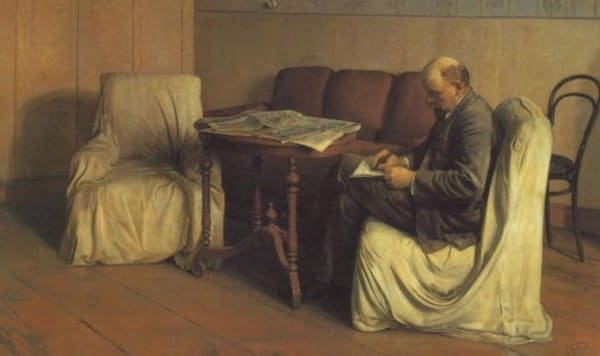

As Lenin prepared to understand the First Great Slaughter of the twentieth century, he spent from September to December 1914 absorbing Hegel’s The Science of Logic (1813). Humphrey McQueen begins a six-part exploration of why Lenin thought he had to do so. This first installment, Dialectical Reasoning: ‘The Science of Interconnectedness’1 shows why Hegel is still not ‘a dead dog.’

Without German philosophy […] particularly that of Hegel, German scientific socialism — the only scientific socialism that has ever existed — would never have come into being. Without the workers’ sense of theory this scientific socialism would never have entered their flesh and blood as much as is the case.

— Frederick Engels, 1875.2

How often do we hear: ‘Philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways; the point is to change it’?3 Known as ‘Thesis Eleven,’ Marx’s challenge comes at the end of a couple of pages of rough notes in preparation for a 65-page chapter on Ludwig Feuerbach in The German Ideology.4

How often is ‘Thesis Eleven’ seized on as an excuse for not undertaking research and critical analysis? How many of those who sprout that slovenliness go on to read those pages? Marx warns why such tasks are essential: ‘There is no royal road to science, and only those who do not dread the fatiguing climb of its steep paths have a chance of gaining its luminous summits.’5

This six-part series highlights that there never is a choice between interpreting and changing. That rule applies to every action by everybody. At one extreme, some people are refusing vaccination because that is how they interpret the word of their god. As revolutionaries, we historical materialists cannot interpret the world with any degree of accuracy without changing it. Equally, we learn how better to change the world to achieve socialism as we learn how better to interpret our contributions to the changes we effect and affect. The mindless militancy of megaphone Marxists has no place in weaving tactics into strategies.

In Imperialism, Lenin had to interpret socio-economic conflicts at a moment of maximum tumult. The object of this inquiry differs from both the substance and pace of change taken up in two of his previous analyses. The Development of Capitalism in Russia (1899) sought the outcome of socioeconomic changes running over four decades, which he interprets in order to ground strategies for revolutionary change. Materialism and Empirio-Criticism (1908) covers a similar time-period but for interplays between discoveries in the natural sciences and speculative philosophizing about their significance. Here, Lenin rebuts challenges to materialist dialectics. Parts Two and Three in this series will examine those works to see why, in 1914, he turns to Hegel’s The Science of Logic as one more weapon in his campaigns against the Great Slaughter and its effects. Materialism and Empirio-Criticism (1908) will be the subject of Part Two, while Part Three begins from his The Development of Capitalism in Russia(1899) as a side road into the monopolising stage of capitalism, which Bukharin, and then Lenin, call Imperialism. Part Four turns our attention towards approaching that stage as one of revolution and counter-revolution with the varieties of fascism as open class dictatorship into the early 1950s, before contrasting that phase with the covert ones in today’s surveillance state. Part Five tracks the momenta of monopolising capital from the Second Great Slaughter across the dominance of the U.S. corporate-warfare state into the mid-1970s. Part Six ponders whether Monetarism, Globalisation, Financialisation, Neo-Liberalism and rentierism have been phases leading into a higher stage of monopolising capitals.

An Hegelian turn

Lenin’s turning to Hegel’s The Science of Logic in September 1914 has two broad sources. The more obvious one is the link to Marx and Engels starting from their polemics against the Young Hegelians, The Holy Family (1844) and The German Ideology (published 1932). Although the latter work let them ‘settle accounts with our former philosophical conscience,’6 they never sought to exorcise the Geist(‘Spirit’) of Hegel’s dialectical method. Indeed, they return to its logic throughout their lives.7

For instance, while drafting A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (CCPE) (1859), Marx tells Engels how he is

discovering some nice arguments. E.g. I have completely demolished the theory of profit as hitherto propounded. What was of great use to me as regards method of treatment was Hegel’s Logic at which I had taken another look by mere accident, Freiligrath having found and made me a present of several volumes of Hegel, originally the property of Bakunin. If ever the time comes when such work is again possible, I should very much like to write 2 or 3 sheets [i.e. 32-48 pages] making accessible to the common reader the rational aspect of the method which Hegel not only discovered but also mystified.8

That time never came. Even though Marx mentions Hegel only twice in A Contribution…,9 we can construe his intentions for that pamphlet from his long unpublished ‘Introduction’ to A Contribution. Its ‘Preface’ stayed silent on class struggle in order to evade the censor.10 That absence is used to misrepresent Marx as a technological determinist, denying his materialist dialectics in the ‘Introduction.’11

