In July, environmental activist Laiken Jordahl tweeted out a short video featuring what he called “the almighty border wall,” a section of fence at the Coronado National Forest in Arizona. The fence there includes several gates that need to be kept open at times of heavy rain. Without them, explained Jordahl, a staffer at Tucson’s Center for Biological Diversity, debris would accumulate behind the structure and floodwaters would eventually knock the wall down.

The gates were wide open. The only barrier was a few strands of barbed wire: anyone could easily have clipped the wire and walked through. No Border Patrol agents were in sight; neither were any would-be migrants.

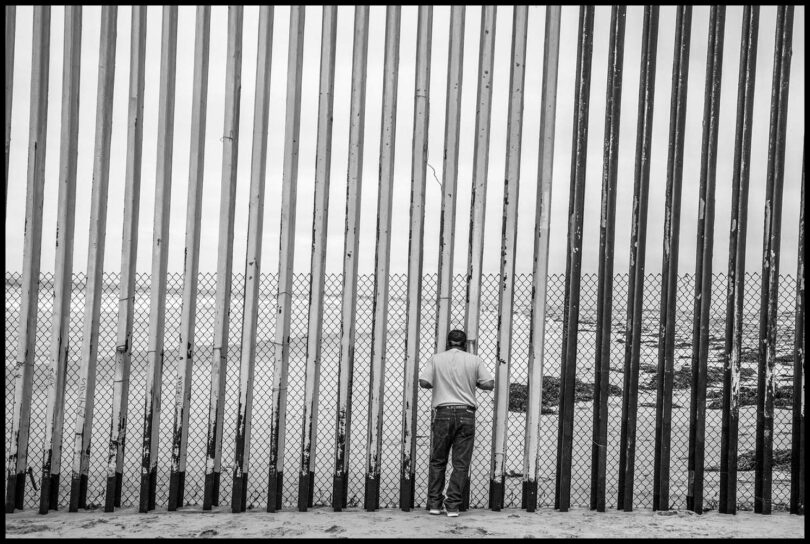

The border wall—built at a cost of up to $25 million per mile—“has never been anything other than political theater, other than a talking point, an election prop for the GOP,” Jordahl concluded in the video. “[T]hese walls were never designed to keep people out; they were designed to foment racism and vitriol and win elections.”

There’s another irony that the environmentalist could have noted: the taping of this idyllic scene took place after six months of media and political frenzy over a metaphorical “flood” of undocumented immigrants at the southwestern border, reportedly in response to a fictional Biden administration “open borders agenda.”

The differences from 2000

It’s true that apprehensions at the border have now reached at a 21-year high. According to Customs and Border Protection (CBP), fiscal 2021’s final number of migrants apprehended or encountered at the southwestern border was 1,734,686, higher than the 1,643,679 total apprehensions for fiscal 2000.

But the “border crisis” narrative ignores several important differences between 2000 and 2021—the number of successful border crossings, the legal situation of the migrants who arrive, and the impact of a global pandemic.

It’s true that less migrants were apprehended in 2000 as they tried to cross the border between ports of entry, but back then far more managed to cross without being caught than now—probably more than a million. Based on the Census Bureau’s annual American Community Survey (ACS), some demographers estimate that nearly 1.4 million unauthorized immigrants arrived in the country that year, with the great majority coming across the border with Mexico.

Other experts use CBP’s own apprehension rate metrics to make a much higher estimate: 2.1 million. (Details on these numbers are available in a four-part blog series starting here.)

Border Patrol agents now apprehend a much greater percentage of unauthorized crossers than they did two decades ago. The apprehension rate seems to have increased to about 80 percent, thanks in part to a massive increase in border security. If we apply this rate to the migrants encountered at the southwestern border in fiscal 2021, we come up with some 434,000 migrants crossing the border without being apprehended.

The government itself seems to have a lower estimate: anonymous CBP officials have told the Washington Post’s Nick Miroff that some 1,000 migrants were crossing each day without being apprehended—which would come to 365,000 for the fiscal year. Miroff apparently feels this reinforces the “border crisis” story, but in fact it indicates that just one-third as many migrants evaded the Border Patrol this year as in 2000.

Who is crossing the border?

But this year’s “crisis” has never really been about the border crossers who elude capture, despite inflated rhetoric about migrants “sneaking into the United States.” The main issue has been the migrants who were apprehended at the border and then allowed to enter the country.

These migrants are asylum seekers and unaccompanied children who cross the border and turn themselves over to Border Patrol agents to start the process of applying for asylum—a process established by the Refugee Act of 1980 and the Trafficking Victims Reauthorization Act of 2008. This sort of entry—unauthorized but legal—is another important difference from 2000: It was relatively uncommon then, but it started rising in 2014 and has now become a major factor at the southwestern border.

For fiscal 2021, CBP reports that 451,087 family unit members and 144,834 unaccompanied children were apprehended at the southwestern border. Not all these migrants get to stay in the United States, however. Asylum seekers are only admitted if they pass a credible fear interview, and even then, many are held in immigration detention, although the majority are conditionally paroled into the country. As for the unaccompanied minors, Mexican children are usually returned to Mexico; the other children are held by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) until it can arrange for them to join relatives or foster parents.

Of the 1,734,686 migrants encountered this year, less than a third, some 540,000, were actually admitted to the country, according to CPB expulsion and transfer statistics. Almost all were asylum seekers or unaccompanied children, and it’s important to remember this. They entered the country through processes established by law—a fact ignored in the rightwing rants about “illegals.”

The COVID effect

If we add these migrants to those who evaded the Border Patrol, we can estimate that between 905,000 and 974,000 border crossers entered the undocumented population this fiscal year. This is a high number, although not as high as the estimates for 2000. But what about the people who settle here each year by overstaying their nonimmigrant visas?

The 2008-2019 period was marked by a decline in the number of unauthorized border crossers, but little changed in the number of overstays. The result was that these migrants came to constitute as much as half or more of the people entering the unauthorized population during those years.

Overstays have now been radically reduced by the pandemic and its effects. COVID-related travel restrictions and consulate closings cut off the great majority of nonimmigrant visas for most of this fiscal year; the American Immigration Lawyers Association estimates an 80 percent drop in the number of visas issued. Based on the overstay rate in recent years, total overstays this year may be around 140,000, less than half the 306,000 estimated overstays in 2016.

It’s even conceivable that the increase in border crossings this year was partly a result of the drastic decrease in overstays.

2021 brought a striking increase in border crossers from regions other than Mexico and Central America—from as far away as India, China, and even Romania. This suggests that some asylum seekers who could have entered the United States with nonimmigrant visas in earlier years may have decided they had no choice this year but to attempt crossings at the border.

“Apocalypse” or “political theater”?

There’s one more difference between 2000 and this year: back then the mainstream media didn’t seem especially concerned about a “border crisis.” The New York Times even ran a July 2000 editorial entitled “A Quieter Immigration Debate.”

This isn’t to deny that that unauthorized migration to the United States increased somewhat this year, but it’s unclear why the change happened and whether it will be permanent. A perception—hardly justified—that the Biden administration welcomes immigrants could have played a role in this, although the effects of the pandemic and of climate change are likely to be more important. But the 2021 increase wasn’t significantly out of line with historic norms. Even if immigrants really were a problem, what happened on the border this year would hardly warrant former White House adviser Stephen Miller’s description of it as a “harrowing apocalypse.”

Laiken Jordahl’s video suggested that the border wall is really just “political theater.” The same goes for the “border crisis” narrative—like the wall, it’s full of holes.