Slip slidin’ away—that is what tends to happen to pro-worker reforms in our economic system. Things are structured so that without constant vigilance and struggle on our part, gains are gradually undone. A case in point: overtime pay.

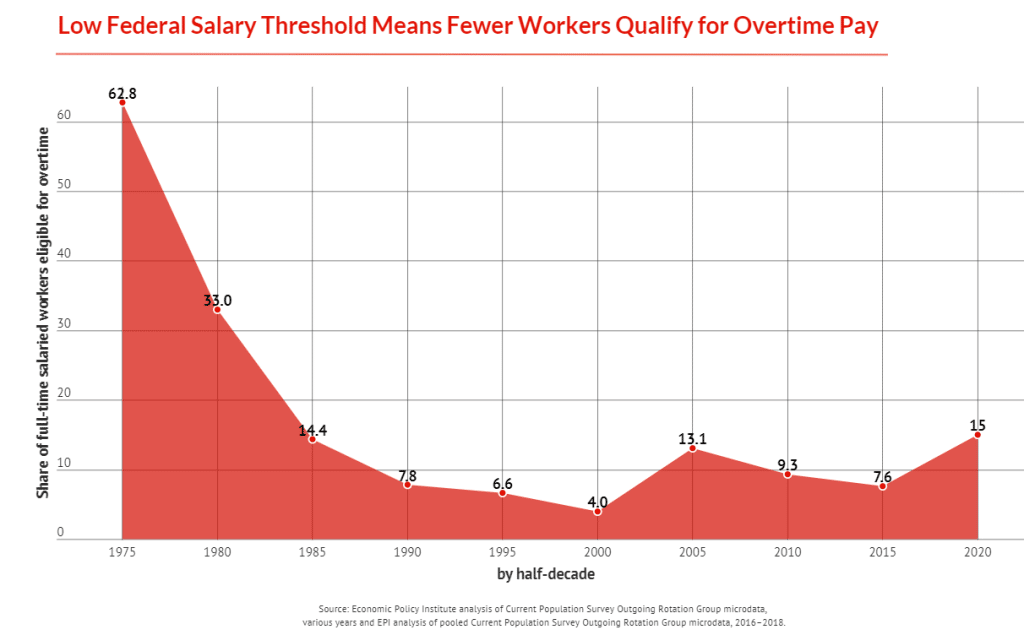

It wasn’t that long ago that most workers in the U.S. were eligible for time and half pay for every hour worked beyond a 40-hour work week. Employers didn’t agree to overtime pay out of the goodness of their hearts. They did it because worker organizing and activism pressured Congress to pass a labor law requiring, although with some important exceptions, the payment of overtime wages. Now, a significant number of workers no longer have the right to overtime pay. For example, in 1975 more than 60 percent of salaried workers automatically qualified for time and half pay. That share fell to a low of 4 percent in 2000 before slowly rising to 15 percent in 2020.

The law

The 1938Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) established the regulations for overtime pay. In broad brush, employees paid on an hourly basis were made eligible for overtime pay. More specifically, if they put in more than 40 hours of work in a week, they are to be paid 1.5 times their regular hourly wage for each extra hour worked. There were, of course, some notable exceptions—for example farm workers were not covered by the law and thus not eligible for overtime pay.

Coverage was then dramatically narrowed by a provision of the Fair Labor Standards Amendments of 1989. Small businesses, those reporting less than $500,000 in annual revenue and not engaged in interstate commerce, were made exempt from most wage and hour laws. As a result, tens of millions of workers lost their overtime eligibility.

The FLSA also covered salaried workers. Those who receive a salary below the U.S. Department of Labor’s minimum salary threshold were made eligible for overtime pay. Those who receive a salary above that threshold can be declared ineligible for overtime if their employer certifies that their primary duties place them in an “executive,” “administrative,” or “professional” category.

Separate from those three organizational categories, the FLSA includes an ever-expanding list of employment categories that are ruled ineligible for overtime regardless of salary earned. The list includes, for example, teachers, computer programmers, insurance claims adjusters, news editors, journalists, motion picture theater workers, and most delivery workers. As the sociologist Kimberly Bobo explains,

Many of these job categories are only “exempt” because employers’ groups have lobbied hard to have made them “exempt,” rather than because there is some intrinsic reason why the workers shouldn’t be provided overtime pay.

According to Marcus Baram, author of a four-part series titled “Who Killed Overtime?” published by the Capital & Main blog, the rules on overtime eligibility are so complicated that “the Labor Department’s own officials have admitted during congressional hearings on the subject that they have trouble understanding them.”

