This April, the Iowa Department of Corrections issued a ban on charities, family members, and other outside parties donating books to prisoners. Under the state’s new guidelines, incarcerated people can get books only from a handful of “approved vendors.” Used books are prohibited altogether, and any new reading material is subject to a laundry list of restrictions.

The policy is harsh, but far from unique. In fact, it’s only the latest in a wave of similar bans. In 2018, the Michigan prison system introduced an almost identical set of rules, and Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Washington have all made attempts to block book donations, which were only rolled back after public outcry. Across the United States, the agencies responsible for mass imprisonment are trying to severely limit incarcerated people’s access to the written word—an alarming trend, and one that bears closer examination.

The official narrative is that donated books could contain “contraband which poses a threat to the security, good order, or discipline of the facility”—the language used in Michigan—and should be banned for everyone’s safety. This is a flimsy justification that begins to fall apart under even the lightest scrutiny. While it’s true that contraband is often smuggled into prisons (cell phones, tobacco, and marijuana being some of the most popular items), it’s not originating from nonprofit groups like the Appalachian Prison Book Project or Philadelphia’s Books Through Bars. In fact, twelve of the seventeen incidents used to justify a book ban in Washington didn’t involve books at all.

Instead, the bulk of the contraband in today’s prisons is smuggled in by guards themselves, who profit handsomely from their illicit sidelines, sometimes making as much as $300 for a single pack of cigarettes. If prison officials’ concerns were genuine, the appropriate move would be to limit the power and impunity of their officers—not snatch books away from those who are already powerless. The old cartoon scenario of a hollow book with a saw or a gun inside just isn’t realistic, and its invocation is a sign that something else is going on.

That “something else,” predictably enough, is profit. With free books banned, prisoners are forced to rely on the small list of “approved vendors” chosen for them by the prison administration. These retailers directly benefit when states introduce restrictions. In Iowa, the approved sources include Barnes & Noble and Books-a-Million, some of America’s largest retail chains—and, notably, ones which charge the full MSRP value for each book, quickly draining prisoners’ accounts. An incarcerated person with, say, $20 to spend can now only get one book, as opposed to three or four used ones; in states where prisoners make as little as 25 cents an hour for their labor, many can’t afford even that.

With e-books, the situation is even worse, as companies like Global Tel Link supply supposedly “free” tablets which actually charge their users by the minute to read. Even public-domain classics, available on Project Gutenberg, are only available at a price under these systems—and prisons, in turn, receive a 5% commission on every charge. All of this amounts to rampant price-gouging and profiteering on an industrial scale.

The rise of these private vendors has also been mirrored by the systematic dismantling of the prison library system. In the last ten years, budgets for literacy and educational resources have seen dramatic cuts, reducing funding to almost nothing, and incarcerated people have been deprived as a result. In Illinois, for instance, the Department of Corrections spent just $276 on books across the entire state in 2017, down from an already meager $605 the previous year. (This means, incidentally, that each of the state’s roughly 39,000 prisoners was allotted seven-tenths of a cent.) Oklahoma, meanwhile, has no dedicated budget for books at all, requiring prison librarians to purchase them out-of-pocket. Many books in its small stock are “falling apart, dilapidated and may be missing some pages.” These cuts are part of capitalism’s more general push to privatize or eliminate public goods and services—libraries among them—so massive corporations can receive windfalls. In prisons, the method is especially devastating.

