This is a slightly revised version of a piece originally published in CovertAction Magazine on November 30, 2021. —Eds.

The working class explains and debunks common lies

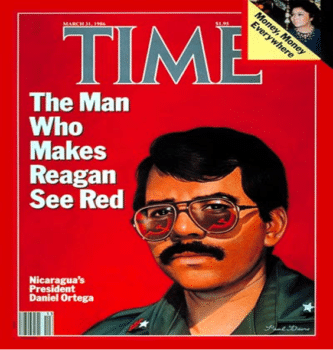

As predicted by multiple polls, Sandinistas, led by Daniel Ortega, won a resounding victory in the November 7th elections in Nicaragua. The elections were a referendum on the path that the Sandinista government has taken the country, a path grounded on large investments in social programs that have benefited people, especially the most disadvantaged, in every nook and cranny of the national territory.

Support for the reelection of the Sandinista government was astounding. Of the entire patron electoral (eligible voters), about 65% came out to vote and, of those, about 75.9% voted for the FLSN (Sandinista National Liberation Front) alliance ticket.

The victory of Sandinistas generated expected attacks, which seek to delegitimize the newly elected government in Nicaragua. The U.S., Canada, EU, OAS and their proxies–cynically claiming to be acting on behalf of the “Nicaraguan people”–seek to cripple the Sandinista government’s ability to provide for its population. The November 7th elections revealed the will of the Nicaraguan people, but because this will does not align with U.S. preferences, the elections are marred as “illegitimate,” a “sham,” and “authoritarian.”

Some of the Western imperial left, including academics and journalists, have joined the U.S. State Department to delegitimize the will of the Nicaraguan electorate and to manufacture consent against the Sandinista government.

These individuals legitimize the economic and political attack against Nicaragua. The burden of this aggression will be heaviest for the working class. Importantly, the mainstream media and the imperial left did not go on the ground to speak to farmers, union members, indigenous communities, or low-income Nicaraguans about the electoral process, their preferences, and the reason for those preferences. Worse yet, they ignored the multiple outlets that did just that.

None of these individuals parroting imperial propaganda decried the unjust detention of Steve Sweeny, a journalist and editor of the Morning Star Daily, Britain’s only socialist newspaper, who was prevented by Mexico from covering the Nicaraguan elections.

Instead, these stenographers condemned the electoral process from afar, portraying a dystopian world inside Nicaragua despite not providing a shred of on-the-ground evidence. A self-described “left” outlet, for example, would rather talk to clowns spewing right-wing imperialist talking points in Costa Rica than to working class people in Nicaragua, whose opinion they have ignored and suppressed in their coverage.

Unlike these propagandists, I spoke to Nicaraguan factory workers, domestic workers, stay-at-home mothers, truck drivers, farmers, and community leaders in the outskirts of the city of Estelí, where international electoral companions observed a free and fair election. I sought the opinions of Sandinistas and those who do not identify as such to understand electoral results.

Below, I document the reasons why the Sandinista government enjoys support from the majority of the electorate as well as some grievances some sectors of the population wish the government would address. The platitude-, lie-, and interventionist-filled propaganda from Western media, the imperial left, and interventionist governments do not come close to providing an accurate picture of Nicaragua, its culture, or its popular will–or explaining the resounding Sandinista electoral win.

Abstentions: The Case of Esteban

I spoke to Esteban (all names are pseudonyms) on the eve of the elections. Esteban is not a Sandinista—by a long shot. He is a sort of jack-of-all-trades handyman. He is a blue-collar worker who does not support the Sandinista government. Esteban’s main grievance is, he argues, that Nicaraguans pay too much taxes. This concern was startling to me, because he does not pay into the IR system—a 15% income tax.

He suggests that income taxes should be capped at 7%. When I asked him about government projects that taxes help fund, he acknowledged them. He acknowledged, too, that these projects are beneficial to the population, but, each time, he articulated something wrong with them. For example, Esteban suggests that people who do not use public services, like hospitals, should not pay for them.

