In the paper, we provide evidence in support of this interpretation of 19th-century capital export as driven by Victorian-style Big Data. Surveying contemporary sources, we show that the incidence of hypothecations increased markedly in countries that had more lacunary fiscal data: For instance, the slower fiscal data was to come, the more likely the country was to rely on hypothecations (See Figure 1). We also show that some opaque countries, such as Brazil could do away with hypothecations because they enjoyed a privileged link with a prestigious underwriter. In the case of Brazil, the identity of the underwriter, who was prestigious and knowledgeable of the country, substituted for disclosure. Finally, we provide evidence of the involvement of lawyers in the drafting of contracts, not in order to trick investors with clever clauses, but because false data was criminalized.

Our contention that data gathering and its harnessing by enterprising financiers shaped the deep transformation of capitalism at that point has important theoretical and policy implications. First, we observe a novel, direct role of collateral pledges as information collection technology, particularly relevant in weak enforcement environments. This squares with (and reinforces evidence of) the disruptive power of Big Tech finance. Indeed, Big Tech firms employ alternative, likely cheaper information technologies and can lend at an advantage, relying less on collateral. Second, our investigation underscores the importance of disclosure algorithms and mechanism designs as key features of information institution-building. We believe that a similar logic is at work today, for instance in the role played by the extensive (and intriguing) use of collateral pledges in Chinese lending to developing countries.

Our contention that data gathering and its harnessing by enterprising financiers shaped the deep transformation of capitalism at that point has important theoretical and policy implications. First, we observe a novel, direct role of collateral pledges as information collection technology, particularly relevant in weak enforcement environments. This squares with (and reinforces evidence of) the disruptive power of Big Tech finance. Indeed, Big Tech firms employ alternative, likely cheaper information technologies and can lend at an advantage, relying less on collateral. Second, our investigation underscores the importance of disclosure algorithms and mechanism designs as key features of information institution-building. We believe that a similar logic is at work today, for instance in the role played by the extensive (and intriguing) use of collateral pledges in Chinese lending to developing countries.

Overall, while multiple authors including Douglass North have theorized the importance of property rights, of the rule of law, and of parliamentary control of the budget when discussing comparative international development, we show that other avenues of development, relying on digital contents, were organized with the help of lawyers, and ended up playing a critical role. That this information accumulated in the markets of capital-exporting countries also sheds light on the relationship that existed between the political economies of data accumulation and political power. These lessons from another Age ought to be carefully considered as new forms of data harvesting are once again on the verge of transforming the world.