‘You need to read Archie’, Vincent Harding told me one sunny day in 1988 in Claremont, California. A veteran civil rights activist, Harding had worked closely with Martin Luther King, Jr., including authoring King’s key anti-war speech, ‘A Time to Break the Silence’. The previous year, I had read Harding’s remarkable book There is a River: The Black Struggle for Freedom in America (1981), a book that caught the sway of the movement, the ‘black river of struggle’. Harding was in Claremont to speak at a conference my teachers Sid Lemelle and Ruthie Gilmore had organised on pan-Africanism. That conference helped shape most of my intellectual world. Many of the papers did not yet make sense to me, but conversations at the tea break with Maryse Conde, Paul Gilroy, Robin Kelley, Cedric Robinson, Ann Seidman, Ntongela Masilela, and members of the African National Congress (ANC) and the South-West Africa People’s Organisation (Swapo) stirred in me a great desire to swim in that river of struggle. But why was Vincent Harding talking to me about Archie?

It was hard to be on a college campus in the United States during the 1980s and be indifferent to three kinds of struggles: the emergence of multiculturalism, the harsh wars of Central America driven by the United States government, and the struggles of the southern African people for liberation. My dorm room in college was spartan except for two poorly produced posters: one a stencil of the iconic picture of Hector Pieterson being carried by Mbuyisa Makhubo in Soweto (June 1976) and the other a Palestinian Liberation Organization poster of a house with the shadow of an Israeli soldier against blood pouring through the door to depict the atrocity of Sabra and Shatila (1982). These were my early commitments against occupation and for liberation that remain as strong now as they were then. That was the reason why I had taken classes with Sid Lemelle on African history, it was why I was involved with the organisation of the pan-African conference, and it was why Vincent Harding told me about Archie.

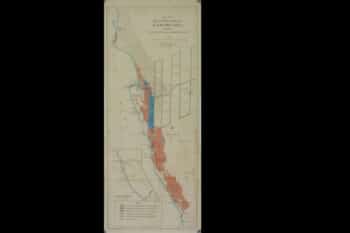

The Claremont library had none of Archie’s books, which was not a surprise. The library at Pomona College was named after William L Honnold, who made his money in South Africa from the colonial mining industry (as I found out many years later from Archie’s student, John Higginson, who had previously taught at Pomona and ran afoul of the administration because of his investigation into Honnold’s past in southern Africa). In 1921, the Consolidated Diamond Mines of South-West Africa, founded by Ernest Oppenheimer sent Honnold off to what would later be Namibia to scout for diamonds. Honnold worked for Oppenheimer’s Anglo-American Corporation of South Africa, where he made his fortune. That money built the library at Pomona which had a meagre collection of anti-imperialist writings (certainly none of the books by Archie).

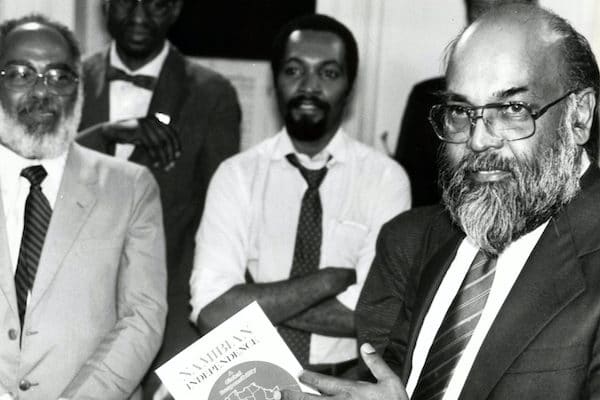

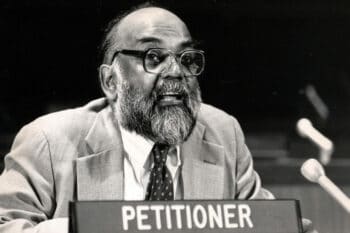

Sid Lemelle gave me two books to read, Namibian Independence and Non-Alignment in an Age of Alignments by Archie Singham and Shirley Hune, both published in 1986. I devoured them, particularly the book on Namibia, which is only a hundred pages long. That book made the case for the independence of South-West Africa–where Honnold had gone to scout for diamonds. Archie, or AW Singham, was the representative of Swapo in the United States.

