May Day is known throughout the world as International Workers’ Day. It is celebrated in over one hundred countries to highlight workers’ struggles and triumphs. Though the movement celebrating May Day originated in the United States, it is not a recognized holiday there. May Day commemorates the mass protests on May 1, 1886, for the eight-hour day, when sixty thousand workers went on strike in Chicago, and the subsequent Haymarket Affair, where eight labor organizers were hanged by the state. This was a pivotal event in the history of workers’ and anarchist movements.

In Scotland, for example, a number of trades councils hold events on or around May 1. The festival in Glasgow has always been well attended and has a long tradition going back to the days when heavy industry provided much of the job for working class people in the city: dangerous, hard labor that was low paid and extremely exploitative conditions. May Day was a day to dress up smart, spend time with family, friends, and fellow workers, highlight problems in the workplace, and be inspired and emboldened by trade union representatives and guest speakers from around the world. Educate, agitate, organize, and have fun!

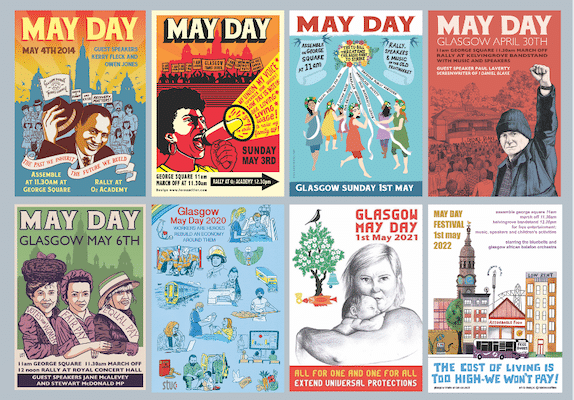

In 2014, I was asked to design the Glasgow May Day poster and I have been doing it almost every year since. Every year there is a new theme linked to local and international, past and present, trade union activism. My body of work is, in a sense, a historical record in itself. The very first poster I designed was based on an old, silent film about U.S. bass-baritone concert artist, stage and film actor, athlete and activist Paul Robeson, who led the May Day march in 1960. I was touched by how he kept doffing his cap to the huge crowd cheering him on, an enthusiastic welcome from ten thousand people. “There can be no question that we, the people, in the deepest sense, create the wealth,” he told the audience. “We are building a world in which we can live a rich and decent life, and we and our children should enjoy it.” He sang old favorites Water Boy and Old Man River as well as a song of peace. The following day, he led a miners’ gala day parade in Edinburgh. I was asked to create an image that linked this wonderful moment in history with that year’s theme: the impact of austerity policies on the majority of residents. Columnist and author Owen Jones was the keynote speaker, known for speaking out for those most disadvantaged by the Westminster government and their friends in the media, and for his acclaimed nonfiction work Chavs: The Demonization of the Working Class. I enjoyed walking at the head of the march with Owen and Kerry Fleck, a trade unionist from Belfast. We chatted and laughed about all sorts, including Owen’s beloved pet cats and the funny things they do.

In 2014, I was asked to design the Glasgow May Day poster and I have been doing it almost every year since. Every year there is a new theme linked to local and international, past and present, trade union activism. My body of work is, in a sense, a historical record in itself. The very first poster I designed was based on an old, silent film about U.S. bass-baritone concert artist, stage and film actor, athlete and activist Paul Robeson, who led the May Day march in 1960. I was touched by how he kept doffing his cap to the huge crowd cheering him on, an enthusiastic welcome from ten thousand people. “There can be no question that we, the people, in the deepest sense, create the wealth,” he told the audience. “We are building a world in which we can live a rich and decent life, and we and our children should enjoy it.” He sang old favorites Water Boy and Old Man River as well as a song of peace. The following day, he led a miners’ gala day parade in Edinburgh. I was asked to create an image that linked this wonderful moment in history with that year’s theme: the impact of austerity policies on the majority of residents. Columnist and author Owen Jones was the keynote speaker, known for speaking out for those most disadvantaged by the Westminster government and their friends in the media, and for his acclaimed nonfiction work Chavs: The Demonization of the Working Class. I enjoyed walking at the head of the march with Owen and Kerry Fleck, a trade unionist from Belfast. We chatted and laughed about all sorts, including Owen’s beloved pet cats and the funny things they do.