When Marx expands A Contribution into the opening chapters of the first volume of Capital (1867), he remarks that he has ‘coquetted with the mode of expression peculiar to Hegel.’ He had done more than to flirt with the prose style of the ‘dead dog.’12 Three instances of Hegel’s hand can be deciphered from the following brief passage, which will be broken up to insert the influences in italics:

It is in the world market that money first functions to its full extent as the commodity whose natural form is also the directly social form

Forms move between physical and class relationships since no category is fixed or impermeable;

of realisation of human labour in the abstract.13

‘abstract’ means to abstract from particulars, not to float above them;

It is only as world-money that money’s mode of existence becomes adequate to its concept.14

Only when a form is fully developed can it come into full agreement with its Concept.

Hegel’s treatment of forms, the abstract against the concrete, and the Concept will be taken up below.

Given the intricacies of so much of what Marx carries forward from Hegel, it is no wonder that Lenin exclaims

…it is impossible completely to understand Marx’s Capital, and especially its first chapter, without having thoroughly studied and understood the whole of Hegel’s Logic. Consequently, half a century later none of the Marxists understood Marx!!15

Or is it truer to say that no one had fully understood the opening three chapters? How many do today? How many get beyond them?

On not reading Hegel

Jokes about Marxists who never finish even the first volume of Capital are legion. The ‘Received Opinion’ is that ‘Marx is unreadable.’16 That conventional wisdom is applied in spades against Hegel. Where the allegation proves true for either, the reasons are quite different.

When we encounter passages in Marx which demand our total attention we are being invited into the complexities of accumulation for the social reproduction of capital on expanding scales.17 His account is no more complicated than the object of his critical analysis. A further obstacle to get around is that Marx had not been able to bring all of volumes II and III to the polished state of his revised editions of the first volume. As editor, Engels decided to interfere as little as possible so that we might receive Marx in his own words. One result is that we encounter convoluted syntax; pronouns which do not always refer to the closest previous nouns; sentences with parenthetical clauses inside parenthetical clauses; and too few full-stops, paragraph breaks and sub-headings.

Hegel is another matter. He will write pellucid prose for page after page, embellished with wit. Then he whacks us with a paragraph in which his vocabulary is comprehensible only to those who hope that they already know at what he is driving:

215. The Idea is essentially a process, because its identify is the absolute and free identity of the notion, only in so far as it is absolute negativity and for that reason dialectical. It is the round of movement, in which the notion, in the capacity of universality which is individuality, gives itself the character of objectivity and of the antithesis thereto; and this externality which has the notion for its substance, finds is way back to subjectivity through its immanent dialectic.18

Such rolling conundrums are why Lenin could describe a segment on ‘Subjectivity’ in The Science of Logic as the ‘Best means for getting a headache.’ Yet he accepted that he would have to go over and over the passage until he grasped its significance.19 The patience of nine cats is called for if we are to reveal the ‘rational kernel’ of the ‘notion’ as boundless activity, the punctum saliens [starting point] of all vitality.’20 Hegel finds movement everywhere.

Far from all of Hegel’s Logic and The Science of Logic is burdened with self-referential terminology, and so does not need to be ‘translated into prose,’ as Marx quipped in 1843.21 For instance, we can savour Hegel’s illumination of the pre-Islamic religions of Persia in Phenomenology of Spirit.22

A minor hurdle to understanding what Hegel intends by the ‘Idea’ is the two meanings we give to ‘Idealism,’ with or without a capital-I. In philosophy, capital-I Idealism refers to how one perceives the world and how we come to know about it. Those Idealist treatments of being (ontology) and of knowledge (epistemology) are as distinct from being ‘idealistic’ in an ethical sense as Marx’s philosophical Materialism is remote from the pursuit of worldly goods, or any of the Deadly Sins.

The ‘Idea’

Plato was an Idealist, but not all Idealists are Plato. Hegel certainly wasn’t. He saw himself closer to Aristotle who approaches the Idea through its actualities in the world as shown in his lectures on generation, insomnia and physics. ‘Knowing’ and ‘Being’ go hand-in-hand for Hegel and Aristotle.23

For them, the Idea is always being realized in this world. Their treatment of ‘Form’ differs from Plato’s Ideal Forms which are pre-existent and unchanging. For Plato, all the beds and tables made by us humans are poor copies of the Ideal Forms of the bed-in-itself and the table-in-itself.24 Hegel pictures the world moving in the opposite direction. Human action is how the Idea manifests itself over time so that the Absolute can attain Perfection.25

In 1814, while still a school teacher, Hegel confides his ambition to a friend:

You know that I have had too much to do not merely with ancient literature, but even with mathematics, latterly with the higher analysis, differential calculus, to let myself be taken in by the humbug of Natural Philosophy, philosophising without knowledge of fact and merely by force of imagination, treating mere fancies, even imbecile fancies, as Ideas.26

If his ‘Idea’ is more than a ‘fancy,’ more than some flight of the imagination, in what ways does he connect the Idea to the external world? His answer goes some way towards a materialist explanation despite his framing the issue within the unfolding of a god-centered purpose. His god realizes its Perfection through the interactions of ‘Necessity’ and ‘Freedom,’ which become possible only by ‘the activity of man in the widest senses.’27 Far from Hegel’s accepting that god will remain in the end what it had been at its beginning, he pictures god as a work-in-progress. That work requires human activity without our becoming aware of its purpose.

