President Biden’s 2022 State of the Union Address included a call for a $15 federal minimum wage. According to an Economic Policy Institute study, a phased increase to a $15 federal minimum wage by 2025 would raise the earnings of 32 million workers—21 percent of the workforce, no small thing.

The current federal minimum wage is $7.25. The federal minimum wage was established in 1938, as part of the Fair Labor Standards Act. Congress has voted to raise it 9 times since then, the last time in 2007. That last vote included a mandated three step increase that brought it to its current level in July 2009.

It has been 13 years since the last increase in the federal minimum wage, the longest period since its establishment without an increase. Taking inflation into account, workers paid the federal minimum wage in 2021 earned 21 percent less than what their counterparts earned in 2009, and prices keep rising. Outrageously, this eroding federal minimum wage continues to set the wage floor in 20 states. Where is the justice in that?

Lawmakers have resisted boosting the federal minimum wage for years, no doubt responding to corporate pressure. And, without a strong outcry, Biden’s call for a $15 federal minimum wage will also likely be ignored; in fact, it remains to be seen how hard he will fight for it. We need to shine a bright spotlight on the importance of this demand and do our best to mobilize and apply our own pressure for a long overdue and meaningful increase in the federal minimum wage.

A $15 federal minimum wage is popular

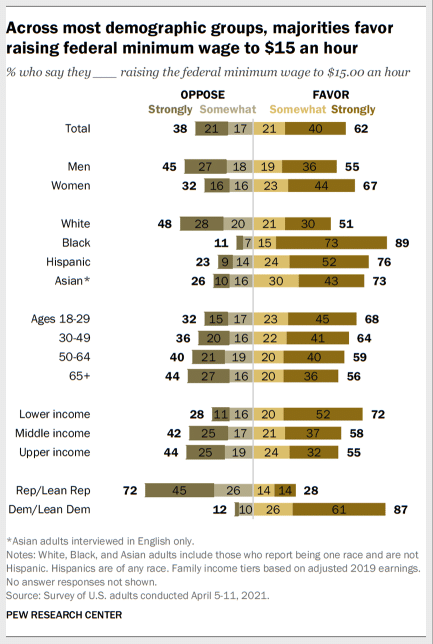

A strong majority of adults support a $15 federal minimum wage. A 2021 Pew Research Center survey found that 62 percent of U.S. adults “favor raising the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour, including 40 percent who strongly back the idea.” Of the 38 percent who oppose a $15 wage, 71 percent said the minimum wage should be higher than it is now. Only 10 percent of U.S. adults said that “the federal minimum wage should remain at the current level of $7.25 an hour.”

Not surprisingly, as we see in the figure below, the younger, the poorer, the stronger support for $15. Black, Hispanic, and Asian adults were also far more favorable to a $15 federal minimum wage than were White adults.

A number of states, as well as some cities, do have minimum wages higher than the federal minimum wage, but the great majority are significantly below $15 an hour. According to the Pew survey, in areas where the minimum wage is set by the federal minimum of $7.25, 59 percent of adults support raising the federal minimum wage to $15. The level of support is the same in areas where the minimum wage is between $7.25 and $11.99 an hour. And in areas where the minimum wage is $12 or higher, 69 percent of respondents voiced support for a $15 federal minimum wage. In sum, there is widespread support for a $15 federal minimal wage.