He does not argue that Nicaraguans should not have public hospitals. In fact, I was surprised at his defense of a public system. Esteban argued we should have a public system, but that it is unfair for those who do not use it to pay for it. He had an accident recently and had major surgery in Nicaragua at no cost in a public hospital. His perspective reminded me of the “all-government-is-bad” opinion in some sectors of the rightwing in the United States. Importantly, he did not vote.

What Can We Learn from Esteban? Myth and Reality about Abstentions

I begin with Esteban because one of the attacks against the legitimacy of the Sandinista electoral victory is that there was massive abstention due to political repression. This is demonstrably false. Esteban did not tell me that he feared political repression for his views, which he articulated loudly and proudly; political repression did not figure into his decision not to vote.

His abstention stemmed from his worldview about governments more generally, especially one whose politics prioritize investment in the public sphere for which communal sacrifices are shared.

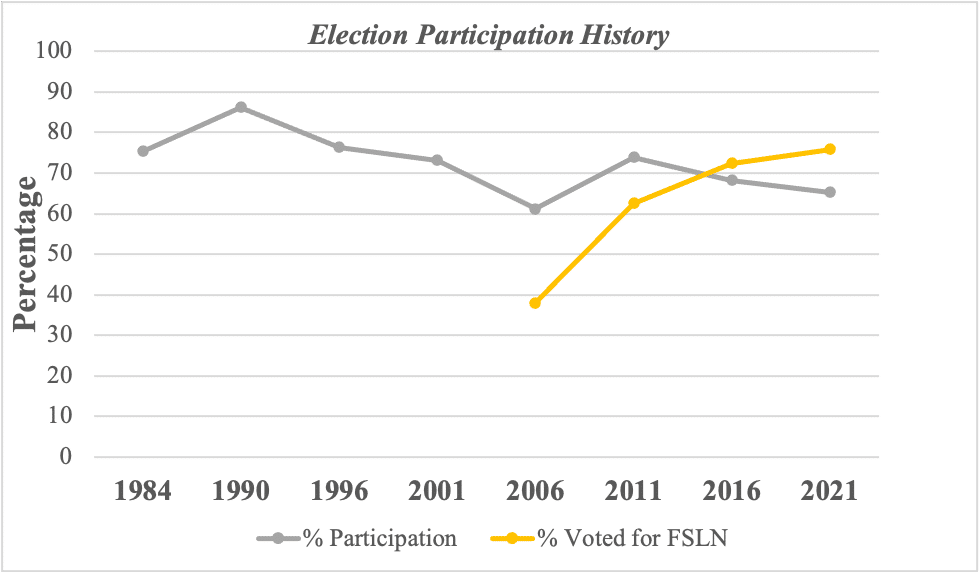

Furthermore, abstention in this election cycle was not widespread, as the US-backed opposition had hoped and called for. In the figure below, I chart election participation history in Nicaragua since 1984, including the percentage of those who ended up voting (% participation) and, out of those who participated, the percentage who voted for the FSLN. Percent of participation has been rather stable since the FSLN returned to power in 2006—between a low of 61% (in 2006) and a high of 73% (in 2011)—after a steady decline in participation during the neoliberal period (1990-2006).

In this election cycle, the percentage participating was 65%. The chart also shows that percentage support for the FSLN has been increasing since their return to power.

The 80% abstention rate that some in the mainstream media and imperial left are repeating is a baseless lie. Ben Norton looked into the one organization that has made up the “80%” abstention statistic: Urnas Abiertas. He thoroughly documents its unseriousness, but, more importantly, its links to the U.S.-funded opposition, part of a larger regime change effort directed against the FSLN.

For example, he documents that the only two people who have been publicly identified with this organization are “both partisan right-wing activists who work in the Western government-funded nonprofit-industrial complex, without any technical background or experience in election monitoring.” Organizations like this pop up to provide their regime-change operations a veneer of independence and credibility.

“Soft” Support for the Sandinista Government

Carlos is a driver by trade. Yuniel and Joel are factory workers. Before my conversation about the elections with them, I rarely heard them say much about politics. The few things that I had heard were criticisms. I really wanted to understand their perspective because I thought they would be in favor of the opposition.

