Dear friends,

Greetings from the desk of the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

As the last private plane takes off from the Glasgow airport and the dust settles, the detritus of the 26th United Nations Climate Change Conference, COP26, remains. The final communiqués are slowly being digested, their limited scope inevitable. António Guterres, Secretary-General of the United Nations, closed the proceedings by painting two dire images: ‘Our fragile planet is hanging by a thread. We are still knocking on the door of climate catastrophe. It is time to go into emergency mode–or our chance of reaching net zero will itself be zero’. The loudest cheer in the main hall did not erupt when this final verdict was announced, but when it was proclaimed that the next COP would be held in Cairo, Egypt in 2022. It seems enough to know that another COP will take place.

An army of corporate executives and lobbyists crowded the official COP26 platforms; in the evening, their cocktail parties entertained government officials. While the cameras focused on official speeches, the real business was being done in these evening parties and in private rooms. The very people who are most responsible for the climate catastrophe shaped many of the proposals that were brought to the table at COP26. Meanwhile, climate activists had to resort to making as loud a noise as possible far from the Scottish Exchange Campus (SEC Centre), where the summit was hosted. It is telling that the SEC Centre was built on the same land as the Queen’s Dock, once a lucrative passageway for goods extracted from the colonies to flow into Britain. Now, old colonial habits revive themselves as developed countries–in cahoots with a few developing states that are captured by their corporate overlords–refuse to accept firm carbon limits and contribute the billions of dollars necessary for the climate fund.

The organisers of COP26 designated themes for many of the days during the conference, such as energy, finance, and transport. There was no day set aside for a discussion of agriculture; instead, it was bundled into ‘Nature Day’ on 6 November, during which the main topic was deforestation. No focused discussion took place about the carbon dioxide, methane, or nitrous oxide emitted from agricultural processes and the global food system, despite the fact that the global food system produces between 21% and 37% of annual greenhouse gas emissions. Not long before COP26, three United Nations agencies released a key report, which offered the following assessment: ‘At a time when many countries’ public finances are constrained, particularly in the developing world, global agricultural support to producers currently accounts for almost USD 540 billion a year. Over two-thirds of this support is considered price-distorting and largely harmful to the environment’. Yet at COP26, there was a notable silence around the distorted food system that pollutes the Earth and our bodies; there was no serious conversation about any transformation of the food system to produce healthy food and sustain life on the planet.

Instead, the United States and the United Arab Emirates, backed by most of the developed states, proposed an Agriculture Innovation Mission for Climate (AIM4C) programme to champion agribusiness and the role of big technology corporations in agriculture. Big Tech companies, such as Amazon and Microsoft, and agricultural technology (Ag Tech) firms–such as Bayer, Cargill, and John Deere–are pushing a new digital agricultural model through which they seek to deepen their control over global food systems in the name of mitigating the effects of climate change. Stunningly, this new, ‘game-changing’ solution for climate change does not mention farmers anywhere in its key documents; after all, it seems to envisage a future that does not require them. The entry of Ag Tech and Big Tech into the agricultural industry has meant a takeover of the entire process, from the management of inputs to the marketing of produce. This consolidates power along the food chain in the hands of some of the world’s largest food commodity trading firms. These firms, often called the ABCDs–Archer Daniels Midland, Bunge, Cargill, and Louis Dreyfus–already control more than 70% of the agricultural market.

Ag Tech and Big Tech firms are championing a kind of uberisation of farmlands in an effort to dominate all aspects of food production. This ensures that it is the powerless smallholders and agricultural workers who take on all the risks. The German pharmaceutical company Bayer’s partnership with the U.S. non-profit Precision Agriculture for Development (PAD) intends to use e-extension training to control what and how farmers grow their produce, as agribusinesses reap the benefits without taking on risk. This is another instance of neoliberalism at work, displacing the risk onto workers whose labour produces vast profits for the Ag Tech and Big Tech firms. These big firms are not interested in owning land or other resources; they merely want to control the production process so that they can continue to make fabulous profits.

The ongoing protests by Indian farmers, which began just over a year ago in October 2020, are rooted in farmers’ justified fear of the digitalisation of agriculture by the large global agribusinesses. Farmers fear that removing government regulation of the marketplaces will instead draw them into marketplaces controlled by digital platforms that are created by companies like Meta (Facebook), Google, and Reliance. Not only will these companies use their control over the platforms to define production and distribution, but their mastery over data will allow them to dominate the entire food cycle from production forms to consumption habits.

