Fox News White House correspondent Peter Doocy asked a bizarre question at President Joe Biden’s November 3 press briefing. The president seemed to misunderstand the question, which referred to potential settlements of a lawsuit stemming from the Trump administration’s notorious 2017–18 family separation policy. Biden bungled his response, apparently calling reports about the settlement “garbage.”

The New York Post (11/4/21) was either lying, was never told or had forgotten about the dubiousness of Peter Doocy’s question.

Not surprisingly, the media ran with the story of Biden’s blunder. Doocy’s question, on the other hand, was mostly ignored or played down.

The Fox reporter had asked whether the possible settlements, reportedly as high as $450,000 a person, “might incentivize more people to come over illegally.” But as the Washington Post’s Aaron Blake (11/4/21) noted, the question didn’t make sense:

The [family separation] policy is no longer in effect (thus rendering such future payments inapplicable for would-be border-crossers).

Other reporters, however, didn’t seem to notice this issue. CNN’s Daniel Dale (11/5/21) factchecked Biden’s answer, but not the notion that a settlement based on a terminated policy could somehow incentivize future migration. Over at Politico (11/3/21), Myah Ward reported Doocy’s question, but not how strange it was. New York Times White House correspondent Zolan Kanno-Youngs (11/3/21) didn’t even bother to report the question, merely noting that Biden was “asked on Wednesday about compensating the migrants.”

In contrast, the New York Post (11/4/21) (owned, like Fox, by the Murdoch family) responded with an editorial backing Doocy’s implication that the settlement could encourage unauthorized migration. This followed an earlier Post article (10/29/21) that quoted a total of 11 Republican politicians denouncing the reported settlement amount. Neither piece mentioned the public outrage at the practice of tearing apart children and parents fleeing violence (PBS, 6/18/18)—an outrage so intense that the Trump administration was forced to end the policy in June 2018 (NPR, 6/20/18).

Misperception or misrepresentation?

Unfortunately, this imbalance is typical of much corporate media immigration coverage. Right-wing media figures and Republican politicians get little pushback when they promote evidence-free, often absurd claims about incentives for unauthorized immigration.

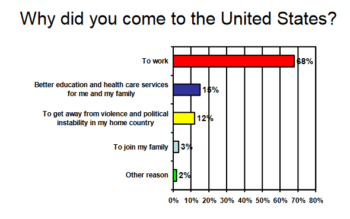

Chart: Manhattan Institute/National Immigration Forum (3/30/06)

Doocy didn’t answer emails asking him to explain his November 3 question, but presumably he was referring to a misperception migrants might have that the Biden administration was handing out money to border crossers—a misperception the right has worked overtime to create. But two surveys of unauthorized immigrants indicate that misperceptions about U.S. migration policies don’t actually play a significant role in spurring unauthorized border crossing.

In 2005, the Bendixen & Associates polling company interviewed 233 undocumented immigrants for a study sponsored by the National Immigration Forum and the conservative Manhattan Institute. The study reported that 68% of the subjects said they’d migrated here to work, 15% to get better education and healthcare for themselves and their families, 12% to escape violence and 3% to join their families. Just 2% cited other reasons.

Eight years later, Latino Decisions surveyed 400 undocumented immigrants for the National Association of Latino Elected and Appointed Officials (NALEO) Educational Fund and America’s Voice Education Fund. This study reported that 39% of the people interviewed came for better jobs and economic opportunities, 38% for a better life for family or children, 12% to join family members, and 4% to escape political oppression. Other reasons accounted for 6%.

What history shows

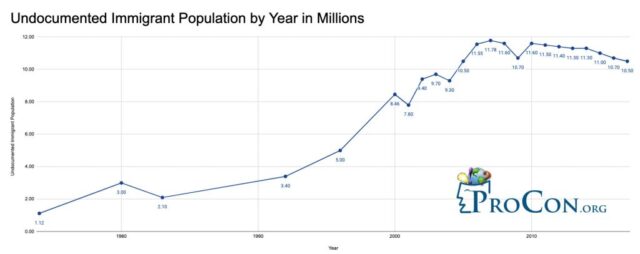

The population of unauthorized immigrants has been mostly declining since 2007. (Chart: ProCon.org)

Migration patterns over the last half-century support the findings of the two surveys. Increases and declines in unauthorized immigration mostly correlate with changes in job opportunities and other economic conditions in the United States and in nearby countries.

Vox (7/4/21) pointed out that a “law to legalize the undocumented population… could actually reduce unauthorized immigration and give the U.S. economy a boost.”

The U.S. undocumented population grew at a fairly steady rate during the first half of the period, but the pattern had started changing by the mid-1990s, when the undocumented population increased sharply, tripling by 2007. It then gradually declined through 2019. There was an increase in asylum seekers after 2010, although not enough to reverse the overall decline.