I was wrong.

Yuniel is primarily concerned with taxes. He informs me that his salary is not enough; therefore, he is upset that he has to pay income taxes from it. He deems it unfair having to pay more taxes if he earns more (in absolute terms, because the rate is fixed). It seemed to me that Yuniel was unclear as to what the taxes are used for, which may explain part of his frustration. Carlos is a sub-contractor for a government-funded infrastructure project. He stated that the Sandinista government has done both good things and things he has disagreed with. Carlos says he mostly keeps his opinions to himself because he works with different kinds of people with varying political views.

He describes his job and pay as good, a consequence of infrastructure investments from the government. He is afraid that a new (opposition) president would not invest as much in infrastructure, which would decrease jobs and other economic activities. Joel, finally, does not say much. On the eve of the election, Joel said that the president had done good things. He said it as if to say, we have to admit it. Like Carlos, he also said that if another person wins the presidency, this new president will invest less.

Yuniel, Carlos, and Joel, despite disagreements with the Sandinista government, support the re-election of Daniel Ortega because any other individual–from an opposition party–would not invest as much in the country.

Yuniel, Carlos, and Joel, despite disagreements with the Sandinista government, support the re-election of Daniel Ortega because any other individual–from an opposition party–would not invest as much in the country.

“Soft” Support for Sandinismo and Its Dynamics Across Nicaragua

Yuniel, Carlos and Joel exemplify what some characterize as “soft support” for the FSLN. The opposition (inside and outside the country) hopes to remove Ortega to decapitate and neutralize Sandinismo. To do so, a key propaganda strategy of the opposition, especially the U.S.-funded faction and interventionists abroad, is to demonize Daniel Ortega–and his family.

This strategy has not been successful. Yuniel, Carlos, and Joel acknowledged that the Sandinista government has invested in broad-reaching social programs and public infrastructure. President Ortega, they said, has accomplished “good things,” whereas a new president will steal without investing in the country. Government projects will not occur with an opposition-led administration. The support for public health, in particular, is palpable. I asked Carlos what would happen if any government tried to privatized the health system. Immediately, he replied, that it would not happen. He argued that Nicaraguans would rise up in defiance against such a move. In short, despite vague criticism, all three supported the re-election of Daniel Ortega and the Sandinista government.

Although it was my impression that Yuniel was the least likely to vote for the continuation of the Sandinista government (if voting at all) on election day, he revealed that he voted for the FSLN alliance ticket.

Further, “soft support” partly explains why the FSLN achieved a remarkable 75.9% support among Nicaraguan voters. The journalist William Grigsby points out that there were municipalities in which Daniel Ortega received more votes than there are registered Sandinistas. This dynamic occurred, for example, in six out of eight municipalities of Caribe Sur, including Paiwas, La Desenbocadura de Rio Grande, Corn Island, and Pearl Lagoon. Even non-Sandinistas, Grigsby shows, voted for Daniel Ortega across the country.

One of my respondents, Fanor (see below), referred to this phenomenon as voto progreso–a vote that recognizes the social progress that the Sandinista government has accomplished for Nicaragua and signals desire for its continuation.

Voto ideológico, on the other hand, is a vote for the FSLN that is not only rooted in support of the socialist-oriented policies of the Sandinista government, but one that recognizes the importance of the FSLN as a revolutionary project against imperialism whose significance in and out of Nicaragua lies in providing an alternative to the “savage” capitalism that the U.S. wants to impose on the country–and the world. In the latest credible poll before the election, the expected “voto suave” (soft vote) constituted 17.4% support for the FSLN.

Voto ideológico, on the other hand, is a vote for the FSLN that is not only rooted in support of the socialist-oriented policies of the Sandinista government, but one that recognizes the importance of the FSLN as a revolutionary project against imperialism whose significance in and out of Nicaragua lies in providing an alternative to the “savage” capitalism that the U.S. wants to impose on the country–and the world. In the latest credible poll before the election, the expected “voto suave” (soft vote) constituted 17.4% support for the FSLN.

