As a young adult who ‘got into’ politics at a very young age, I remember being talked at and not talked to when it came to politics. Politics was ‘grown folk’s business’. I’d be told I did not have the credentials, the books under my belt, the academic language to voice my opinions, the facts, the figures, to ‘know’ about politics. I quickly realised that many adults did not have that expertise either but having lived longer, they had experienced politics enough to discuss it with authority. For many young people, an encounter like this is enough to turn them away from wanting to understand and partake in the matters that affect them, whether they are conscious of its far-reaching impacts or not.

As a 16-year-old, you could finish secondary school without a shred of knowledge about the inner workings of the country you live in. This is because the syllabuses and modules taught often do not cover the political system. The selective nature of the content that is taught, further demonstrated by the government’s concerted efforts to shut down important discussions on anti-capitalism, for example, leaves students with no basic understanding of their structural reality.

At A-Level, the story is the same. Unless you study certain humanities subjects, or have an extracurricular interest in politics, you may leave school at 18 and enter the workforce or higher education without any knowledge of your rights and civil liberties. Many young people who do not have an interest in politics, politically literate parents, or teachers who share this knowledge, find politics completely inaccessible. It’s not hard to understand why.

The Political Education Project

I am one of the lucky ones. My parents taught my sister and I from a young age that politics is important. They created an open learning environment where they engaged with our questions and introduced books for us to discuss at length. They took us to protests and grassroots events and brought us into a community of adults who did not gate-keep political intellect for self-aggrandisement. Seeing how much this was the exception and not the norm, I jumped at the opportunity to be a young contributor to the socialist community-run programme aptly named the Political Education Project (PEP). It offered anyone and everyone what my parents had exposed me to.

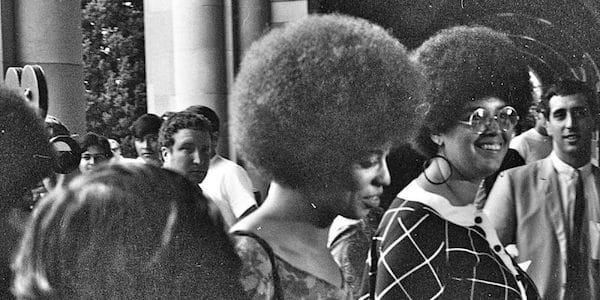

The project was set up by trade unionists, activists, lecturers, and grassroots organisers who wanted to ‘initiate a new effort in working class self-education in Britain, Ireland and the US–drawing on the traditions of working-class pedagogy from trade unions, the civil rights movement and community organising’. Its programme covered a wide range of topics, including socialism, women’s oppression, anti-racism, the Covid-19 pandemic, climate and capitalist crises, and building working class power. Those attending were exposed to diverse left-wing political analysis within texts, including A Sivanandan’s Communities of Resistance: Writings on Black Struggles for Socialism and Hal Draper’s The Two Souls of Socialism, which contributors selected based on their connection to the community efforts they were engaged in.

This work has been particularly important given that over the past 50 years, there has been an active effort to weaken community infrastructures that upheld working-class education. One of the more recent examples of this is the government’s decision to cut the Union Learning Fund, which allowed working people to study and develop other skills through their unions. PEP stands to revitalise and extend political education to all, for free. By being available online, it also defies national borders.

PEP has sought to promote political education as a fundamental part of community organising. The project shifts the belief that education has to be a traditional top-down structure and positions it as an intergenerational, horizontal, accessible tool that serves as a remedy to the ills of today and allows us to plan for a better tomorrow collectively.

Collective pathways

In the age of social media, dominated by aesthetic infographics, Twitter echo chambers, algorithmic video recommendations and clickbait sensationalism, the individualistic ‘personal is the political’ perspective has, as Sivanandan warned, ‘tended in practice to personalise and fragment and close down struggles’. This is aided, of course, by the growing state-led censorship of radical thinking within schools, which seeks to impose a less political and critical approach to the oppression that surrounds us.

The left needs to be active in providing pathways to political education that are accessible and engaging. PEP, inspired by movements of the past that were invested in consciousness raising, is one model that can be adopted anywhere in the world, by anyone who seeks to engage and organise communities.

In order for the teachings of radical thinkers like Marx, Saïd, Fanon, Angela Davis and Rosa Luxemburg to be accessible, young people must feel political education is relevant to their lives. This is not about diminishing the political to personal experiences but starting from personal experiences to develop structural critiques of the world in which we live–always with an eye to changing it.

As Sivanandan explains:

The personal is the political is concerned with altering the goal posts, the political is personal is concerned with the field of play. The personal is the political may produce radical individualism, the political is personal produces a radical society.

Throughout history, this has taken place through the engagement of communities, by linking the work of left-wing revolutionaries with people’s everyday struggles. We must remind ourselves that knowledge is power only if it translates into collective organisation and action.

This article first appeared in issue #235, ‘Educate, agitate, organise’.

Shamime Ibrahim is a student, community organiser and youth ambassador in North Kensington