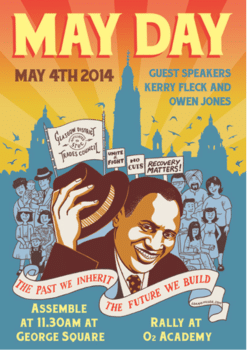

The 2015 poster also linked past and present international protest. “We Are Not Rats” as a slogan came out of the iconic speech by Glaswegian Jimmy Reid: “The rat race is for rats. We are not rats.” His speech was reprinted in full by the New York Times and projected the Clydeside shop steward to a new level of popularity. He was voicing the feelings of many who felt chained to their lives within monopoly capitalism. The theme for the 2015 May Day Festival was young people who face the brunt of this unjust capitalist system of austerity, enduring insecure low-paid employment and zero-hour contracts. The placards in the background were inspired by the Memphis sanitation workers’ strike in 1968 during the civil rights movement.

The 2015 poster also linked past and present international protest. “We Are Not Rats” as a slogan came out of the iconic speech by Glaswegian Jimmy Reid: “The rat race is for rats. We are not rats.” His speech was reprinted in full by the New York Times and projected the Clydeside shop steward to a new level of popularity. He was voicing the feelings of many who felt chained to their lives within monopoly capitalism. The theme for the 2015 May Day Festival was young people who face the brunt of this unjust capitalist system of austerity, enduring insecure low-paid employment and zero-hour contracts. The placards in the background were inspired by the Memphis sanitation workers’ strike in 1968 during the civil rights movement.

The “I Am a Man” slogans displayed en masse above the heads of the twenty-five thousand civil rights activists is a powerful, lasting image that appeals to the heart in a direct way. It represents peaceful dignity and self-worth in the face of discrimination and violent state attack. Historically, the term boy was used as a demeaning, racist insult toward men of color, Black men in particular. In response, “Am I not a man and a brother?” became a catchphrase used by British and U.S. abolitionists. The “I am a man” slogan developed out of this.

The Memphis sanitation workers’ strike was a strong movement in which local high school and college students participated, nearly a quarter of them white, alongside sanitation workers in daily marches supported by Martin Luther King Jr. and other national civil rights leaders. King praised the group’s unity: “You are demonstrating that we can stick together. You are demonstrating that we are all tied in a single garment of destiny, and that if one black person suffers, if one black person is down, we are all down.” King was brutally assassinated during his visit to Memphis for the strike.

The 2015 May Day Festival also centered the U.S. fast-food worker movement, in which workers campaigned to raise wages and gain rights at work including union representation. The main character in the poster and the slogans depicted emanating from the megaphone represent this movement. The fight for $15 minimum wage (and a union) continued and acted as a springboard for other movements, including Black Lives Matter. Since the first Fight for $15 strike in 2011, workers have won wage increases for 22 million in the United States, including tens of thousands in New York State.

The 2015 May Day Festival also centered the U.S. fast-food worker movement, in which workers campaigned to raise wages and gain rights at work including union representation. The main character in the poster and the slogans depicted emanating from the megaphone represent this movement. The fight for $15 minimum wage (and a union) continued and acted as a springboard for other movements, including Black Lives Matter. Since the first Fight for $15 strike in 2011, workers have won wage increases for 22 million in the United States, including tens of thousands in New York State.

In 2016, I designed the poster around my version of the May Day maypole, a tradition associated with European folk festivals. May Day is also the ancient celebration of spring and rebirth—the traditional time for planting new seeds in old ground. I wanted to bring a spirit of joy and optimism at a time when the introduction of the Trade Union Bill represented the biggest assault on working people’s rights in living memory. It was a deliberate attack on public sector trade unions and shifted the balance of power in workplaces toward the advantage of employers and away from workers. In spite of this, a united movement was created, resulting in heavy blows to the Conservative government’s plans. At the top of the maypole there is a garland of flowers decorating the assertion that “the TU Bill threatens the basic right to strike.” The white ribbons hanging down depict various slogans that represent some of the triumphs of worker organizing, such as “equal rights for all,” “a living wage,” “paid holidays,” “workplace pensions,” “paid maternity leave,” “workplace safety,” and “defends public services.”