In addition to the soft vote, support from those who “tend to vote” for the FSLN (4.5%) and those who strongly support the FSLN (voto duro, 53.4%) add up to the expected more than 70% support for the FSLN in the elections. The FSLN eventually attained 75.9% of the vote on Nov. 7th.

Yuniel, Carlos, and Joel are part of the “soft” support that materialized for the FSLN. Even those who have disagreements with the government, cannot deny–and, in fact, defend–socialist policies that have benefited all of Nicaraguan society.

Falsehoods From the U.S.-backed Opposition

To provide ammunition for those who seek to delegitimize the Sandinista government, the CID-Gallup (not part of the internationally known Gallup) completed a poll on behalf of the opposition that presented widely inaccurate predictions. Unlike the M&R Consultores, which had completed a number of polls across Nicaragua in the months leading up to the election, the single CID-Gallup poll stated that only 19% of the population supported Daniel Ortega.

This poll ignores over 2 million card-carrying Sandinistas in the country and votes from individuals like Yuniel, Carlos, and Joel. The implausible CID-Gallup poll, which has been criticized for its methodology, does not accurately capture “hard” support and totally ignores “soft” support.

None of the people with whom I spoke expressed support for the U.S.-funded opposition members currently detained. The U.S.-funded opposition is lionized by the West outside of Nicaragua. Inside the country, they are largely ignored.

Even if the U.S.-funded opposition had participated in the elections, it wouldn’t have made any difference in the outcome; this faction of the opposition does not have much support in the country, perhaps only among the (very tiny) upper class.

Reporters have documented their political irrelevance. None my interviewees–not even Esteban–told me they would have voted for any of the people currently in jail, whom the mainstream media and imperial leftists–untethered from reality–call “pre-presidential candidates,” “presidential hopefuls,” or more recently “presidential candidates.” No matter how many times this lie is debunked, it re-appears like a regime change zombie.

Why Does the U.S.-backed Opposition Have So Little Support?

To understand why the U.S.-funded opposition has so little support, we have to remember at least two things. First, the U.S.-funded opposition never coalesced around a single candidate.

Hunger for power fueled infighting and prevented a viable opposition coalition. They only share hatred towards Sandinismo and reliance on U.S. funding.

Frustrated, the U.S. (including its embassy in Nicaragua) was working on getting everyone behind Cristiana Chamorro (to the chagrin of others in the opposition). She was being groomed to be the Nicaraguan Guaidó. Video of a meeting with U.S. officials and their lackeys show how giddy regime changers were about her placement (not election!) in power, repeatedly calling her “President Chamorro.”

The Sandinista government dismantled this plan, which unraveled after her corruption was exposed and she was subsequently placed under house arrest.

The second issue is even more important. The U.S.-funded opposition in jail (and abroad) is intimately associated with the 2018 deadly barricades and subsequent havoc they wreaked on the country. For this reason, even those who disagree with some aspects of the Sandinista government are not turning to the U.S.-funded opposition, nor do they care about their detention.

The U.S.-backed 2018 coup d’état attempt was detrimental to most people in the country. There is no support for another violent clash, as the attempted 2018 coup d’état inflicted economic, psychological, and social devastation on most of the society, especially the most disadvantaged.

Scene from the violent 2018 U.S.-backed coup d’état attempt against the Nicaraguan government. (Source: nytimes.com)

For example, in total, the estimated economic loss due to the coup is about $24,000 million dollars, which include $206.5 million dollars’ worth of damage to local and national governmental institutions, the collapse of 8,708 small businesses, and loss of 119,000 jobs. The last thing Nicaraguans want is violence in their communities, after having lived through the barricades in 2018 that destroyed their household economy, regardless of their political leanings. I was in Nicaragua at the time. Only those who lived through it can understand the attempted coup’s horror.