Confirmed Christians will be as perplexed as dyed-in-the-wool atheists to read that ‘the vast congeries of volitions, interests and activities, constitute the instruments and means of the world-spirit for attaining its object…’28 Hegel has human beings bring the Absolute into full agreement with his Concept of it, or as he would say, of itself.

By attending to the labour required for those processes, Hegel moves some way towards history as ‘sensuous human activity,’ as social practice. For historical materialists, if humankind has an essence it is our remaking ourselves as individuals and as a species through activities, mental and physical.

Drawing on the Scottish Enlightenment, Hegel also proposes that the creation of needs plays its part in the transition from ape to man:

An animal’s needs and its ways and means of satisfying them are both alike restricted in scope. Though man is subject to this restriction too, yet at the same time he evinces his transcendence of it and his universality, first by the multiplication of needs and means of satisfying them, secondly by the differentiation and division of concrete need into single parts…29

Marx’s anthropology explores how ‘historically developed social needs … become second nature,’ forming a human type ‘as rich as possible in needs.’ He locates that expansion within the need that capital has to expand by realizing the value present in commodities of every kind, whether boots, bibles or brandy.30

On the contrary

No assumption about Hegel’s logic is more widely known and misunderstood than his use of dialectics in regard to ‘contradiction.’ The Philosophy 101-version has a thesis being overtaken by its antithesis to end in a synthesis. And that’s all you need to know about the ‘contradiction,’ comrade.

Generations of Hegel scholars have pointed out that no such formulation is to be found in his writings.31 To get beyond that simplification, we need to attend to two issues: (a) with what kind of ‘contradiction’ are we dealing?; (b) how do the three parts of the dialectic act on each other?

First, the English word ‘contradiction’ derives from ‘contra-‘ as ‘against,’ and ‘-diction’ meaning ‘to speak.’ The Formal Logic of Aristotle includes a Law of the Excluded Middle. Propositions which assert direct opposites cannot both be true at the same time. If A = A, A cannot equal non-A. The sentences that ‘Porter is a rapist’ and ‘Porter is not a rapist’ contradict each other.32 Confined to the realm of propositions, Porter is either a rapist or he is not. A contra-diction between utterances tells us next-to-nothing about any issue of substance.

Secondly, the components of Hegel’s triad do not encounter each other like billiard balls colliding only to bounce off in their own directions. Each element has its inner movements; when the elements come into contact they interpenetrate; they go on in their new forms to repeat the circuit.

A rigid dichotomy of ‘Dead or Alive’ — of either A or non-A — has no place in describing the animate world. Although we speak of death being instantaneous from a stroke, dying is always a process, with vital signs ebbing away, while our hair and nails keep growing for weeks, underpinning the belief in vampires as the living dead.33 Engels rejoices in the confirmation of an egg-laying mammal — the ‘Australian Paradox’ — the platypus: ‘one rigid boundary line of classification after another has been swept away in the domain of organic nature.’34 Were that not the case, the evolution of species would require divine intervention.

Although the laws of physics apply to living matter, we must never collapse the social into the physical. Engels wrote to Marx about a Russian agronomist who ‘went astray after his very valuable discovery, because he sought to find in the field of natural science fresh evidence of the rightness of socialism and hence has confused the physical with the economic.’35

No keener account of contradiction exists than Mao’s On Contradiction (1937). Were one not a materialist, one could suppose than he had channeled Marx to provide ‘2 or 3 sheets making accessible to the common reader the rational aspect of the method which Hegel not only discovered but also mystified.’36

Mao explores the ways in which material actualities find expression through shifting levels within principal and secondary contradictions, each with its principal and secondary aspects. He had honed this method in his 1927 Report on an Investigation of the Peasant Movement in Hunan which he conducted at the same time as the launch of the Autumn Uprising there and setting up the first revolutionary base. With whom was it possible to form alliances?, and on what terms? These, indeed, were matters of life or death.

Some contradictions are antagonistic, like those with the comprador bourgeoisie and the invading Japanese Militarists. Both require class violence to resolve. Disputes with a national bourgeoisie can be handled by other forms of struggle. Later in the war against the Japanese, it became possible to form alliances with their imperialist rivals. In 1937, the Communists were fighting on two fronts. Inside the Party were those who could not see how to unify theory and practice; and, at the same time, the Party had to develop tactics and strategies against Generalissimo Cash-my-cheque and the Japanese militarists. By the end of that year, the Nationalists and the Communists agreed to concentrate their forces against the invaders. Hence, the Party’s need to distinguish principal from secondary contradictions were hourly events. In addition, what was possible in Shanghai was not the same as in the mountains of Yunan. What was possible at harvest time there was not the same as in winter.

Late in February 1957, four months after Khrushchev’s attack on Stalin, Mao further develops distinctions between antagonistic and non-antagonistic conflicts in “On the Correct Handling of Contradictions among the People.”

