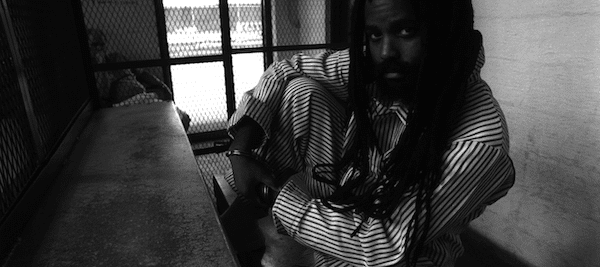

Though he’s spent the last 35 years incarcerated—and at least thirty of those years in isolation on death row, Mumia Abu-Jamal has remained steadfast in his activism, especially in regards to police brutality, criminal punishment, and black liberation.

Abu-Jamal, who was convicted in 1982 of killing Philadelphia police officer Daniel Faulkner, maintains his innocence, and continues to fight for a new trial. In 2011, he had his death sentence overturned on constitutional grounds, and the state of Pennsylvania refused to pursue the death penalty, leaving Abu-Jamal to suffer a life sentence.

While incarcerated, Abu-Jamal has continued to be a target of state persecution. Between 2015 and 2016, he was denied hepatitis C treatment, and in March, after a lengthy battle with the Mahanoy State Correctional Institution in Philadelphia, Abu-Jamal was finally allowed to receive treatment. And yet, these obstacles have not kept Abu-Jamal from writing and further exposing the military industrial project as well as the larger criminal justice system.

In “Have Black Lives Ever Mattered?”, a recently published book by Abu–Jamal, he writes from his prison cell, taking readers on a journey from slavery’s traumatizing past to the brutality of today’s police state.

The collection of essays—the first of which was written in 1998—has the same voice as his previous works, only this time there is an arguably more aggressive call for mobilization.

The essay, “Hate Crimes,” features the story of James Byrd Jr., a black man who was brutally tortured and murdered by two white supremacists in the Texas town of Jasper. He juxtaposed this story with that of another black man in Virginia, who was killed by drinking buddies. This man was beaten, set on fire, and then decapitated.

What’s most striking to Abu-Jamal is how both stories were publicized by the media, and consumed by the public. He writes:

Why is one story a national firestorm, and another a local curiosity? Why is one an unquestioned hate crime, and the other merely a case of ‘boys being boys,’ or a bad mix of liquor and bad company? This is so because the media said it was so, and because the local police told them this.

When is a hate crime a hate crime? When it is a crime of hate, or when the police say it is? And if the cops are to be the arbiters of what is or isn’t a hate crime, who will judge the cops without bias?

Abu-Jamal additionally highlights other violent attacks on black people, including those committed by law enforcement, asking each time, “Was this not a hate crime?”

In “Legalized Police Violence,” written in 1999, Abu-Jamal recounts the story of Tyesha Miller, of Riverside, California, who was killed after police officers rained down a hail of bullets—24 of them—on her vehicle. Twelve of the bullets hit Miller.

The list of victims of police violence and racist brutality is long, and Abu-Jamal burns their names into our heads. His words pierce with as much power and impact as if they had been penned today.

“The suffering of the slain, because they are young and black, are all but forgotten in this unholy algebra that devalues black life while heightening the worth of the assailants because they work for the state,” he writes. That this still applies today, in its entirety, is chilling.

Abu-Jamal’s final passages center around what comes next. While drawing on the civil rights movement, and the black liberation movement, Abu-Jamal discusses present organizing efforts with Black Lives Matter, and the new police state these efforts face.

“Cops, armed with the awesome powers of the state, are now doing what Klansmen did several generations ago—and a new/ancient movement stirs from generations of chronic injustice, passionate indignation, and knowledge of successful insurrectional histories. When the state permits its servants to take the life of living, breathing, growing, wondrous children, it ceases to have a reason to exist in the world. It has failed utterly,” Abu-Jamal argues.

Perhaps, that is the force that fuels today’s youth to fearlessly stand up against automatic weapons, armed Humvees, and sniper rifles, as have the youth of Ferguson. They are fueled by deep and moving forces that compel them to confront the state terror unleashed against them.

This is “their time,” according to Abu-Jamal. In many ways, the elders have failed the youth, he contends, and now it is their turn to take up the fight.

Roqayah Chamseddine is a Lebanese-American writer, published poet, and journalist.