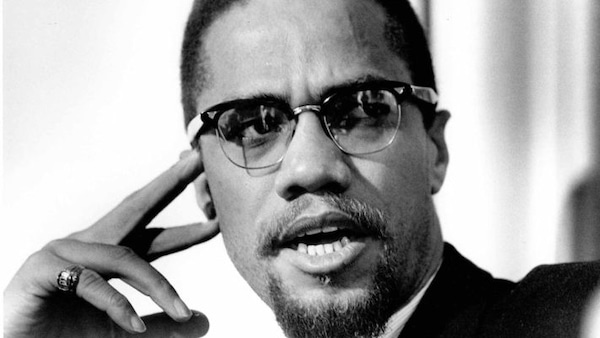

When Malcolm X was assassinated in 1965, the revolutionary flames of Black nationalism he had ignited could not be dimmed. If anything, the name ‘Malcolm X’ is indelibly engraved in the hearts of millions of not only in the United States but in the rest of the world. But here was a man whose life was mostly misconstrued and whose words and actions were wrongly branded as racist “hate speech”.

What he strove for, with his life, was the creation of a revolutionary consciousness for Black people in America to be proud of their identity so as to outmaneuver the white capitalist system subjugating them; a resurgent Black nationalism.

There is a plethora of literature immortalizing Malcolm X’s heroism, whose martyrdom continues to inspire millions across the globe. But indispensable aspects of his revolutionary battle against white supremacy and capitalism are obfuscated by such simplistic mainstream glorification.

Malcolm X’s work after his public dissociation with Elijah Muhamad and departure from the Nation of Islam is a blurry episode in his potent but turbulent activist career. He is often cast as a despicable and “violent” villain who led an irresponsible radical movement of Afro-American emancipation.

The Missing Chapter: Malcolm X and the Organization of Afro-American Unity

His disillusionment with the Nation of Islam (accusing it of “preaching brotherhood but not practicing it”) inspired in him radical self-discovery and knowledge. He realized the Afro-American struggle had to be grounded in its proper international context for solidarity with all Black people in the world.

As such, the movement for Black nationalism he spiritedly built in the last phase of his life–the Organization of Afro-American Unity–is not given the attention it fully deserves. It was a crucial learning curve for him that was cut short, but that still lives forever.

Malcolm X birthed the Organization of Afro-American Unity in the spring of 1964, and did so under extremely hostile conditions. His local and global notoriety for radicalism (which attracted a massive following) put him under perpetual scrutiny. The death of Malcolm X militated the incipient but vibrant hope of an “exceptionally able commander from the battlefield … to train the officers and assemble the troops for an army of Afro-American emancipation”. The radically enlightened teachings of Malcolm X delivered via the Organization of Afro-American Unity must be spread to the world in contemporary times with greater urgency and truth.

With this new movement, Malcolm X sought to remedy the inefficiencies of the Nation of Islam. He envisioned an all-encompassing revolutionary body that was internationalist in outlook. And blind to racial and class barriers. To him it was no longer the “Negro struggle”–but the “Black struggle”.

When he left the Black Muslim movement, he travelled to African and Asian countries including Ghana, Liberia, Kenya, Tanzania, Egypt, Kuwait, Algeria, Lebanon, and Guinea and met revolutionary leaders of the times–Gamal Abdel Nasser, Julius Nyerere, Jomo Kenyatta, Milton Obote, Nnandi Azikiwe, Sekou Toure, and Kwame Nkrumah.

Renewed Revolutionary Ideology and Practice in the Last Months of Malcolm X

Malcolm X asserted that the Afro-American civil rights struggle was not confined to North America. It had to identify with the emerging tide of revolutionary nationalist independence movements on the African continent.

The Negro struggle in America had to share solidarity with revolutionary movements in Latin America, the Caribbean islands, and Asia–“the world is in trouble,” he proclaimed. He dropped the strict stance of racial separateness as the precedent for Black liberation in America because with the Organization of Afro-American Unity, his mobilization encompassed “all humanity”.

In a February 1965 address, he affirmed that for those involved with the Organization, the first step was to “come up with a program that would make our grievances international and make the world see that our problem was no longer a Negro problem or an American problem but a human problem. A problem for humanity.”

A Global “Human Rights” Struggle

Malcolm X elucidated that the “world was in trouble” because of the machinations of white capitalists hell bent on maintaining the illegitimate system of racism and segregation–and how “balances of power” were shifting.

Not all white people were morally catastrophic in attaining global peace–the fight was against white supremacy orchestrated by the racial segregationists namely the ruling elite in Western civilization.

Malcolm X abhorred the term “civil rights” struggle. This limited the Black cause to America. Hence, fewer allies and solidarity. It had to be called the “human rights” struggle–this way, Afro-American nationalism would become international, transcending American borders: a global Black nationalism. With United Nations justification via the UN Charter. More international solidarity, more international allies.