Archie wrote from that perspective, as an l’intellectuel engagé, deeply committed to the truth of liberation and therefore to the primary agency of that liberation, which was Swapo. Swapo, Singham and Hune wrote, ‘is self-consciously a multitribal and nonracial organisation with an international perspective’, well-aware, as they put it, that ‘tribalism and communalism can destroy a nation after independence’. Since Swapo stood for all Namibians, it was only just that the South African apartheid regime–itself illegitimate–negotiate with Swapo for Namibia’s independence as it faced Swapo fighters on the battlefield. This was the brunt of their case for Swapo: it was the authentic political instrument of the people, and it would eventually defeat apartheid South Africa on the battlefield and in the negotiating rooms. ‘Today’, they wrote in 1986, ‘the world is faced with the obscenity of an illegitimate regime in the southern half of the African continent which has plundered the resources of the African people and used these resources to conduct a war of genocide against the peoples of southern Africa’.

These were strong words. They appealed to me, since I saw the same kind of obscenity in the Reagan administration as it rained terror on the peoples of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Nicaragua, and as it tried to throttle the Cuban Revolution. It was impossible to sit quietly in a library named for a man who had plundered southern Africa and tolerate the acts of his government to assist the racist regime in southern Africa. The frankness of Archie’s writings struck me like a gale-force wind. You could say the truth and you could stand unflinchingly alongside the political forces of those who wanted to establish justice in the world.

It is never easy to build a new world. The old world that we inherit is ugly, and its ugliness creeps into our own sensibility. We want revenge for the ills of the past and we reproduce–often unwittingly–the hierarchies that we abhor. These things had been revealed to me already by Frantz Fanon’s Wretched of the Earth (1961), a sublime book, a surreal book, dictated by a dying Fanon in Tunis over the course of several weeks. Political formations are rarely built on an empty slate. They emerge on older traditions, and they must draw together people with a range of views that are never identical. Swapo had a clear Marxist approach at that time, but it had to appeal to allies who were nationalists of a different kind (in fact, Singham and Hune dedicated Namibian Independence to Indira Gandhi, who had been assassinated in 1984, and who had been the chair of the NAM in 1983).

In December 1960, this width of Third World nationalism had pushed a strong resolution in the United Nations General Assembly called the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples. This Declaration had a stirring line that speaks to us over the decades: the process of liberation is irresistible and irreversible. It was the anchor of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), set up in September 1961 in Belgrade. Namibian Independence was written almost as a submission to the NAM for that body of 101 members of the Third World to act as a bloc against the wretched support of the West for apartheid South Africa. It was part of a process to guide the motion of history, building alliances, building confidence, trying to build a positive process.

Not many people today pay attention to the Non-Aligned Movement, which had its 18th summit in Baku (Azerbaijan) in 2019 and will have its 19th summit in Kampala (Uganda) in 2023. But when the NAM was created in 1961–originally with 25 members–it was an enormously important initiative that developed out of the Bandung Conference of 1955. The NAM’s position against nuclear confrontation and its strong views on inequality between nations because of colonialism shaped the arguments of the mid-century till the fall of the USSR in 1991. It was thanks to the NAM that the UN had to build the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) in 1964 and it was thanks to the NAM that the U.S. and the USSR had to begin negotiations on the cold war. By 1988, when I picked up Singham and Hune’s book on the NAM, it was already being disparaged by the Western powers as a futile project, as futile as the entire Third World Project to build the sovereignty of the countries of Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Globalisation was the watchword, which meant a surrender to the major multinational corporations and to the imperialist powers. The war on Iraq (1991) and the establishment of the World Trade Organization (1994) were specimens of this new era.