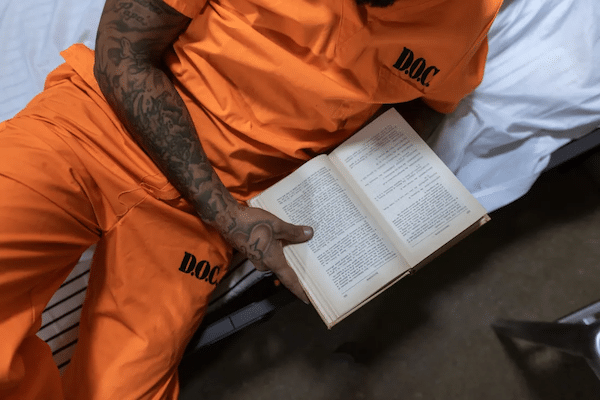

These practices become all the more abhorrent when you consider the impact books can have behind bars. By now, the social science on their benefits is well-established: in one study, the University of Massachusetts found that incarcerated people who took part in reading programs were much better equipped to deal with the outside world on their release, showing only an 18.75% rate of recidivism compared to a control group’s 45%. Other studies have revealed a wide range of mental health benefits, with books providing improved self-esteem, communication skills, and a sense of purpose in life. For some, the results are even more pronounced. Malcolm X famously got his political education from a prison library, working his way through Gandhi, Nietzsche, and W.E.B. Du Bois in his time at Norfolk Prison, and wrote powerfully about the experience in his autobiography:

I have often reflected upon the new vistas that reading opened to me. I knew right there in prison that reading had changed forever the course of my life. As I see it today, the ability to read awoke inside me some long dormant craving to be mentally alive. I certainly wasn’t seeking any degree, the way a college confers a status symbol upon its students… Not long ago, an English writer telephoned me from London, asking questions. One was, ‘What’s your alma mater?’ I told him, ‘Books.’

Now, imagine if the State of Massachusetts had defunded its libraries and banned anyone from sending books behind prison walls—that remarkable evolution might never have occurred, and the world would have lost one of its most important radical voices. Today, other inmates have reportedthat reading meant “the difference between just giving up mentally and emotionally and making it through another day, week, or year,” countering the dehumanizing effects of their imprisonment. A book can offer a brief, irreplaceable moment of calm in hellish circumstances. It may be the only thing keeping someone from suicide or self-harm. This is what profiteering companies like Global Tel Link are trying to take away, all for the sake of lining their own pockets. Not content with locking up the body, they want to slam shut the doors of the mind as well.

Even in states with no outright ban on book donations, there are still “content-specific” bans on particular titles and subjects. These exist in virtually every American prison, and have become more pervasive with each passing year. Like so many things in the carceral system, the pattern of restrictions is flagrantly racist. For instance, many prisons have blanket bans on “urban” novels, a genre revolving around crime and intrigue in African-American communities. These are treated as contraband, and can’t be obtained through approved sources. Meanwhile, equally violent novels about white criminals, such as The Godfather or the Hannibal Lecter series, are allowed with no restrictions. Works by African-American activists also come under fire, on the grounds that they might be “dangerously inflammatory,” with disturbing frequency. In Florida, the Department of Corrections bans Police Brutality by Elijah Muhammad, Political Prisoners, Prisons, and Black Liberation by Angela Davis, and many similar texts; it has no such bans for Mein Kampf or The Turner Diaries. (Protean, interestingly, is not banned anywhere—yet.)

Restricting the right to read, in this way, is a tactic intimately bound up with the history of American racism and white supremacy. In his Narrative of the Life, Frederick Douglass recalls the way his one-time captor, the slaveholder Mr. Auld, raged against the possibility of his becoming literate, warning of the “harm” (to him) that would result. In many Southern states, it was actually illegal to teach a slave so much as the alphabet, lest they use the knowledge to free themselves. With time, the carceral state took the place of the slaveholding one, but the impulse to control the written word remained the same. In his landmark prison memoir Soul on Ice, Eldridge Cleaver, the former Minister of Information for the Black Panther Party, details the racism he experienced from the censor:

They also have this sick thing going when it comes to books by and about Negroes. Robert F. Williams’s book, Negroes with Guns, is not allowed anymore. I ordered it from the state library before it was too popular around here. I devoured it and let a few friends read it before the librarian dug it and put it on the blacklist. Once I ordered two books from the inmate canteen with my own money. When they arrived here from the company, the librarian impounded them, placing them on my ‘property’ the same as they did my notebooks.