According to Danto, a campesino who works the land for a living, only the upper class, especially members of the COSEP (Nicaragua’s powerful chamber of commerce), want another revuelta (violent clash), because they are able to weather its associated economic storm and will eventually recoup losses (should they suffer any). COSEP loudly supported the 2018 coup d’état attempt.

Had it succeeded, members of the COSEP would have wielded more political and economic power, hoarding even more wealth away from the Nicaraguan people. (In an opposition newspaper in Nicaragua, which is the voice of the upper-class opposition, there are renewed calls for another revuelta.)

Rejection to violence was loud and clear across the country on election day. As of this writing, not a single violent incident has been documented at polling places on what turned out to be a peaceful election day. Thus, it is not true that Daniel Ortega won re-election because some members of the currently-detained U.S.-backed opposition did not participate. Nicaraguans do not want what they have to offer.

A Final Lesson from “Soft” Supporters of the Sandinista Government

Yuniel, Carlos, Joel, and Esteban all articulate something else: Health care is a fundamental right and should be provided for free. This idea is now entrenched in Nicaraguan society, after fourteen years of the second phase of the Sandinista revolution.

Nicaraguans have come to expect public and free access to medical care. Support for the idea that education should be a fundamental right is also prevalent. Should anyone try to privatize these services, they will find considerable resistance. Privatization efforts, especially of public services, will face stiff resistance, even among non-Sandinistas. This is because public access to these services benefits most of the society.

Nicaraguans do not spend anywhere near in health care what people do in the U.S. Even some right-wing Nicaraguans who have gained green cards, or who have been naturalized in the United States and are doing well economically take care of their medical needs in free and public hospitals in Nicaragua, given how expensive it is in the United States (while railing against the Sandinista government that provides it).

The “Hard Vote” and a Winning Strategy

Virna, Juliana, and Fanor are part of the “hard vote” and the heart of the Sandinista revolution victory at the polls. All three are leaders in their respective communities. They are all active members of the FSLN.

Virna, a domestic worker with kids, comes from a family of Sandinistas. She sees her militancy as a family legacy that must endure. She supports Daniel Ortega and his government because, above all, he looks out for the poor. Everyone whom I interviewed who identified as Sandinista (whether or not they were directly involved in politics) said this, over and over again. The Sandinista government, they repeated, cares about the most disadvantaged.

Virna explained to me that the FSLN had been organizing and were prepared to win this election. As a leader, part of her responsibilities included finding people to help at the polls; she also made sure they had what they needed (including coffee) and that they were safe, though she did not work the polls (because she is a local leader for the FSLN—it is against the rules).

She and her colleagues arranged transportation for the elderly and disabled people who wanted to vote but had no means of getting to the polls. Virna was not worried about the FSLN losing the election, because, as she argues, there have been so many benefits for the population, including public and free health care, that it is inconceivable for most of the population to want to put a break on those services. Fanor agreed.

Fanor, a younger local leader, told me that FSLN’s winning strategy was simple: acompañamiento a las familias (to accompany families) to help address their needs. For some time now, the FSLN has been working to make sure that, as he says, the Sandinista government has a strong and constant presence within households, not just during election time.

Fanor listed a range of services and programs from the Sandinista government that he has helped deliver, including helping elderly with wheelchairs, providing food to those in need, Plan Techo (giving roofing material to disadvantaged households), community cleaning, cemetery upkeep, defraying costs associated with funeral services, disseminating information about vaccination, building communal homes, providing access to clean water, Bono Productivo (through which women are given pigs, chickens, and cows to stimulate household food sovereignty and economic subsistence), and others.

These local activities, he argues, constitute one type of help the FSLN provides to families. The FSLN, he says, is working on a range of other projects to spur economic growth and to build on food sovereignty. He notes that the FSLN is not relying on big business to spur economic growth. They are working on economic self-sufficiency, prioritizing small and medium businesses and enterprises. His comments are supported by the data.

The Sandinista government’s incentives for a “people’s economy”—one that primarily relies on production from families, communities, cooperatives and associations (small and medium producers/enterprises)—have grown dramatically since the attempted 2018 coup d’état. Although the Sandinista government had been supporting a people’s economy prior to the coup, the reliance on the capitalist class for wealth generation was higher prior to the 2018 coup d’état attempt than it has been subsequently.