Faced with scant resources and monstrous demonization, Malcolm X was unwaveringly loyal towards the resolute goal of enlightening not only Afro-Americans but the whole world with the objective truth–that the “dark world is rising”. Afro-Americans now had the chance to produce the “fall of the white world” and had to seize it. This was not racist talk, he unflinchingly insisted. His discourse was merely rooted in history. And how Europeans had twisted it.

Given the context of the 1960s where oppressed peoples in Africa, Latin America, and Asia were rising against white supremacist imperialism, Malcolm X brimmed with the global vision of total Black emancipation. And little is said about this chapter in mainstream media.

The Link Between African and Afro-American History to Restore Black Pride

Malcolm X, through the newly born Organization for African Unity, painstakingly, but with a joyous heart, illustrated how the plight of the Black man in America was inseparable from history: Black ancient civilizations, the slave trade, and colonialism.

His biography vindicates him as a committed demagogue and pragmatist who understood that Black people in the Western hemisphere had their history stolen from them via the “Negro” labelling. Blacks in the Western hemisphere had no language, no religion, no customs and beliefs–no identity.

“Now if we don’t go into the past and find out how we got this way, we will think that we were always this way … you once had attained a higher level, had made great achievements, contributions to society, civilization, science and so forth.”

Malcolm X said this in January 1964, arming the nascent movement with a broader international scope so that the Black person on 8th Avenue or Lenox Avenue could realize how events in South Vietnam or the Congo directly affected his living–“his salary, [and] his reception or lack of reception into society”.

Blacks, not Negros, would thus be “immediately interested in things international”. He wanted the Organization of Afro-American Unity to inspire a culture of “broadened reading habits” to widen the scope of Afro-Americans.

He refused to be labelled as a “racist” who fomented “hate speech” and “violence”–this was clearly white supremacist cheap propaganda spewed by the press. The racists in power, he argued, could not carry their egregious atrocities against the “dark world” without the mass consent of the public–the white public.

Advancing counter-narratives on the basis of one’s identity (being Black) should not be called racism or hate speech, he said. Telling Black people to resist unending state violence was not being violent; one cannot sit around and do nothing when faced with untold suffering and injustice.

As such he illustrated how Blacks on the African continent, present-day Middle East and the Indian subcontinent built glorious ancient civilizations. Far ahead than European civilizations. He cited the Egyptians, Sumerians, Dravidians, Carthage (led by Hannibal, who was Black, though “made white by Hollywood”), and the Ethiopians. Including the West African cultures in Ghana (a territory stretching farther than present-day Ghana), Mali, and the Moors. Malcolm X refused to celebrate Negro History Week because it had no true origin as it made the world think that Black history starts in the slave plantations.

The Afro-American had to identify and with this rich history of Black ancient civilizations and own it. Furthermore, they were supposed to identify with liberation movements rising in Africa, Latin America, and Asia.

The trips that Malcolm X undertook in Africa and Asia were critical in shaping this refined discourse that he led via the Organization of Afro-American Unity–which is the missing chapter in the life of Malcolm X as presented in mainstream media and literature.

For Malcolm X, this was the only way to extricate the Black race from the throes of white capitalist hegemony causing war and strife on earth. In all this, he never lost his Muslim identity. He simply gave it more scope, and objectivity for the emancipation of everyone.

The Missing Chapter Resurrected

The crystal-clear history that Malcolm X delivered in his last days of his life under the Organization of Afro-American Unity provided powerful seeds for a strong black nationalism. With Black pride restored, Afro-Americans would happily identify with the African continent providing tremendous Black unity that would overthrow the violent capitalist system oppressing the Black race.

This would create an unbreakable link between Black nationalism and revolutionary socialism, given that Malcolm X was not avowedly Marxist yet. His assassination killed the “latent socialism” he was stirring via Black nationalist struggles.

This matters because the liberation movements across the world that he praised were rooted in socialist principles. The seeds he left created vital patterns of solidarity between black nationalism originating in Afro-American struggles for human rights and socialism across the world.

Nevertheless, the work he carried through the Organization of Afro-American Unity–under great difficulties–must be propagated with renewed vigor. Malcolm X’s missing chapter is definitely the Organization of Afro-American Unity because it ultimately led to his assassination.

For decades his assassination was shrouded in mystery until a recent deathbed confession by Ray Woods (an undercover police officer then) claiming responsibility for Malcolm X’s death by ensuring the arrest of his security detail days before he was shot at the Audubon Hall in New York. This was done so that Malcolm X would be unguarded on the assassination day. The missing chapter in Malcolm X’s biography must be fervently resurrected.