Why corporations might object to a $15 federal minimum wage

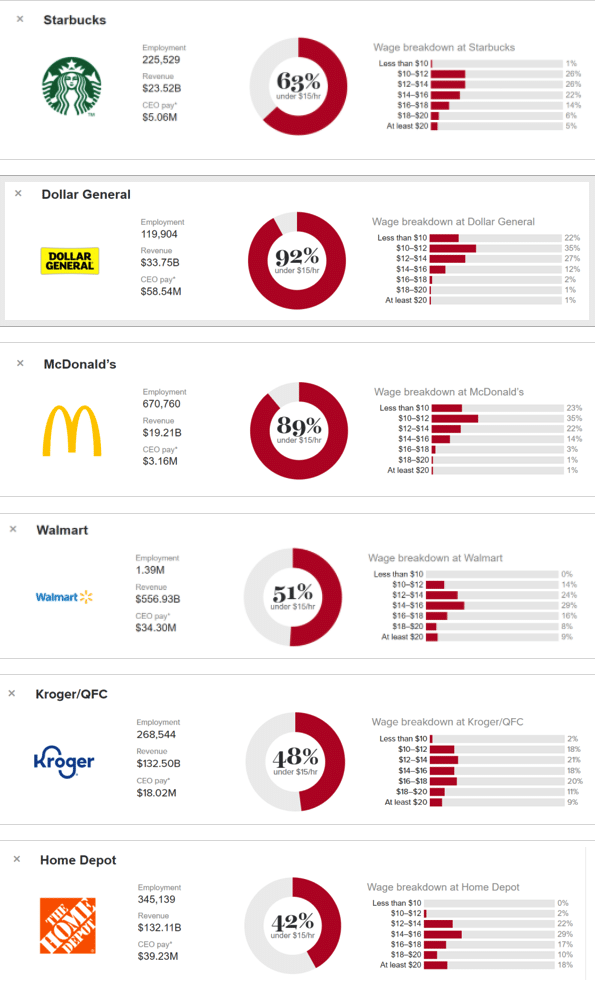

The Economic Policy Institute and the Shift Project have collaborated to produce an on-line interactive company wage tracker. It offers a range of data on 66 large retail and food service firms, including the number of workers they employ, the revenue generated by their U.S. operations, how much they pay their CEOs, and what shares of their U.S. hourly workers fall within certain wage bands. The tracker makes clear that a $15 federal minimum wage would lead to meaningful wage increases for a large share of their employees.

As an Economic Policy Institute post discussing the data notes:

At Starbucks—where workers have sparked a union organizing wave in recent months—63 percent of workers make below $15 an hour. At Dollar General and McDonald’s, 92 percent and 89 percent of workers, respectively, make below $15 an hour, with nearly one-in-four workers making below $10 an hour at both companies. A majority (51 percent) of workers make below $15 an hour at Walmart.

What follows are a few company snapshots that highlight their wage distributions. A look at CEO compensation provides a telling counterpoint.

What follows are a few company snapshots that highlight their wage distributions. A look at CEO compensation provides a telling counterpoint.

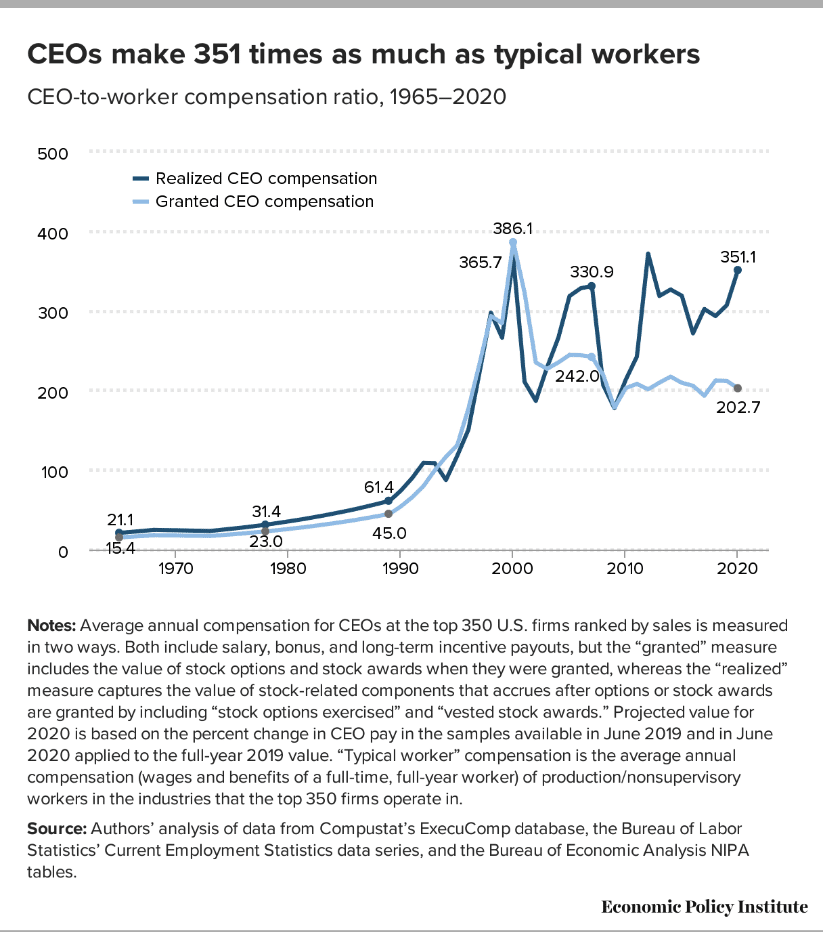

And as intended, reliance on low-paid workers has helped finance a massive transfer to stockholders and an explosive growth in CEO compensation. The latter is illustrated in the following figure.