Earlier this year, the Landless Workers Movement (MST) in Brazil held a seminar on digital technology and class struggle to better understand the tentacles of the Ag Tech and Big Tech firms and how to overcome their powerful presence in the world of agriculture. Out of this seminar emerged our most recent dossier no. 46, Big Tech and the Current Challenges Facing the Class Struggle, which seeks to ‘understand technological transformations and their social consequences with an eye towards class struggle’ rather than to ‘provide an exhaustive discussion or conclusion on these themes’. The dossier summarises a rich discussion about several topics, including the relationship between technology and capitalism, the role of the state and technology, the intimate partnership between finance and tech firms, and the role of Ag Tech and Big Tech in our fields and factories.

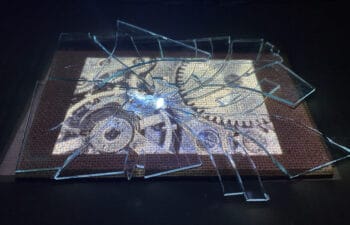

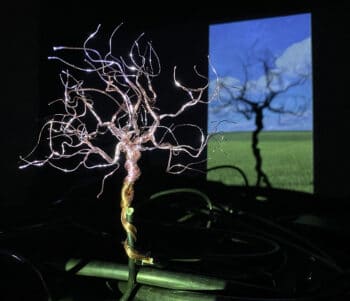

Dossier 46 cover – The images in this dossier aim to visualise the materiality of the digital world we live in. (Designed by the Art Department of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research based on photographs by Ingrid Neves)

The section on agriculture (‘Big Tech against Nature’) introduces us to the world of agribusiness and farming, where the large Ag Tech and Big Tech firms seek to absorb and control the knowledge of the countryside, shape agriculture to suit the interests of the big firms’ profit margins, and reduce agriculturalists to the status of precarious gig workers. The dossier closes with a consideration of five major conditions that are behind the expansion of the digital economy, each of them suited to the growth of Ag Tech in rural areas:

- A free market (for data). User data is freely siphoned off by these firms, which then convert it into proprietary information to deepen corporate control over agricultural systems.

- Economic financialisation. Data capitalist companies depend on the flux of speculative capital to grow and consolidate. These companies bear witness to capital flight, shifting capital away from productive sectors and towards those that are merely speculative. This puts increasing pressure on productive sectors to increase exploitation and precarisation.

- The transformation of rights into commodities. The fact that public intervention is being superseded by private companies’ meddling in arenas of economic and social life subordinates our rights as citizens to our potential as commodities.

- The reduction of public spaces. Society begins to be seen less as a collective whole and more as the segmented desires of individuals, with gig work seen as liberation rather than as a form of subordination to the power of large corporations.

- The concentration of resources, productive chains, and infrastructure. Centralisation of resources and power amongst a handful of corporations gives them enormous leverage over the state and society. The great power concentrated in these corporations overrides any democratic and popular debate on political, economic, environmental, and ethical questions.

In 2017, at COP23, participating countries set up the Koronivia Joint Work on Agriculture (KJWA), a process that pledged to focus on agriculture’s contribution to climate change. KJWA held a few events at COP26, but these were not given much attention. On Nature Day, forty-five countries endorsed the Global Action Agenda for Innovation in Agriculture, whose main slogan, ‘innovation in agriculture’, aligns with the goals of the Ag Tech and Big Tech sector. This message is being channelled through CGIAR, an inter-governmental body designed to promote ‘new innovations’. Farmers are being delivered into the hands of Ag Tech and Big Tech firms, who–rather than committing to avert the climate catastrophe–prioritise accumulating the greatest profit for themselves while greenwashing their activities. This hunger for profit is neither going to end world hunger, nor will it end the climate catastrophe.

The images in this newsletter come from dossier no. 46, Big Tech and the Current Challenges Facing the Class Struggle. They build on a playful understanding of the concepts underpinning the digital world: clouds, mining, codes, and so on. How to depict these abstractions? ‘A data cloud’, writes Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research’s art department, ‘sounds like an ethereal, magical place. It is, in reality, anything but that. The images in this dossier aim to visualise the materiality of the digital world we live in. A cloud is projected onto a chipboard’. These images remind us that technology is not neutral; technology is a part of the class struggle.

The farmers in India would agree.

Warmly,

Vijay