I also wanted to pay tribute to some of the young women activists who were involved in various political campaigns at the time, so I depicted them wearing bright colors and flower crowns, holding ribbons and dancing. Better than Zero, for example, was a movement spearheaded by young people, formed by precarious workers in 2015. In 2016, one hundred thousand workers were on zero-hour contracts in Scotland. That same year, Better than Zero took on the GI group, a £45 million empire of restaurants, pubs, and nightclubs that failed to pay minimum wage to thousands of its zero-hours workers. Workers took them to tribunal and won.

I also wanted to pay tribute to some of the young women activists who were involved in various political campaigns at the time, so I depicted them wearing bright colors and flower crowns, holding ribbons and dancing. Better than Zero, for example, was a movement spearheaded by young people, formed by precarious workers in 2015. In 2016, one hundred thousand workers were on zero-hour contracts in Scotland. That same year, Better than Zero took on the GI group, a £45 million empire of restaurants, pubs, and nightclubs that failed to pay minimum wage to thousands of its zero-hours workers. Workers took them to tribunal and won.

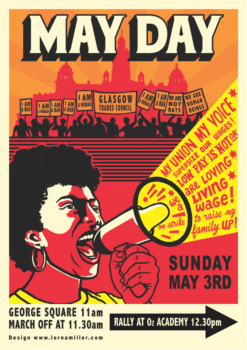

The theme of the 2017 poster was the heartbreaking Ken Loach film, I Daniel Blake; the screenwriter Paul Laverty was the May Day festival guest speaker that year. The film won the Palme d’Or at Cannes in 2016 and is described as one of Loach’s finest films. This is my favorite poster, not least because I have a photo of Ken proudly holding it. The film starsDave Johns as Daniel Blake, a middle-aged man who is refused employment and support allowance because he cannot walk fifty meters and “raise either arm as if to put something in your top pocket,” even though his doctor instructed him to rest after having suffered a heart attack at work. He befriends a young single mother who is facing her own struggles within a cruel, humiliating system that pushes anyone needing support to breaking point. She is sanctioned for arriving late to her job centee appointment. They are pulled together amid horrifying circumstances out of their control. With biting humor and the will to survive and thrive, they struggle on. “My name is Daniel Blake. I am a man, not a dog. As such, I demand my rights. I demand you treat me with respect. I, Daniel Blake, am a citizen, nothing more and nothing less. Thank you.”

We had to ask permission to use the iconic image of Daniel with his fist defiantly raised, which was well known from the film’s promotional material. I drew a graphite pencil version of it. In the background, I drew Kelvingrove bandstand as it would look on the day of the festival, filled with people. It was a triumphant victory of community activism that the bandstand could be used at all. The determined people of Glasgow had brought it back to its former glory after many years of committed campaign work. The iconic clamshell amphitheater surrounding the cast iron bandstand, constructed by architect James Miller, was opened in 1924. Situated in Kelvingrove Park, with a dense foliage backdrop of glorious mature trees, Scotland’s first open air concert venue had fallen into a sorry state of disrepair and dilapidation by the 1990s. Devoted locals saved the much-loved bandstand from demolition and proceeded to fight for proposed restoration works, setting up the campaign group Friends of Kelvingrove Park. Thanks to their successful fundraising efforts and many community-organized family fun days, in 2000 the bandstand received listed building status by Historic Scotland and the restoration process could begin. It opened in May 2014 to everyone’s delight.

My 2018 poster brings together Glaswegian women activists from different decades that fought for equality through the trade union movement. Mary Macarthur (1880–1921), on the left, was a suffragette who rebelled against her Tory family to become chair of the Ayr branch of the Shop Assistants’ Union, then became secretary of the Women’s Trade Union League when she moved to London in 1903. In 1906, she formed the all-female National Federation of Women Workers to support women who worked in some of the worst paid jobs in the country. She gave them a voice to make sure that their wages were higher and conditions were better. She led women in the chain-makers strike of Cradley Heath in 1910 in their fight for better pay, saying: “Women are unorganised because they are badly paid, and poorly paid because they are unorganised.” The ten-week strike ended in victory with the employers agreeing to pay the minimum wage. Macarthur’s life was cut short at the age of 40 due to cancer, but she achieved more than most people would in twice that time.