In unifying interpretation with change, Mao rescues the rational aspect from Hegel’s mystification of the dialectic. His emphasis on the levels of contradiction allows for their simultaneous operations at different speeds and intensities. Accepting their multiplying and mutating contexts makes it possible to extract the concrete from the abstract.

Abstract/concrete

Hegel’s treatment of ‘concrete’ and ‘abstract’ reverses everyday usage where a piece of data is prized as ‘concrete,’ whereas even a generalisation is suspected of being ‘abstract,’ a mere ‘theory,’ not grounded in everyday experience and lacking the endorsement of ‘common sense.’ For Hegel, it is the stand-alone datum which is abstract. It becomes ‘concrete’ only in its several, multiplying and mobile contexts. He illustrates his counter view of the concrete with an example from Aristotle: ‘The single members of the body are what they are only by and in relation to their unity. A hand, e.g. when hewn from the body is … a hand in name only, not in fact.’37 He extends this treatment of the ‘concrete’ past the manual to the domains of thought:

Hence the meaning to be attributed in what follows to ‘subjective’ or ‘objective’ in respect of the will must each time appear from the context, which supplies the data for inferring their position in relation to the will as a whole.38

Although Hegel is here soaring beyond the physical, he never abandons his commitment to empirical investigation. Accordingly, to treat contradiction or dialectic as disconnected propositions is itself anti-dialectical.

It is not that a maxim such as ‘One divides into two’ is wrong as far as it goes but that it is mechanical because it is used in the singular. To be open to dialectical reasoning, the constituents of a contradiction must interact.39 Like the actualities of existence, they never all do so at the same moment, at the same pace, or with the same intensity as each other. Take the key conflict of labour versus capital. The agents of capital buy timed units of labour-power which is subsumed into variable capital, the sole source of added value. Closely related to that circuit is how use-value and exchange-value combine to be the commodities in which surplus-value is present.

A Logic for the New Science

Hegel’s logic does not deal primarily with statements about the world. Rather, he is concerned with how it operates. To provide answers, he has to explain how exactly the dialectic works. In line with Aristotle, he insists on activity for his theory of knowledge as much as for empirical investigation. Their combination carries our perceptions towards greater degrees of relative truth regarding the actualities outside our heads.

By 1811, Hegel has convinced himself that Formal Logic had long been a dead end for the advancement of knowledge. He sets out to develop an alternative:

a knowledge of the facts in geometry and philosophy is one thing, and the mathematical or philosophical talent which procreates and discovers is another: my province is to discover that scientific form, or to aid in the formation of it.40

He composes The Science of Logic and the shorter Logic because he recognises that human understanding needs a method which can catch up with 2,000 years of social upheaval and earthly revelation. Thinking about logic had not taken a step forward since Aristotle, leaving it all the more in need of a thorough overhaul; for when Spirit has worked on for two thousand years, it must have reached a better reflective consciousness of it own thought and its own unadulterated essence.41

Here again is Hegel’s Idealist terminology. Yet he is as adamant in his rejection of Kant’s ‘Idealism’ as he is of Aristotle’s Formal Logic. In support of his rejection of both, Hegel is heir to a long if interrupted approach, one stretching back to the first astronomers and to Aristotle’s investigations of the physical world before Medieval theologians petrified his legacy into their Scholasticism.

The practices to which since only the 1830s we have given the collective noun ‘science’ got a fresh start from new generations of European astronomers — Copernicus, Galileo, Tycho and Marx’s hero, Kepler. Francis Bacon spelt out the new order in 1620 by exhorting his readers to seek truth in the book of nature, as Aristotle did, and not rely the edited versions of his lectures.42 ‘Further Still!’ displaced ‘No further!’ in the explorations of nature while the method for making sense of them, singly or collectively, remained stuck at ‘No Further!’ (non plus ultra). Logic had been mummified.

Mathematics

Mathematicians offered one means to regularize the discoveries of science that were bursting through the straightjacket of Formal Logic.43 In 1637, Rene Descartes’s integration of algebra and geometry provided a means to describe the physical world. Fermat and Blaise Pascal laid foundations for probability theory to bring chance within the orbit of order.44 Newton and Leibniz devised the calculus in the early 1700s to track how incremental changes could result in a qualitative transformation.45

All five kept god as integral to their thinking — Pascal’s ‘Divine Wager.’ In 1774, Euler rattled off ‘a+ bto the power of n over n = x‘ as a proof that god exists. The break was proclaimed in 1812 when Laplace tells Napoleon that he has no need for the god hypothesis in his Celestial Mechanics.46

Although Hegel studied the calculus, he never got far beyond thinking of mathematics as limited to quantity and measure, and so never expected to integrate his Logic with the equations of Euler, Gauss, Laplace and Lagrange that were making sense of a world in flux.47 Marx, by contrast, will cover 1,000 pages on the calculus to help him conceive how one mode of production could become a qualitatively different one;48 specific to the capitalist mode, he had to explain how simple reproduction became accumulation for reproduction on expanding scales, and to understand how that metamorphosis leads through over-production to crises as booms turn into busts, only to clear the way for renewed cycles of reproduction on expanding scales.49

Discovering discovery

Despite Hegel’s aversion to mathematics as a rival to Speculative Philosophy, through his writings we meet a ‘mighty thinker’ who has absorbed Adam Smith on commercial society, along with the impact of the English, American and French Revolutions, someone who has an encyclopedic knowledge of several millennia of human endeavor, and is cognizant that ‘common sense’ is being discarded throughout the life and other physical sciences.

