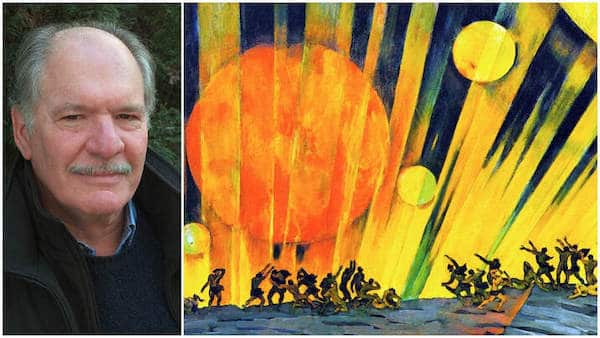

San Francisco State University professor Daniel Langton has called Frederick Pollack’s poems “necessary” because “do what poetry should do—grapple with the important.” He has produced two book-length narrative poems—The Adventure and Happiness, both from Story Line Press—and several published collections of shorter poems, including A Poverty of Words, (Prolific Press, 2015) and Landscape with Mutant (Smokestack Books, UK, 2018).

With decades of poetry behind him and new works still appearing almost constantly, Pollack is one of the country’s most prolific poets. For 20 years, he was also a teacher of creative writing at George Washington University.

In this interview with Pollack, People’s World culture writer Michael Berkowitz asks about socialism, history, the future, and poetry’s role in all of those.

Readers can check out samples of Pollack’s work here, here, here, and here.

Berkowitz: You refer to yourself as a socialist. How are these politics reflected in your work?

Frederick Pollack: I take the “scientific” part of Marx’s “scientific socialism” quite seriously—as long as “science” extends to what German calls “Wissenschaft,” and emphasizes the dialectical method. “Reality divided by reason,” said Hegel, “always leaves a remainder.” For me, to put it crudely, poetry is that remainder.

More precisely: Dialectical reason, in its continual attempt to adequate itself to a changing reality, always leaves some material unaccounted for and generates more. That material includes issues of individual and group psychology, irrational motivation, morality, ethics, and “spirituality”—a word I seldom use but which corresponds to something.

I don’t see these factors as ahistorical, or as having priority over the economic struggles foregrounded by Marxism. Neither, however, do I see them as secondary, mere epiphenomena of those struggles. Poetry, like every art, is a kind of enzyme, breaking down material that is conceptually indigestible.

What led you to this worldview?

I was born in 1946; my parents were in their late 30s. Though both were down-the-line Roosevelt Democrats, they had been quite involved with the art and political struggles of the Depression. In a way, as I grew up, I was too. At Yale, I was a student of Harold Bloom’s and adopted his sacralized view of the creative imagination.

I had, however, a friend, who was both brilliant and already a Marxist. “You must realize,” he once told me, “that, as far as the ruling class is concerned, what you have is a hobby.” Now, nearing the end, I remain stuck with both that insight and my inability to do anything but write.

What poets have especially influenced your work?

Since I started writing, I’ve felt a special rivalry with Yeats. I understand his desire to create a myth to give himself metaphors; what I do almost inverts that. At the core of my myth is not “Byzantium,” but an absence—not so much that of The Revolution as of the comradeship, joy, and engagement it was supposed to bring. I’ve learned from other poets who made their own myths: Gunnar Ekelöf, HD.

At the same time, I love precision, a critical humanism: Zbigniew Herbert, Brecht, Milosz, Oppen and Reznikoff, Roy Fuller. Two Communist poets I admire are Nazim Hikmet, with his genuine love of people (whom he saw through prison bars), and Yannis Ritsos, who accomplished miracles of observation without narrative or abstraction. I share neither of their strengths.

You taught young people for so many years; what advice did you give them?

These were college kids, ranging from freshman to senior. Most of them came from well-off families. Many had suffered the secret horrors of bourgeois life, yet retained a vast naiveté. I explained “ideology” and said the most prevalent ideology is the idea that there’s a thing called “the private life.”

On the board I drew a small circle, orbiting a big circle labeled “History–Society–Nature.” Then I erased both, drew one big circle, and said:

‘There is no such thing as a ‘private life.’ You’re a part of history, and history is in you. Your most shameful secret or fantasy is as much a part of reality as [insert current scandal]. Most poets serve the prevailing ideology. They write poem after poem about their parents or childhoods. Most of these poems are garbage. Don’t write them. Observe the world and how it’s reflected in you. Look at what others do and at what youdo, not just what you feel. Research. Read. Imagine. The phrase ‘Write what you know’ was invented to keep you harmless. In each poem, what real poets ‘know’ is more than what they’ve allowed themselves to know before that point. Don’t preach. Don’t pretend to be wise, to know the answers. In poetry as in science, what matters are not answers but doubts and questions. Don’t try to shock. When you have a good idea, it will shock you.’

That was the best advice I gave.

You come out of a tradition of poetry that struggles toward a better world. Does that tradition still exist?

Bloom was politically ignorant, but he had a great phrase about Shelley; he said he belonged to “the Permanent Left.” Shelley’s my main man. (I can’t meaningfully compare myself to Blake, though I wish I could.)

It’s worth remembering that Shelley, Keats, and Byron were radicals in a period of extreme reaction. Shelley, who died at 30, described himself as “the last fly of a scattered swarm.” But in Prometheus Unbound, which I consider the greatest revolutionary poem, he said that the task of the poet is “to hope till hope creates / From its own wreck the thing it contemplates.”

The “Permanent Left” of poetry is less a tradition than a consuming impulse; the “tradition” may rekindle when one encounters a scrap of paper, or something at the edge of a screen.

Are you optimistic about the future?

No. Nothing commensurate with the danger is being done about global warming. As nearly as I can imagine the minds of the plutocrats, I think what they want is the feeling of absolute advantage—power in the crudest sense, of being at ease while others suffer.

There’s a marvelous poem-sequence by W. D. Snodgrass called In the Fuhrer Bunker; it imagines that Hitler, at the end, felt he was winning. I foresee similar bunkers, amid vaster destruction. The energy of fascism comes from offering the majority the same sadistic delight their exploiters feel; we have not yet effectively confronted those emotions. I’m quite certain, however, that the last battle will be fought in a landscape consisting of desert and swamps, both poisoned.

As for how and why I write, seeing the future thus, I refer to my first remarks. There is a kind of optimism inherent in the work of writing; it’s one of those irrational residues the dialectic builds on.