Although it took place in the mid-1950s, this scene is easily recognizable to anyone in prison today. Officials identify a “radical” book or periodical, perceive it as a threat to the status quo, and move swiftly to get rid of it, trampling prisoners’ human rights in the process. Even the language used is sickly ironic—then, as now, the “black list” is quite literally a list of Black thinkers and their works.

Tellingly, the usual circle of “free speech” pundits—the Shapiros and Crowders of the world, who swell with indignation whenever a bigoted uncle gets banned from Facebook—have little to say about censorship in prisons. (This may, in some ways, be a mercy; at least they’re not actively making the situation worse.) What’s more surprising, though, is that groups with a history of sympathy toward civil liberties are also quiet. In the American Library Association’s popular “Banned Books Week,” plenty of attention is given to the removal of books from school and municipal libraries—an important issue, to be sure—but significantly less to the same practices in prisons, where censorship is far more widespread, and those affected have little ability to seek other options. This omission is part of a shameful pattern in American society, where many people simply don’t think about the incarcerated on a day-to-day basis, let alone sympathize with their worsening conditions. For wardens and administrators, it’s all too easy to keep the whole matter out of sight, and out of mind.

One of the most common arguments for the American carceral system, and its continued existence, is that of rehabilitation. According to its defenders, a prison is not simply a place of suffering, where unwanted populations are sent to disappear. Nor is it a callous money-making machine, intended to squeeze free labor from them in a regime of functional slavery. Instead, prison rehabilitates—so the story goes. The very word “penitentiary” invokes ideas of penitence, re-evaluation, and personal growth, the ostensible goals of such an institution. In these terms, the basic legitimacy of mass imprisonment, and its allegedly positive social role, is taken for granted—to the point that it forms a central theme in our Vice President’s entire career. But the practice of book banning exposes the lie. Not only do American prisons have little interest in education, healing, and growth, but they will actively prevent them the moment there is a dollar to be made or an ounce of power to be secured. This is what actually happens on the ground, and it demolishes America’s claim to moral authority.

In another light, though, there may be hope to be found here. Historically, systems of censorship and control are at their strictest when the regime in power knows it has something to hide, and fears exposure—if its position were unassailable, there would be no need. (Consider, for example, Saudi Arabia’s stranglehold on Internet access, or the Putin government’s penchant for censoring political exposés.) In recent years, America has been grappling with issues of race, class, and state authority like never before—both in the national discourse, and in the streets, where police have been driven back and their precincts burned to the ground. Prisons in cities like St. Louis have seen mass uprisings—not “riots” of random violence, as the press would have it, but concerted political actions with specific demands, including fair wages and protection from COVID-19.

In this climate it’s no longer inconceivable, as it was for so many years, that the prison-industrial complex as we know it could simply cease to be. As a result, the people who benefit most from its existence—the comfortable bourgeois, and their political organs—have responded by cracking down on dissent. This trend can be seen both in prisons, where writers like Davis and Muhammad are suddenly too “inflammatory” to allow, and outside them, where conservative politicians have made the academic study of racism their newest bogeyman. Legitimate power does not fear discussion and study. Rather, the prohibition of those things is a tacit acknowledgment of its illegitimacy, and of just how nervous the leaders of the whole rickety structure are getting.

This also means that, as a rule of thumb, anything the carceral state wants to prevent is more than likely a good to be pursued. In the wake of recent elections, many concerns of the left have been cast adrift, and, in the Biden era, we can lack for obvious means of pursuing change. Sending free books to people in prison is one such means, and if the recent backlash against donations is anything to judge by, it’s a potent one. For those who live in a major city, there may well be an organization doing this already. (The ALA keeps a good list, and a quick Internet search will reveal more.) If not, one can always be formed. In either case, providing books and other reading material is an important and under-practiced form of mutual aid for those who have been locked away—and equally, a way of landing a blow against profiteers and exploiters, who so richly deserve one. Until the day when the last prison falls, these small acts of resistance and solidarity will remain vital.

Alex Skopic is a freelance writer from Springville, Pennsylvania. His work has appeared in Anthracite Unite, Current Affairs, and Vastarien: A Literary Journal, among other places.