Even a random selection of the discoveries and technological innovations between his birth in 1770 and the 1813 publication of The Science of Logic shows why he set out to replace Formal Logic with a method adequate to the comprehension of those social and scientific upendings: oxygen against phlogiston, bringing an end to the epoch when alchemy had seemed necessary; the identification of nitrogen; Dalton’s atom; parts of the brain for different functions; heat as motion; electricity’s relation to magnetism; the age of the earth beyond the Biblical 6,000 years and the solar system formed out of gases, so that the universe was no longer quite as god had created it out of nothing. In technologies came bleaches for textiles, Whitney’s gin, gas lighting, canned food, inoculation and steam-powered transport.

Hegel does not follow Aristotle, Goethe or von Humboldt in experimentation. Indeed, he advises astronomers to study his Logic and not to waste their time seeking an eighth planet (Neptune). The library is his laboratory and so he is remembered as a philosopher of science, of history and of the law.

Philosophy: Theology

These days, Departments of Philosophy are debating societies. That marginal role is at odds with their glory days when ‘Natural Philosophy’ had been synonymous with ‘science’ as the quest for understanding in every sphere. As late as 1835, Andrew Ure could call his account of Britain’s economy, The Philosophy of Manufactures. The limited role we give to ‘philosopher’ today is one more measure of how materialism has triumphed over god-bothering and other kinds of speculation. Notwithstanding countless reversals, the Idealists have never stopped conjuring up new forms of a soul in which consciousness can dwell safe from the messiness and massiness of the being and doing that make thinking possible.

To refer to Hegel as a ‘philosopher’ is licensed by the title of two of his major works, The Philosophy of Right and The Philosophy of History. Yet Hegel saw himself as a Theologian even while under attack from those whom we today would characterize as a Fundamentalist wing of Prussian Lutheranism, the Pietists. Those true believers had no better understanding of his Theology than we might on first hearing that he saw himself as the Historiographer of the Absolute.

Hegel summarises his job description in the concluding sentence of The Philosophy of History:

…what has happened, and is happening every day, is not only not ‘without God,’ but is essentially His work.50

Thus, Hegel’s Absolute is the Artificer, the Being behind everything that happens, and not just the Architect behind creation.51 This view of the world might become a tad clearer if we ‘translate’ its terms into those of historical materialism:

…what has happened, and is happening every day, is not only not ‘without human labour,’ but is essentially our work.

We extracted a ‘rational kernel’ by breaking through Hegel’s mystical carapace. To do so involved more than standing him on his head.

When the Young Hegelians, including Marx and Engels, took up Feuerbach’s criticisms of Hegel’s god-centered universe, they had none of the difficulties we endure in deciphering his terms. They had been weaned on its assumptions and vocabulary. Engels, for instance, spent his free time between the ages of eighteen and twenty composing Lutheran hymns.52 Next year, he penned attacks on Schelling’s promotion of a mystical Christianity against Hegel’s version of the Absolute, to which he still adhered. Then, in 1841, Satan said: let Feuerbach be — ‘and all was light.’

The title of the pamphlet that Engels wrote in 1886, Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of German Classical Philosophy, should be the ‘Outcome’ (der Ausgang) rather than ‘End,’ since Feuerbach’s criticism of Hegelian Idealism was both the outcome of Idealist traditions but also a starting point for the historical materialism developed by Marx and himself. Hegel, of course, is no closet historical materialist. Yet neither is he an Idealist in the manner of the Platonists or the Pythagoreans whose current followers contend that only numbers are real.

No break is completed in an instant. In 1843, Marx acknowledges that ‘we continue to operate in the sphere of theology, however much we may “operate critically” against it, and within it.’53 Today’s historical materialists are no longer stuck there. Rather, we have to make an effort to think theologically if we are to extract the ‘rational kernel’ from within Hegel’s system. One barrier to our coming to grips with his Philosophical Idealism is that, as atheists, we have trouble of thinking in terms of any kind of god, souls and miracles.

Hegel’s version has nothing to do with an Old Man with a Beard who maintains a personal interest in each of us. Hegel’s god realizes itself through four Epochs of human activity, which he names the Oriental, the Greek, the Roman and the German, each with a geo-physical basis.54 If his schema of Epochs and Worlds seems to foreshadow Marx’s modes of production, by now it should be obvious that their approaches have different dynamics. Hegel’s determinants are physical and cultural against the Marx’s critical analysis of social reproduction which draws on plundering the wealth of nature. In addition, the two systems also have different dynamics for their inner motion. Hegel accepts that ‘the Spirit’ must manifest itself through human action. For Marx and Engels, our deeds are entirely of this world, taking effect through struggles between and within social classes.