Fanor also explained to me that home visits are key to the FSLN’s strategy because community members often do not air all of their grievances in public forums. But in the privacy of their homes, they are more forthcoming about issues they would like addressed in their communities.

As such, he and other people serve as conduits between community members—of all political stripes—and their local FSLN governments. Importantly, the services that Fanor and his associates help deliver are distributed Parejo—to everyone, irrespective of political affiliation. Juliana, a stay-at-home mother and FSLN community leader, underscored this point.

Juliana, who takes care of a family member, told me that, as a FSLN community leader, she sees her work as providing for her community and delivering government assistance to all who need it, regardless of political leaning. She started working with the FSLN after being inspired by the Sandinista takeover of Managua in 1979.

Her mother also has a long history of supporting Sandinistas. Juliana reached her leadership position due to internationally recognized gender equality efforts from the FSLN, for which Nicaragua ranks, in 2021, #1 in the Americas. She notes that before the FSLN returned to power, there were few, if any, benefits from the government.

Since 2007, she has worked on helping deliver a range of projects to her community. Recently, she helped shepherd an electricity project for her town. Sandinistas and non-Sandinistas benefited from this and other projects in which she has been involved, including Plan Techo. She notes that even “liberales”—a term used for people who support some faction of the opposition–can see what the government has accomplished for them. She even notes that some Sandinistas get upset because liberales are given jobs at governmental institutions and use these posts to rail against—and undermine—the revolutionary Sandinista project.

All three expected the FSLN to win, describing peaceful free and fair elections in their respective communities. Juliana told me that most people in her community came out to vote in the afternoon after church. She informed me that because a faction of the opposition had called for a no vote, at least one bus company who supported the opposition did not offer its services that Sunday. This had a negligible impact on participation because voting locations were widely available. People drove, walked, or got rides to their voting centers.

Rank-and-file Sandinistas

I also spoke to Helena, Danto, and Tamo. These individuals support Sandinistas, and Helena and Danto identify as such. I did not ask Tamo if he did as well, though it would be surprising if he didn’t identify as Sandinista. All three noted the importance of voting.

Danto recalled that during the Somoza dictatorship, in his town, the vote was bought and paid for with 5 córdobas, a nacatamal (a local dish), and un trago (alcohol). Sandinistas changed all of that, he said. Sandinistas supported the most vulnerable citizens with literacy campaigns, social rights, a legitimate legal authority, and the reduction of corruption in government.

He noted, with confidence, that because Sandinismo advocates for the poor and Sandinistas are well organized, it will be hard to topple the Sandinista government. Helena, along similar lines, argues that the Sandinista government has provided hospitals, schools, housing, and social security benefits to Nicaraguans. In the neoliberal years, she said, they did not get any of that.

A family member of hers received the Bono Productivo and has been trained to work the land to support household economic independence and food sovereignty. She told me that Sandinistas will be in power as long as they have popular support. Ana, an elderly woman, told me that Sandinistas are people of good conscience. Daniel Ortega, in particular, is a good man, she says, who helps those most in need. Reverence for El Comandante (Ortega) has been documented elsewhere. During the Somoza dictatorship, she did not vote, but has voted Sandinista ever since the triumph of the revolution.

Of all the people I spoke to, I gathered that Tamo has the least material resources. He works as a cuidandero, or someone who is hired to live on someone else’s land to work it and protect it so that its harvest is not stolen from its owner. Tamo is shy but agreed to speak with me about the forthcoming elections. He had never been interviewed before (like on TV, he said).

He mentioned the new hospitals, but spent more time talking about the roads that the Sandinista government has built and fixed over the last 14 years in the town he hails from—far away from where he works. The roads, he says, have made a big difference to people in his town, who can now move their “commodities” with ease and sell them elsewhere.