The U.S. economy was growing during most of the 1990s, but Mexicans continued to suffer from the effects of the 1982 debt crisis. Their situation worsened after a 1994–95 financial crisis, and NAFTA’s disruption of the rural economy left millions of Mexicans unemployed or underemployed. The resulting increase in undocumented immigration from Mexico eased a little in the early 2000s, as the Mexican economy stabilized; border crossings dropped further when the 2007–09 Great Recession knocked out millions of U.S. jobs.

The more recent increase in asylum seekers came as levels of violence rose in El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras.

It’s true that one U.S. policy helped swell the undocumented population, but not because the policy attracted migrants. The Clinton White House started a significant intensification of border enforcement; this continued through subsequent administrations. The policy made border crossings more dangerous, resulting in at least 7,000 border deaths from 1998 to 2020 (Guardian, 1/30/21).

And as Vox reporter Nicole Narea (7/4/21) explained, Princeton sociologist Douglas Massey and other scholars have found that the stepped-up enforcement ended a circular pattern in which Mexicans had alternated periods working in the United States with periods spent at home. As crossing the border became riskier and more expensive, many Mexican workers chose to settle here instead of returning to Mexico.

Long wait for ‘amnesty’

This history explains most spikes in unauthorized immigration, but anti-immigrant forces prefer to make up their own explanations.

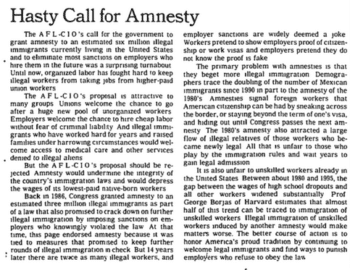

The New York Times (2/22/00) blamed the rise in unauthorized immigration on a 1986 amnesty—not on the trade policies that it editorially supported.

Their favorite centers on a 1986 law that provided a path for legalization to some 2.7 million immigrants during the Reagan administration. The right claims that the sharp increase of the undocumented population during the mid-1990s—seven or eight years after the law went into effect—somehow resulted from this “Reagan amnesty.” So legalizations must “beget more illegal immigration,” as the New York Times (2/22/00) announced in a 2000 editorial:

Amnesties signal foreign workers that American citizenship can be had by sneaking across the border, or staying beyond the term of one’s visa, and hiding out until Congress passes the next amnesty.

The Times and other centrist media now seem to have backed away from this post hoc, propter hoc argument, but they often don’t challenge others who make it, despite studies by demographers that undercut the premise.

US News & World Report (2/18/21) quoted Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell’s claim that Biden’s proposed immigration reforms would create “huge new incentives for people to rush here illegally,” but the publication failed to present any alternative view. The Los Angeles Times (3/18/21) deferred in the same way to Sen. Lindsey Graham when the South Carolina Republican charged that legalization without increased border enforcement would “continue to incentivize the flow” of migrants.

LA Times (3/18/21): “As each side seeks to rally supporters and shape public opinion, the parties have pressed dueling narratives.”

Reporters often ignore a rather obvious problem with this argument: the fact that no legalization bill has been passed since 1986.

“Legalizing countless millions of illegal aliens—even discussing it—rings the bell for millions more to illegally enter the U.S. to await their green card,” Heritage Foundation researcher Lora Ries announced in January, according to New York Times reporter Miriam Jordan (1/27/21). The paper’s Nicholas Fandos (3/18/21) cited Rep. Tom McClintock, a California Republican, as claiming in March that a new legalization would mean border crossers “need only wait until the next amnesty.”

Apparently neither reporter thought to point out that based on past experience, the wait “until the next amnesty” could last as long as 35 years, nearly half a lifetime.

The center does not hold

What’s striking about corporate media’s immigration coverage is that conservative think tankers and Republican politicians so often get a platform, while the U.S. public hardly ever learns about immigration from the immigrants themselves (FAIR.org, 6/19/21).

Washington Post (10/7/21): “The journey starts with a calculation: What am I willing to sacrifice to reach the United States?”

There are important exceptions. Jordan’s January New York Times article failed to question the notion of “awaiting” the next amnesty, but it did include valuable reporting on migrants’ point of view. A recent Washington Post feature (10/7/21) by Arelis Hernández provided nuanced descriptions of the complex motives that have led Haitians to appear at the U.S. border. And the Vox explainer cited above is a good example of how the media can present a realistic picture of immigration patterns.

But there’s too little reporting of this caliber. The right wing goes all out; the center rarely provides the necessary balance. Coverage of the poverty and violence that actually drive migration—and the role of U.S. policies in creating them—appears in left media, as in a Jacobin piece (6/8/21) by Suyapa Portillo Villeda and Miguel Tinker Salas, but this sort of reporting is marginalized in corporate media.

The result is a public that’s primed to believe a Republican politician like Texas Sen. Ted Cruz when he casually distorts a lawsuit’s possible settlement into “@JoeBiden wants to give $450k to every illegal immigrant.”