Salaried workers

As the following chart shows, there has been a dramatic decline in the percentage of full-time salaried workers who are automatically eligible for overtime pay. The main reason for the decline is that the federal government has repeatedly refused to raise the salary threshold. Inflation means that more and more salaried workers find themselves earning more than the threshold even if the inflation produces a decline in their real earnings.

The overtime threshold has only been changed two times since 1975. That year it was set at $155 a week or $8060 a year. President Jimmy Carter talked about boosting the threshold but, fearful of worsening inflationary pressures, never did. Finally, in 2004, after almost 30 years, the threshold was raised to $455 a week or $23,660 a year.

In 2016, the Obama administration sought to raise the threshold to $47,500, include a provision to automatically increase the threshold every three years, and restrict the ability of companies to exempt employees from overtime by giving them minimal managerial or professional responsibilities. But, dozens of industry groups and states sued to block the proposed changes claiming government overreach, and a federal judge ruled in their favor, killing the effort. As a measure of how far the threshold for eligibility for overtime work for salaried workers had fallen behind inflation, the $8,060 salary limit set in 1975 was the equivalent, adjusted for inflation, of $50,440 in 2014. By contrast the actual threshold remained at $23,660.

The last threshold increase came in 2019, during President Trump’s administration, when it was raised to $684 a week or $35,568 annually. The Biden administration is currently considering whether to pursue another increase in the threshold and, in line with the Obama administration plan, a requirement for future cost of living increases and restrictions on the use of management and professional designations to avoid payment of overtime.

Hourly workers

While the law granting overtime appears more favorable to hourly workers, they face their own challenges. For example, many companies, including the biggest, employ a number of strategies to cheat workers out of their earned overtime. These include requiring workers to work off-the-clock before or after their shifts, manipulating the clock-in and clock-out process, misclassifying employees as independent contractors, averaging hours workers over different weeks, and just plain old refusing to pay time and a half.

Wage theft continues to grow as a national problem because enforcement of overtime regulations is spotty due to a shortage of inspectors and penalties for violating the overtime law are insignificant. According to Baram,

The largest fine for the repeated or “willful” violation of minimum wage or overtime laws by a business is just $2,203 per incident. And even when inspectors find wrongdoing, they only assess monetary penalties in roughly half of cases, per Labor Department reports.

It is impossible to know how much money workers lose from this kind of wage theft, in part, because many workers are either unaware that they are being cheated or feel the costs of reporting their employer is too high. One study of wage theft—encompassing not only unpaid overtime but also unauthorized paycheck deductions as well as payment below the legal minimum wage—concluded that the total value of wages stolen from workers in 2017 topped $15 billion dollars, roughly comparable to that year’s dollar value of property crime.

What is to be done

First, we need to work with public school teachers to ensure that students get a good education in the realities of work under capitalism, which means at a minimum they need to learn about their workplace rights and how to defend them. Right now, high school economics classes, when they exist, spend way too much time praising market forces and “entrepreneurship.”

Second, we need to pressure state governments to improve their own standards. As with the minimum wage, state labor departments can improve upon federal standards. Several already do. For example, both California and New York have established higher overtime thresholds for their respective white-collar workers, making more of them eligible for overtime pay.

As Allen Smith notes in an employment law blog post, California has different thresholds for its salaried workers depending on the size of the company that employs them. The threshold is $1,120 a week or $58,240 annually for companies with 26 or more employees and $1,040 per week or $54,080 annually for companies with 25 or fewer employees. In contrast, New York has different thresholds depending on the location of the business. If it is in New York City the threshold is $1,125 a week or $58,000 annually), on Long Island or in Westchester County it is $1,050 a week or $54,600 annually, while in the rest of the state the threshold is $937.50 a week or $48,750 annually.

Third, we need to pressure President Biden to carry through on his promises to improve overtime regulations and increase the Department of Labor’s budget and investigative capacities. As Baram points out:

The Department of Labor has seen its roster of Wage and Hour Division investigators decline from 1,600 inspectors in 1980 to just 725 inspectors in early 2022, a 50-year low — even as the size of the workforce has increased sharply during that time.

“A lot of the investigators that I knew in the agency felt like that they were just barely treading water,” a former administrator told Bloomberg Law. “They really weren’t in a position to effectively do their job, because they were so understaffed.”

Certainly, none of the above will be easy, but the organizing itself is important for sharpening our collective understanding of contemporary class and policy-making dynamics and building the relationships needed to establish the strong, grounded, action-oriented, community-labor coalitions required for winning real change.