He had been planning to go back to his hometown to vote, but, due to his job, he was not able to vote. In addition to Danto, Sandinistas who left for the U.S. were not able to vote during this election cycle. As Juliana notes, support for the re-election of Daniel Ortega and the Sandinista government would have been higher had all those people been able to vote.

The Attempted 2018 U.S.-backed Coup D’état: Its Role in the Electoral Win of the FSLN Alliance Ticket

Virna, Juliana, and Fanor all agree that the FSLN is more organized now than it was prior to the attempted U.S.-backed coup d’état in 2018, which, for each of them, was quite difficult to live through. Fanor noted that he was targeted through social media.

Although Fanor was disappointed by some young people in his generation who initially bought the U.S.-backed propaganda, he and others worked with families during the attempted coup to make sure their family members did not join the deadly barricades so as to avoid a tragedy, which would have divided the community. Not a lot of people in his community, he says, got involved in the coup. During the attempted coup and after, he and his comrades worked to debunk the various lies from the U.S.-funded opposition.

Fanor tells me that he knew the attempted coup was not going to work because he saw, firsthand, how much families were suffering economically as a result of the revuelta, which prevented them from getting to and from work, from reaching hospitals, or from completing other necessary tasks. Thousands of small family businesses collapsed. Fanor saw how angry community members were about the devastation.

Virna was the subject of attacks and insults from her neighbors. She was surprised because she had been working in her community by providing help and shepherding projects for everyone, regardless of their political affiliation. There was a point at the height of the violence that she thought about resigning from her post as FSLN community leader out of fear, but she decided to remain steadfast in her work.

Compañeros protected and took care of her because she is well known for her community leadership. They were afraid that she was being targeted for an attack, which were rampant against Sandinistas all over the country.

Sandinistas were subjected to insults, beatings, torture, burnings, and killings. Some had their property vandalized or destroyed. Virna spoke heartbreakingly about how difficult it was to endure during the 2018 coup attempt. She used to cry, she says, every time someone was killed, including a young man from her community who was shot in the back by opposition mercenaries. Her story underscores the importance of women in the resistance to the attempted 2018 coup d’état.

Juliana relayed similar fears during the attempted coup due to her leadership in the community. She did not go to the city because she feared the barricades. Juliana was afraid she would be recognized as Sandinista and targeted. She was petrified of walking to her job because opposition mercenaries manning the barricades would sometimes pass by on her way to work.

Working hard to assure an FSLN electoral win is one way, Juliana and others argue, to prevent the rise of a new violent coup.

Despite a mountain of evidence that the 2018 violence was a consequence of a U.S.-backed coup attempt, Western media and imperial left \refuse to recognize it. In doing so, they obscure, ignore, and erase the suffering and targeting of Sandinistas, who were the victims of U.S. aggression through local proxies. Anyone who refuses to acknowledge this fact will not understand FSLN’s subsequent organization, priorities, and eventual win at the ballot box.

Conclusion

In speaking to regular working people in Nicaragua, I found overwhelming commitment to the second phase of the Sandinista revolution, even among those who expressed some disagreements with the Sandinista government and constantly consume anti-Sandinista propaganda through social and other opposition media.

For Sandinistas and non-Sandinistas alike, the achievements of the Sandinista government since returning to power in 2007 cannot be denied. Moreover, the second phase of the Sandinista revolution has helped change Nicaraguan society, such that people across the political spectrum think of their public services as rights that should not be privatized— rights they are prepared to defend.

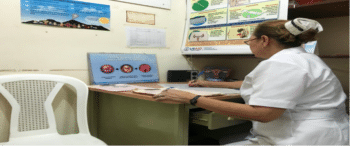

This is particularly important when it comes to healthcare. Investments in health, including infrastructure and programming, have garnered plenty of support for the Sandinista government. Recently, the Ministry of Health started vaccinating people for COVID at home who, for whatever reason, are unable to attend a health center but would like to be vaccinated.

Western mainstream media and imperial leftists ignore the voices and perspectives of working-class people, like those I interviewed, because they do not conform to the U.S. and their proxies’ narratives. Importantly, my respondents’ views do not conform to the narratives that members of the now-defunct MRS feeds the imperial left in the U.S.