It ain’t necessarily so

After Galileo had seen through the Milky Way in 1610, researchers in every field faced the same question: how are we to make sense of a world which does not align with ‘common sense’? As Marx puts it: ‘It is one of the tasks of science to reduce the visible and merely apparent movement to the actual inner movement.’55 The fashioning of that method has both conceptual and empirical components. We have to get beyond appearances without wafting off into New Age humbuggery.56

Hegel insists that what we have ‘to investigate and grasp in concepts’ are ‘not the formations and accidents evident to the superficial observer…’57 Rather, ‘the great thing is to apprehend in the show of the temporal and transient the substance which is immanent…’58 Hegel thus prepares a way for us to think ourselves out of Kant’s claim that we could never know a ‘thing-in-itself’ because all we can know of externals are our sensations. That limit condemns us to second-order conclusions.

Hegel’s method had to be demonstrated and not just elaborated in writing. Only social practice could break through the surface to the inner motion.59 For instance, two years before his death from cholera in 1831, new generations of microscopes allowed researchers to see inside cells, identifying a nucleus by 1839 and then mitochondria by 1890.60 William Perkin’s production of coal-tar dyes in 1857-8 allowed Engels to gloat: ‘If we are able to prove the correctness of our conception of a natural process by making it ourselves, there is an end to the Kantian ungraspable “thing-in-itself.”’61

However, more is demanded of dialectical reasoning than an initial lifting of the veil. How are we to make sense of the little we can glimpse beneath the level of appearance on our first step? To proceed, we have to re-examine the phenomenal level in light of what we have learnt of inner motion. Better informed, we delve again and return to the surface in a ceaseless spiral towards ever higher levels of never more than relative knowledge. If all goes well, each circuit should yield a richer understanding not only of appearance, and of inner motion but also of the interplays between them, in short, of dialectical contradictions and inter-connectedness.

No matter how much we learn, our knowledge remains relative. One reason is that the objects of our inquiries are not standing still. The universe expands. Climates change. Viruses mutate. We are White Rabbits, forever running late in our investigations of nature. In social domains, our situation is worse because it is better: better because human history is the product of our labour; worse because the divisions of labour and of capital divert thinking about our practices into self-interested explanations.

For Marx and Engels, a dialectical context is one of structured dynamics, not of dynamic structures, neither static structures nor unfettered dynamics as in the randomness of chaos. ‘Chance and caprice,’ along with ‘zig and the zag,’ appear in their accounts of human activity,62 but within patterns and regularities. Since they never are, ‘Every law is tendential,’ as Marx reiterates, ‘all other things being equal.’63 Dialectical reasoning dispels Formal Logic.

More than a conclusion

No one need study Hegel’s The Science of Logic as thoroughly as Lenin did before venturing into his Imperialism. What is impermissible is either to pass judgement on it, or to expect to act out its politics, without the modesty of pondering why Lenin decided he had to absorb Hegel’s 800 pages in order to interpret the impact from the Great Slaughter. Change and interpretation were never alternatives for him. The practice of his politics indicates how to integrate them.

For us to begin to interpret the changes during the 100 and more years since 1914-16 will leave us grappling with more of Capital than its first chapter. Success in practice and theory will follow by recognising why Lenin needed to deepen his appreciation of Hegelian dialectics if he were to understand even those fifty pages.

More telling than Lenin’s self-criticism is his encouragement of ‘the workers’ sense of theory’ in the wake of the chaos from four-and-a-half years of revolution, intervention and civil wars. He calls on the Bolsheviks for more than action, action and again action. To make any change effective in laying the foundations for socialism, he proposes that

…the editors and contributors of Under the Banner of Marxism should be a kind of ‘Society of Materialist Friends of Hegelian Dialectics.’64

Of course, this study, this interpretation, this propaganda of Hegelian dialectics is extremely difficult, and the first experiments in this direction will undoubtedly be accompanied by errors. But only he who never does anything never makes mistakes.

Sources on Hegel

- Hook, Sidney, From Hegel to Marx Studies in the Intellectual Development of Karl Marx (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1962).

- James, C. L. R., Notes on Dialectics Hegel, Marx and Lenin (London: Allison & Busby, 1980).

- Marcuse, Herbert, Reason and Revolution Hegel and the Rise of Social Theory (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1955).

- Pinkard, Terry, Hegel A Biography (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000).65

- Plekhanov, George, The Development of the Monist View of History (Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1956), 96-102, 136-40 and Appendix I.

- Popper, Karl, The Open Society and its Enemies, volume 2, (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1966), chapter 12.66

- Taylor, Charles, Hegel (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1975).67

Notes:

- ↩ Frederick Engels, “The Dialectics of Nature,” Marx-Engels Collected Works (M-ECW), volume 25 (New York: International Publishers, 1987), 356.

- ↩ Frederick Engels, “Supplement to the Preface of 1870 for ‘The Peasant War in Germany’,” M-ECW, vol. 23, (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1988), 630.

- ↩ Karl Marx, “Theses on Feuerbach,” M-ECW, vol. 5 (London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1976), 5 and 8.

- ↩ Marx and Engels, “The German Ideology,” M-ECW, vol. 5, 27-93; they wrote The German Ideology in 1845-46, though it was not published until 1932.