My 2018 poster brings together Glaswegian women activists from different decades that fought for equality through the trade union movement. Mary Macarthur (1880–1921), on the left, was a suffragette who rebelled against her Tory family to become chair of the Ayr branch of the Shop Assistants’ Union, then became secretary of the Women’s Trade Union League when she moved to London in 1903. In 1906, she formed the all-female National Federation of Women Workers to support women who worked in some of the worst paid jobs in the country. She gave them a voice to make sure that their wages were higher and conditions were better. She led women in the chain-makers strike of Cradley Heath in 1910 in their fight for better pay, saying: “Women are unorganised because they are badly paid, and poorly paid because they are unorganised.” The ten-week strike ended in victory with the employers agreeing to pay the minimum wage. Macarthur’s life was cut short at the age of 40 due to cancer, but she achieved more than most people would in twice that time.

To the right of Macarthur is Agnes McLean (1918–94), a trade union activist for workers’ rights and a councilor from Glasgow. Born in Ibrox, she came from a family of committed socialists and attended Socialist Sunday School as a child. She began working as a bookbinder at Collins publishing house at the age of 14 and became a Union activist from the start. She successfully argued for the bookbinders to receive a pay raise. “It’s a case of fat profits and wage packets suffering from malnutrition,” she said. During the Second World War, she worked for Rolls-Royce on the shop floor, in engineering component manufacturing with ten thousand other women. She led them on a successful strike for equal pay in 1943, supported by male workers. In the 1960s, she was awarded the Gold Badge of the Trades Union Congress.

Next to McLean is Denise Phillips, a UNISON (Scotland’s biggest public service trade union) activist and homecarer. Phillips marched with hundreds of women from Glasgow Green to George Square, dressed as Suffragettes as part of UNISON’s equal pay campaign in 2018. She is wearing a bonnet decorated with the distinctive purple, white, and green Suffragette colors that I used as the main color scheme for the poster. Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, coeditor of Votes for Women magazine, devised the concept of the Suffragette colors in the 1900s. Purple stood for loyalty and dignity, white for purity, and green for hope. The twelve-year dispute over equal pay for care, catering, cleaning, caretaking, administrative, and educational support roles for Glasgow City Council (mainly by women) was said to be the biggest strike by workers over equal pay since the 1960s, and the biggest-ever equal pay strike in the United Kingdom. An agreement was reached in 2019, with organizer Rhea Wolfson stating: “The strike succeeded in its aim of making the council take these claims seriously. It was also a spectacular event that put equal pay for low-paid women on the national agenda.”

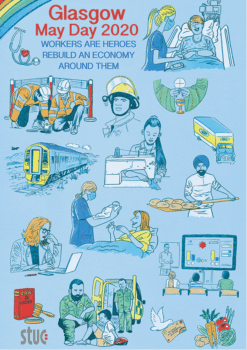

I started working on my next poster during the 2020 lockdown, when a new and deadly virus paralyzed the whole world. Everyone had to suddenly adjust and I was feeling terribly ill. There was no community testing available at the time, but it was clear that I had caught COVID-19. My general practitioner told me to visit one of the treatment centers that had been set up, but then changed her mind. Apparently, since my lips weren’t turning blue and I could breathe, I was on my own, a single mother, living with the worst fear that my son would find me dead. I had never experienced an illness like this before. I carried on as best as I could with waves of nausea, dizziness, and other distressing symptoms, forcing myself to my desk, glad to have some artwork on which to focus. I had no idea that it was the beginning of two years of chronic illness and fighting for treatment and support with thousands of others, many of whom I was celebrating in the poster. Many frontline workers, who were literally applauded as heroes, were then left on their own to survive long COVID, loss of work, financial difficulty, medical gaslighting, mental health strain, family problems, and more. People reached out to each other online, setting up support groups that also became campaign groups. Trade union activism continued to be a force against state dereliction and inefficiency. Sadly, the poster wasn’t printed and the May Day Festival took place online.