U.S. State Department cables published by Wikileaks show that leaders of the MRS are U.S. informants. They have publicly lobbied for economic warfare against their own country. Yet these individuals present themselves as leftists to an international audience, obscuring their support for the Nicaraguan rightwing and the goals of U.S. empire in Nicaragua.

Disturbingly, the imperial left takes the vitriol of the MRS members as the voice of the Nicaraguan people and ignore the perspectives of people like those I highlight here. When imperial leftists write and speak on behalf of “the Nicaraguan people,” they mean to say “my friends from the MRS and other members of the Nicaraguan upper class.”

The importance of the social class dimension in understanding the Sandinista win at the ballot box cannot be overstated. The FSLN won because it has the support of the working class.

Although they are the majority, their perspective is largely ignored by the Western mainstream media and the imperial left. By contrast, the perspective of the Nicaraguan upper class–especially its elites who live off of U.S. funds, which largely pay for anti-Sandinista propaganda–is magnified and prioritized the Western world over. For this reason, I did not speak to members of the Nicaraguan upper class.

Note on the Term “Imperial Left”

I use the term “imperial left” following Vijay Prashad’s retort to David Harvey: You live on the other side of imperialism. I say the same thing to leftists in the imperial core, who, whatever their intentions, refuse to acknowledge Nicaraguan sovereignty and have bent themselves into a pretzel trying to justify their alignment with the U.S. State Department’s regime change efforts. Instead of listening to working-class Nicaraguans as I have done here, they pontificate, presuming to speak on behalf of Nicaraguans, judging what they don’t know, including how socialist the socialist-oriented Sandinista government really is.

This an old habit of the imperial left. Why can’t they understand that only Nicaraguans get to decide whether the Sandinista government is committed to their revolutionary aspirations, whether it’s socialist enough, and whether it is worth supporting? It is easy to point the finger at a developing country for its imperfect revolution. It would be much harder to oppose empire and work on building a socialist-oriented project in the United States by listening to and learning from working-class Nicaraguans who engage in building this political project every day.

Do not believe them when they tell you the left is divided. There is no division. The (anti-imperialist) Left is standing with the Sandinista victory in Nicaragua. The rest are either confused or advocating an imperialist political project.

I urge the imperial left to join calls that reject any and all U.S. intervention in Nicaraguan society, even if their Nicaraguan friends want otherwise. The imperial left will not suffer the consequences of U.S, EU, and OAS aggression, which will only generate economic suffering and political conflict for and among Nicaraguans, especially the most vulnerable. Esteban, Carlos, Yuniel, Joel, Fanor, Danto, Juliana, Virna, and Helena will suffer from U.S. aggression, not you.

U.S. unilateral coercive measures against Nicaragua will increase its population’s economic pain and will force more people to migrate to the U.S. in search of economic sustenance. The histrionic response from the U.S. to the Sandinista electoral victory has led some Nicaraguans to believe that the United States will accept all Nicaraguan migrants. Political aggression from the U.S. coupled with economic difficulties that stem from sanctions will increase Nicaraguan migration to the United States. Migration is the harvest of empire.

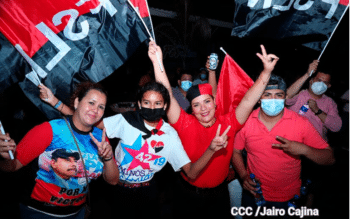

The 232 international companions from 27 countries observed peaceful, fair, and democratic elections in Nicaragua. Celebrations erupted all over the country once results were announced.

The FSLN will visit with communities to hear their grievances, needs, and desires. Elected members of the National Assembly will participate in this effort, which is meant to bolster the FSLN’s bold plan to reduce poverty and increase well-being for all Nicaraguans. As William Grigsby argues, in the next few years Nicaragua will begin to reap what the Sandinista government has been sowing for 14 years—a great leap forward is coming.

Sandinistas are far from done with their revolutionary project.