- ↩ Karl Marx, “Preface to the French Edition,” Capital, volume 1 (London: Penguin, 1976), 104; see Karl Korsch, Marxism and Philosophy (London: NLB, 1970), 82-3; for the effort needed to change the world see August H. Nimtz Jr., The Ballot, the Streets — or Both: From Marx and Engels to Lenin and the October Revolution (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2017).

- ↩ Karl Marx, A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (CCPE) (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1970), 22.

- ↩ Engels provided a guide to the shorter Logic in a letter to Conrad Schmidt, November 1, 1891, M-ECW, vol. 49, (New York; International Publishers, 2001), 286-7.

- ↩ Marx to Engels, January 16, 1858, M-ECW, vol. 40 (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1983), 249.

- ↩ Marx, CCPE, 20 and 207. Hegel is more present in the reviews that Engels pens in an effort to publicise his comrade’s discoveries, where he points to Marx’s historical-logical method, 219 and 222-5.

- ↩ Arthur M. Prinz, “Background and Ulterior Motive of Marx’s ‘Preface’ of 1859,” Journal of the History of Ideas, 30, no. 3 (1969), 437-50.

- ↩ Marx’s use of ‘conditioned’ (bedingen) in CCPE, 20-21, has to be distinguished from his use of ‘determined’ (bestimmen) as Bertell Ollman points out, Alienation, Marx’s conception of man in capitalist society (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976), 280, n. 23.

- ↩ Marx, Capital, I, 102-3.

- ↩ Marx, Capital, I, 142 and 150. Marx begins by making simplifying assumptions which he relaxes across the three volumes, controversially, to reveal how the value of a commodity becomes its market price.

- ↩ Marx, Capital, I, 240-1.

- ↩ V. I. Lenin, Philosophical Notebooks, Collected Works (CW), vol. 38, (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1972), 180.

- ↩ See my “The ‘Unreadable’ Marx.” [web]

- ↩ Marx, Capital, II, especially chapter 21.

- ↩ G. F. W. Hegel, Logic, (The First Part of the Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences in Outline) (Milton Keyes: Digireads, 2013), 191.

- ↩ Lenin, CW, vol. 38, 176.

- ↩ Hegel, Logic, 162.

- ↩ Karl Marx, “Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Law,” M-ECW, vol. 3, (London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1975), 7.

- ↩ G.W.F. Hegel, Phenomenology of Spirit (Oxford: Oxford University Press , 1977), 416-8.

- ↩ Hegel, Logic, 142-3.

- ↩ Plato, The Republic (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1987), 422-6.

- ↩ Patrick Masterson, Atheism and Alienation A Study in the Philosophical Sources of Contemporary Atheism (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1973), 53-8.

- ↩ Quoted Hegel, Logic, 7-8; Edward Grant, A History of Natural Philosophy, From the Ancient World to the Nineteenth Century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007) chapters 9 and 10.

- ↩ G. W. F. Hegel, The Philosophy of History (London: Encyclopedia Britannica, 1952), 163.

- ↩ Hegel, The Philosophy of History, 163-4.

- ↩ Hegel, The Philosophy of Right, 66.

- ↩ Karl Marx, Grundrisse (London: Penguin, 1973), 407, 409-10 and 825; Karl Marx, “Wage-Labour and Capital,” M-ECW, vol. 9 (London, Lawrence & Wishart, 1977), 221; Michael A. Lebowitz, “Capital and the Production of Needs,” Science & Society, 41, no. 4 (1977-8): 430-47.

- ↩ Walter A. Kaufmann, “The Hegel Myth and Its Method,” The Philosophical Review, 60, no. 4 (1951): 459-486.

- ↩ Karate Master, Marxist and erstwhile Professor of Philosophy at the University of Melbourne, Graham Priest, gained a following by deploying Symbolic Logic to hold that in certain cases, the negation of a true statement is also true, see Greg Restall, “Graham Priest,” Graham Oppy & N. N. Trakakis (eds) A Companion to Philosophy in Australia & New Zealand (Clayton: Monash University Publishing, 2010), 462-4.

- ↩ Engels; Sherwin Nuland, How we die, Reflections on Life’s Final Chapter (New York: Vintage, 1994).

- ↩ Frederick Engels. “‘Preface’ (1885) Anti-Duhring,” M-ECW, vol. 25, 14.

- ↩ Engels to Marx, December 19, 1882, M-ECW, vol. 46 (New York: International Publishers, 1992), 412.

- ↩ Mao Tse-tung, “On Contradiction,” Four Essays on Philosophy (Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1966), 23-78. Fred Halliday reports that Karl Korsch ‘wrote an introduction to a planned volume of Mao Tse-Tung’s essays, stressing their theoretical originality,’ “An Introduction,” Korsch, Marxism and Philosophy, 20.

- ↩ Hegel, Logic, 192; singled out by Lenin, “Philosophical Notebooks,” CW, vol. 38, 202.

- ↩ Hegel, The Philosophy of Right, 18.