I started working on my next poster during the 2020 lockdown, when a new and deadly virus paralyzed the whole world. Everyone had to suddenly adjust and I was feeling terribly ill. There was no community testing available at the time, but it was clear that I had caught COVID-19. My general practitioner told me to visit one of the treatment centers that had been set up, but then changed her mind. Apparently, since my lips weren’t turning blue and I could breathe, I was on my own, a single mother, living with the worst fear that my son would find me dead. I had never experienced an illness like this before. I carried on as best as I could with waves of nausea, dizziness, and other distressing symptoms, forcing myself to my desk, glad to have some artwork on which to focus. I had no idea that it was the beginning of two years of chronic illness and fighting for treatment and support with thousands of others, many of whom I was celebrating in the poster. Many frontline workers, who were literally applauded as heroes, were then left on their own to survive long COVID, loss of work, financial difficulty, medical gaslighting, mental health strain, family problems, and more. People reached out to each other online, setting up support groups that also became campaign groups. Trade union activism continued to be a force against state dereliction and inefficiency. Sadly, the poster wasn’t printed and the May Day Festival took place online.

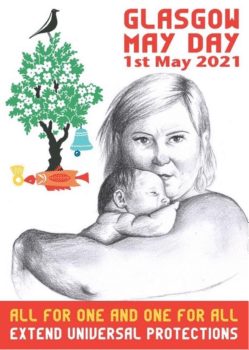

By 2021, we were still trying to assimilate the fact that pandemic restrictions were an ongoing necessity of our lives. We had all been living with unprecedented fear, control, and uncertainty, trying to process grief and loss on a devastating scale. Jokes about the perils of working from home and Zoom meetings were wearing thin and joyful clapping for heroes was replaced by weary despair: everyone was just hoping that the never-ending nightmare would, well, end. The image of a mother and her child was chosen for the year’s poster to represent the resilience to carry on, the new life symbolizing hope for better days. The image is based on a photograph of Debbie and her newborn baby, from Anderston, Glasgow, by documentary photographer Kirsty Mackay: “In Glasgow, as everywhere else a person’s place of birth has a huge bearing on their overall life chances. That first journey home from the hospital, depending on which area home is, will have an impact on health, well-being and life expectancy.” Mackay’s project examining the “Glasgow Effect,” where life expectancy is shorter than the UK average, is available as a book, The Fish That Never Swam. I used charcoal for the drawing, creating a softness that worked well with the serious, determined expression of the mother. The theme of this year’s May Day was the extension of universal protections: specifically free school meals and promotion of the campaign for free public transport. Universal protection of the National Health Service was recognized as fundamental for recovery and, by extending these protections, some of the inequalities and poverty in Glasgow could be tackled. The main speaker at the festival was Christina McAnea from UNISON, who had just been elected as UNISON’s general secretary. I designed a new, stylized version of the well-known bird, fish, bell, and tree that are a part of the Glasgow coat of arms, representing the four miracles that the city’s patron saint, Saint Mungo, is said to have performed during his life.

By 2021, we were still trying to assimilate the fact that pandemic restrictions were an ongoing necessity of our lives. We had all been living with unprecedented fear, control, and uncertainty, trying to process grief and loss on a devastating scale. Jokes about the perils of working from home and Zoom meetings were wearing thin and joyful clapping for heroes was replaced by weary despair: everyone was just hoping that the never-ending nightmare would, well, end. The image of a mother and her child was chosen for the year’s poster to represent the resilience to carry on, the new life symbolizing hope for better days. The image is based on a photograph of Debbie and her newborn baby, from Anderston, Glasgow, by documentary photographer Kirsty Mackay: “In Glasgow, as everywhere else a person’s place of birth has a huge bearing on their overall life chances. That first journey home from the hospital, depending on which area home is, will have an impact on health, well-being and life expectancy.” Mackay’s project examining the “Glasgow Effect,” where life expectancy is shorter than the UK average, is available as a book, The Fish That Never Swam. I used charcoal for the drawing, creating a softness that worked well with the serious, determined expression of the mother. The theme of this year’s May Day was the extension of universal protections: specifically free school meals and promotion of the campaign for free public transport. Universal protection of the National Health Service was recognized as fundamental for recovery and, by extending these protections, some of the inequalities and poverty in Glasgow could be tackled. The main speaker at the festival was Christina McAnea from UNISON, who had just been elected as UNISON’s general secretary. I designed a new, stylized version of the well-known bird, fish, bell, and tree that are a part of the Glasgow coat of arms, representing the four miracles that the city’s patron saint, Saint Mungo, is said to have performed during his life.