In 1983, the population of sovereign Grenada was 96 000 (it was the subject of Archie’s 1968 monograph, The Hero and the Crowd in a Colonial Polity). The U.S. invasion of Grenada in October that year was by itself not novel since the United States had a long history of military interventions. But there was something particularly sinister about the invasion of Grenada. In their book on the NAM, Singham and Hune write of how this invasion took place in total violation of the UN Charter (1945) but in accord with the doctrine of ‘linkage’ developed by the U.S. war planners; linkage referred to the view that any national liberation struggle could not be non-aligned but had to be part of a global communist conspiracy, and therefore had to be destroyed. A preview of this use of the linkage doctrine was in Afghanistan, when the U.S.–along with Saudi Arabia and Pakistan–built up the counter-revolutionary reactionaries who would become the mujahideen to attack independent Afghanistan after the left seized power in the Saur Revolution of 1978. Grenada joined the NAM in 1979, after the national liberation New Jewel movement came to power on the island, and at the 1983 NAM meeting–just a few months before the invasion–Grenada was the Vice Chair for Latin America. That U.S. invasion was a punishment, part of the U.S. assault on any Third World state that tried to assert itself. It was a punishment with the hard edge of racism intact, the sensibility of the colonising countries that they must always be the ones to rule and cannot tolerate the assertion of the formerly colonised.

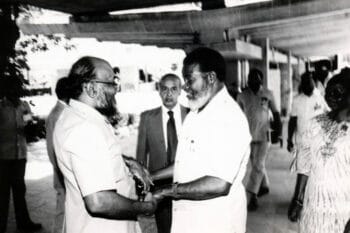

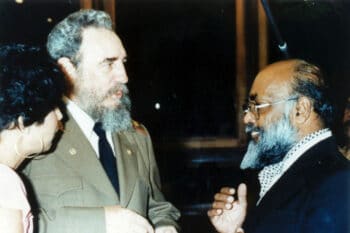

Years later, when I first saw Archie speak at an event organised by The Nation in New York (just before he died in 1991 of late diagnosed cancer), I reflected on what Vincent Harding had said. Perhaps he thought about Archie because he was from Sri Lanka, and I am from India; two South Asians with deep commitments to social revolution in Africa and in Latin America. Born in Burma in 1932 to parents from Sri Lanka, Archie certainly lived a peripatetic life teaching at the University of the West Indies in Jamaica and then at Howard University, sitting in a room with Fidel Castro and Kenneth Kaunda and then arguing with his close friend CLR James about race and class. Victor Wallis later wrote of Archie that he ‘had never known anyone who had such thoroughly grounded anti-imperialist convictions and at the same time such an easy familiarity with both the theories and the practitioners of mainstream social science’.

Archie was one of the last in a series of intellectuals who accompanied the national liberation movements, using his abilities to elaborate the theory of the struggle and amplify the voices of the struggle. In his ranks are people such as Claudia Jones (died 1964), DD Kosambi (died 1966), Walter Rodney (student and close friend of Archie’s, assassinated 1980), Ruth First (assassinated 1982), Mahdi Amel (assassinated 1987), Debiprasad Chattopadhyaya (died 1993), and others, but these are the ones that I paid attention to. So many people assassinated, some of them forgotten. Archie, too, has been largely forgotten, his books out of print and his name barely visible on the internet. But this is not about Archie alone. It is about that stance, which believes strongly in the possibility of human freedom and takes refuge in the 1960 UN Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples. That stance–firmly for liberation, eager to accompany the struggle–is slowly making its return.

A few years before his death, I met the Namibian poet Mvula ya Nangolo in Windhoek to talk about art and politics, but more than anything his journalism with Namibia Today. Mvula was interested in my book–The Darker Nations: A People’s History of the Third World (2007)–which tried to recover the story of the struggles of people like him and the intellectual world of people like Archie. Mvula told me what it felt like for Namibians–used to courage of their own and to betrayals of many kinds–to be accompanied by others in their struggle. On the flight from Johannesburg, I had read some of his poems, this one copied into my notebook:

I’ve not been touched so tenderly

I’ve been searched by bullets

going through my camouflage

and leaving my heart so fresh

I wish to feel again how life feels.

That desire to be alive, to push against the reality bequeathed to us.

Editor’s note: Roy Singham, the son of Archie Singham, has donated to non-profit organisations from which New Frame has received funding.