- ↩ In what ways does this characteristic differ from Leibniz’s Monad? G. W. Leibniz, Philosophical Writings (London: J.M. Dent, 1934), 7-19; Roy T. Cook, “Studia Monads and Mathematics: The Logic of Leibniz’s Mereology,” Leibnitiana, 32, no. 1 (2000): 1-20.

- ↩ Hegel quoted, Logic, 7.

- ↩ G. W. F. Hegel, The Science of Logic (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1927), 62-63.

- ↩ Alexandre Koyre, Closed World to Infinite Universe (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1957); and Newtonian Studies (London: Chapman & Hall, 1965), Paoli Rossi, Philosophy, Technology and the Arts in the Early Modern Era (New York: HarperTorchbacks, 1970), and Francis Bacon from magic to science (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1968); Herbert Butterfield, The Origins of Modern Science (New York: The Free Press, 1965); Lisa Jardine, Ingenious Pursuits Building the Scientific Revolution (London: Abacus, 2000).

- ↩ Dirk J. Struik, Concise history of mathematics (London: Bell, 1954); for an obituary of this Dutch Marxist, Isis, 93 (3) (2002): 456-9; G. T. Kneebone, Mathematical Logic and the foundations of mathematics (New York: Van Nostrand, 1963); Alexandre Koyre, Metaphysics and Measurement(London: Chapman & Hall, 1968); Witold Kula, Measures and Men (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986).

- ↩ Cark B. Boyer, A History of Mathematics (New York: Wiley International, 1968) 397ff and 463ff; for developments in Hegel’s lifetime, Ian Hacking, The Taming of Chance (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990).

- ↩ Carl B. Boyer, The History of the Calculus and its Conceptual Development (New York, Dover 1959), chapter 5.

- ↩ E. T. Bell, Men of Mathematics (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1953), volume one, 160 and 198 in this less than reverent survey of the lives and contributions of the great.

- ↩ Ernst Kol’man and Sonia Yanovskaya, “Hegel and Mathematics,” Karl Marx, Mathematical Manuscripts (New York: New Park, 1983), 235-55; and C. Smith, “Hegel, Marx and the Calculus,” 256-70.

- ↩ Hubert C. Kennedy, “Karl Marx and the Foundations of Differential Calculus,” Historica Mathematica, 4, no. 3 (1977): 303-18. On receipt of some of Marx’s jottings, Engels replied: ‘The thing has taken such a hold of me that it not only goes round my head all day, but last week in a dream I gave a chap my shirt-buttons to differentiate, and he ran off with them.’ Engels to Marx, August 10, 1881, M-ECW, vol. 46 (New York: International Publishers, 1992), 131-2.

- ↩ Marx, Capital, II, chapters 20 and 21.

- ↩ Hegel, The Philosophy of History.

- ↩ Steven Nadler, “Malebranche on Causation,” Steven Nadler (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Malebranche (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 112-38.

- ↩ M-ECW, vol. 2 (London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1975), 275, 403-7, 472-3, 523 and 529-31.

- ↩ Karl Marx, “On the Jewish Question,” M-ECW, vol. 3, 150.

- ↩ Hegel, The Philosophy of History.

- ↩ Marx, Capital, III, 428 and 1007.

- ↩ Engels, “‘1885 Preface, Anti-Duhring,” M-ECW, vol. 24, 12n.

- ↩ G. F. W. Hegel, The Philosophy of Right [Law] (London: Encyclopedia Britannica, 1952), 2-3.

- ↩ Hegel, The Philosophy of Right, 6.

- ↩ Marx, “Thesis Eight,” M-ECW, vol, 5, 5 and 8; Mao Tse-tung, “Where do Correct Ideas come from?,” Four essays, 134-6

- ↩ S. Bradbury, “The Quality of the Image Produced by the Compound Microscope, 1700-1840,” S. Bradbury and G. L’E. Turner (eds), Historical Aspects of Microscopy (Cambridge: W. Heffer & Sons, 1967), 151-72.

- ↩ Engels, “Feuerbach,” 1970, 347; Simon Garfield, Mauve (New York: W.W. Norton, 2001).

- ↩ Engels, CCPE,

- ↩ ‘While, within a workshop, the iron law of proportionality subjects definite numbers of workers to definite functions, in the society outside the workshop, the play of chance and caprice results in a motley pattern of distribution of the producers and their means of production among the various branches of social labour.’ Marx, Capital, I: 476.

- ↩ For other examples, Marx, (CCPE, 100; Engels reviewing CCPE, 225; Frederick Engels, “Ludwig Feuerbach and the Outcome of Classical German Philosophy,” M–ECW, vol. 26 (London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1990), 371-2 and 383; Engels to W. Borgius, January 25, 1894, M-ECW, vol. 50 (London: Lawrence & Wishart, 2004) 265-7; Engels, “Supplement,” Capital, III, 1036.

- ↩ V. I. Lenin, “On the Significance of Militant Materialism,” Selected Works, vol. 3, 604.

- ↩ Pedestrian.

- ↩ A generous assessment would be that Popper had no access to any of Hegel’s writings while a refugee in New Zealand.

- ↩ His chapters on the Logic are too clear, subjecting Hegel to what Marx calls the crude English method in Darwin, Marx to Engels, December 11-12, 1859, M-ECW, vol. 40, 551.