Minimum wage trends and consequences

In 1968 the federal minimum wage was set at $1.60 an hour. This marks its high point in inflation-adjusted dollars. Taking inflation into account, that wage is equivalent to $11.12 today. Thus, the federal minimum wage, at its current value of $7.25, has declined in purchasing power by 34 percent relative to that 1968 peak. In other words, we need a substantial increase in the federal minimum wage just to restore its past real value.

Of course, as noted above, a number of states have raised their own minimum wages above the federal level—30 states to this point, but only California currently has a $15 minimum wage. Although eleven states will soon join it, having passed legislation or ballot measures that will gradually increase their respective minimums to $15 an hour, the great majority of states have far lower minimum wages. In fact, 20 states still use the existing federal minimum wage.

Opponents of a higher minimum wage claim that a higher wage would prove disastrous for low wage workers as well as the economy. However, a number of careful studies have shown that raising the minimum wage does help its intended beneficiaries. Arindrajit Dube, a highly respected labor economist, summarizes the results of his own work on the effects of a minimum wage increase as follows:

Through my research, I’ve found raising the minimum wage by 10 percent may reduce poverty by 2 to 5 percent, which is a sizeable change. I also find that increases in the minimum wage end up saving taxpayers 35 cents on the dollar from reductions in public assistance.

On the question of intragenerational mobility—wage and earnings growth across a worker’s lifetime—there is strong evidence that higher minimum wages lead to greater wage growth. . . .

In 2019, my colleagues and I published a paper in the Quarterly Journal of Economics that tried to provide a more comprehensive assessment of the effects of minimum wages on low-wage jobs. We looked at effects on low-wage jobs that pay slightly at or above the minimum wage and at jobs across the distribution.

When looking at minimum wage increases up to 2016, we found these increases didn’t seem to have much of an impact on jobs. We then looked at what happens when the minimum wage is 50 to 60 percent of the median wage and didn’t see evidence of job losses at those levels. That was an encouraging finding. In 2014, as I wrote my Hamilton Project policy memo, I thought maybe 55 percent of the median wage was a safe place to land for many places. But in the past five years, we have expanded the evidence base substantially, and the evidence has continued to be positive.

In a recent paper, we looked at 21 large cities that raised minimum wages. Some had raised them as much as 80 percent of median wages. And yet, looking over a long period of time, we didn’t see evidence of a reduction in low-wage jobs compared with other cities.

As noted above, the Economic Policy Institute actually did a study of the consequences of phasing in a federal minimum wage of $15 by 2025. It concluded that it would raise the earnings of 32 million workers. More specifically, it would:

- Raise the wages of at least 19 million essential and front-line workers—60 percent of all workers who would see a pay increase.

- Increase pay for nearly one in three Black workers (31 percent) and for one in four Hispanic workers (26 percent), compared with about one in five white workers.

- Lift out of poverty up to 3.7 million people—including an estimated 1.3 million children.

- Result in an annual pay increase of about $3,300 for affected workers working year-round. In total, a rising wage floor would provide over $108 billion in additional wages to affected workers.

The focus here is on the benefits of a $15 federal minimum wage, but there is nothing magical about this number, and it is far from ensuring a living wage in most of the country. In fact, the economist Dean Baker has pointed out that one could easily make the case that the minimum wage should be tied to the growth in productivity. As he notes,

We actually did have a minimum wage that kept pace with productivity growth from when it was created [in 1938] until 1968, so for three decades. And of course, the economy did very well in that period.

According to calculations done by the Center for Economic and Policy Research, if the federal minimum wage had continued to grow at the same pace as productivity, our current productivity and inflation adjusted federal minimum wage would be $23 an hour. From that perspective, a $15 federal minimum wage represents a modest boost.

Increasing the federal minimum wage to $15 certainly won’t solve all our problems, but as the studies cited above make clear, such an increase is both doable and would be a game changer for many working people and their families. Moreover, a spirited campaign in support of the increase could help focus attention on both the importance of public policy for achieving desired social outcomes and the ever more punitive nature of our current economic system.