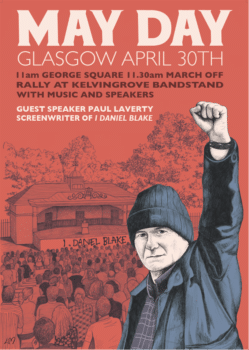

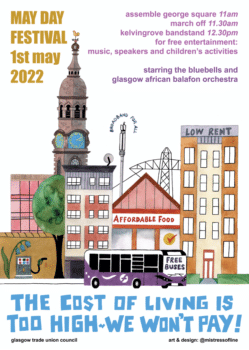

I have just completed the 2022 May Day Festival poster. The theme this year is the cost-of-living crisis. This is another cruel blow for exhausted residents, many of whom have had to deal with reduced income or loss of work due to the pandemic. I created a scene representative of Glasgow, with apartment buildings, one with the slogan “Low Rent,” an electricity pylon, the distinctive St. Andrews in the square tower, a petrol pump, a shop with the slogan “Affordable Food,” a broadband mast with the slogan “Broadband for All,” and a bus that says “Free Buses” on the front. Free public transport was provided for the UN Climate Change Conference delegates and attendees in Glasgow in November 2021, which led people to call for permanent free travel for all on the public transport network. Susan Aitken, leader of the Glasgow City Council, was hoping to trial such a scheme, but the transport minister (who has since stood down for health reasons) said this would not be possible: money was needed to keep public transport running, coping with reduced passenger numbers and staff shortages during the pandemic. Nevertheless, a motion passed by the council recognized work of campaign groups Get Glasgow Moving and Free Our City, who back free public transport and led to Aitken requesting the trial run. In November 2021, first minister Nicola Sturgeon confirmed the introduction of free bus travel for anyone under the age of 22 in Scotland, making around 930,000 people eligible for the scheme. Earlier in the year, legislation was laid in parliament to allow those under 19 to travel free across the country.

I have just completed the 2022 May Day Festival poster. The theme this year is the cost-of-living crisis. This is another cruel blow for exhausted residents, many of whom have had to deal with reduced income or loss of work due to the pandemic. I created a scene representative of Glasgow, with apartment buildings, one with the slogan “Low Rent,” an electricity pylon, the distinctive St. Andrews in the square tower, a petrol pump, a shop with the slogan “Affordable Food,” a broadband mast with the slogan “Broadband for All,” and a bus that says “Free Buses” on the front. Free public transport was provided for the UN Climate Change Conference delegates and attendees in Glasgow in November 2021, which led people to call for permanent free travel for all on the public transport network. Susan Aitken, leader of the Glasgow City Council, was hoping to trial such a scheme, but the transport minister (who has since stood down for health reasons) said this would not be possible: money was needed to keep public transport running, coping with reduced passenger numbers and staff shortages during the pandemic. Nevertheless, a motion passed by the council recognized work of campaign groups Get Glasgow Moving and Free Our City, who back free public transport and led to Aitken requesting the trial run. In November 2021, first minister Nicola Sturgeon confirmed the introduction of free bus travel for anyone under the age of 22 in Scotland, making around 930,000 people eligible for the scheme. Earlier in the year, legislation was laid in parliament to allow those under 19 to travel free across the country.

Designing the posters has always been a wholly collaborative process with Glasgow Trades Council, with special thanks to chair Jennifer McCarey. It is always an ongoing learning process. The approach I take to the work is different from my other main form of creativity of the past ten years: editorial cartooning. It has been an opportunity to experiment with materials and style, and for an artist this is always beneficial for growth. Earlier in my career, I created comic art for children’s magazines, was a digital colorist, and wrote, drew, and designed my own comics. It was good practice for learning a variety of skills (most self-taught) that has enabled me to create the poster designs. I designed my first magazine cover for Scottish arts magazine Variant in 1999. The work of an artist, even a commercial one, is often shrouded in mystery.