On June 18 the government of Lithuania acted on a decision by the European Commission that goods and cargo subject to European Union sanctions could be prohibited from transiting between one part of Russia to another, so long as they passed through E.U. territory.

Almost immediately Lithuania moved to block Russia from shipping certain categories of goods and materials by rail to the Russian enclave of Kaliningrad, encompassing the former East Prussian Baltic port city of Konigsberg and its surrounding environs. They were absorbed into Russia proper as a form of war reparations at the end of the Second World War.

Lithuania cited its legal obligation as an E.U. member to enforce E.U. sanctions targeting Russia. Russia, citing a 2002 treaty with Lithuania which ostensibly prohibits such an action, has called the Lithuanian move a blockade and has threatened a military response.

A formation of NATO fighter jets flying over Lithuania in 2015. (NATO)

Lithuania, as a member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, or NATO, is afforded the collective security guarantees spelled out in Article 5 of the NATO Charter, which stipulate that an attack against one member is an attack against all. Through its actions, Lithuania risked bringing Russia and NATO to the brink of armed conflict, the consequences of which could be dire for the entire world given the respective nuclear arsenals of the two sides.

From the moment Russia initiated its so-called “Special Military Operation” in Ukraine, the nations that comprise NATO have been engaged in a delicate dance around the issue of how to support Ukraine and punish Russia without crossing the line of committing an overt act of war that could prompt Russia to respond militarily, thereby triggering a series of cause-effect actions that could lead to a general European conflict, and perhaps World War III.

In retrospect, the early debates in the European halls of power about whether to provide Ukraine with heavy weaponry seem almost innocent when compared to the massive infusion of weaponry that is taking place today.

Even Russia has softened its hardline stance going in, where it had threatened unimaginable consequences for any nation that interfered with its military operation in Ukraine.

Today the situation has evolved to the point where NATO is engaged in a de facto proxy conflict with Russia on Ukrainian soil which is designed, frankly speaking, to kill as many Russian soldiers as possible.

Russian Objectives

Russia, for its part, has adapted its posture into one that is designed to absorb these NATO-linked blows while pursuing its stated military and political objectives in Ukraine with a single-minded purpose.

Ukraine has used NATO-provided weapons and NATO-provided intelligence to lethal effect on the battlefield, killing several Russian generals, sinking the flagship of the Russian Black Sea Fleet and killing and wounding thousands of Russian soldiers while destroying hundreds, if not thousands, of vehicles and pieces of military equipment.

The relative restraint of the Russian approach is evident when contrasted with the hysteria of the United States during its two wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Qassem Suleimani, an Iranian general who oversaw an Iraqi resistance against the U.S. occupation of Iraq in the mid-2000’s that was purportedly responsible for the deaths of hundreds of U.S. servicemen, was assassinated by the U.S. government more than a decade after his alleged activities. And it was only a year ago that the U.S. media was in an uproar over allegations (subsequently proven false) that Russia was offering bounties to the Taliban to kill U.S. soldiers stationed in Afghanistan.

The latter claim best illustrates the hypocrisy of the U.S. today. The “bounty” claim was premised on a single attack that left three U.S. servicemen dead. The U.S. today openly brags about killing hundreds of Russians in Ukraine.

Red Lines

Russia’s red lines in Ukraine have evolved to encompass two basic principles–no direct military intervention by NATO forces on Ukrainian soil/airspace and no attack against Russia proper.

Even here, Russia has displayed great patience, tolerating the presence of U.S. special operations forces in Ukraine and holding back when Ukrainian forces, most likely supported by NATO-provided intelligence, engage in limited attacks on targets inside Russia.

Rather than respond by attacking the “decision making centers” outside Ukraine responsible for supporting these actions, Russia has engaged in a graduated campaign of escalation inside Ukraine, striking the very weapons being delivered under the oversight of U.S. commandos and the Ukrainian forces who use them.

It is in this context that the Lithuanian decision to impose a rail blockade on Russia seems to be a stark departure from current NATO and E.U. policy.

Russia immediately made its ire known, indicating that it viewed the Lithuanian actions as an overt act of war which, if not reversed, would result in “practical” measures outside the realm of diplomacy to rectify the situation.

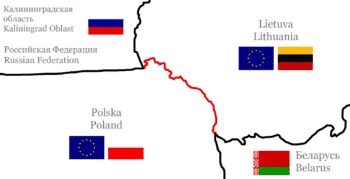

Close-up at the Suwalki Gap. (Photo: Jakub Luczak, Wikimedia Commons)

The rhetoric was ratcheted up to high, however, when Andrey Klimov, a Russian senator who chairs the Commission for the Defense of State Sovereignty, called the Lithuanian action “an act of aggression” which would result in Russia seeking to “solve the problem of the Kaliningrad transit created by Lithuania by ANY means chosen by us.”

The Suwalki Gap

For years, NATO has worried about the possibility of a war with Russia in the Baltics. Much of NATO’s attention has been focused on defending the “Suwalki Gap,” a 60-mile-long stretch of border between Poland and Lithuania that separates Belarus from Kaliningrad. Western military experts have long speculated that, in the event of any conflict between Russia and NATO, Russian forces would seek to advance on the Suwalki Gap, joining Kaliningrad with Belarus and severing the three Baltic nations from the rest of Europe.

But while NATO has focused on defending the Sulwaki Gap, a Russian lawmaker has suggested that any Russian military attack in the Baltics would avoid involving Belarus. Instead, it would focus on securing a land bridge between Kaliningrad and Russia by driving north, along the Baltic coastline, to Saint Petersburg.

A series of wargames conducted by RAND around 2014 showed that NATO was, at the time, not able to adequately defend the Baltics from a concerted Russian attack. According to the wargame results, Russian forces were able to overrun the Baltics in about 60 hours.

Similar projections of Russian offensive prowess against Ukraine–where some military officials, including U.S. chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Mark Miley, predicted that Russian forces would take Kiev within 72 hours–proved wrong. But the reality is that the militaries of the three Baltic nations are not on par with those of Ukraine, either in quality or quantity, and there is little doubt Russia, even distracted in Ukraine, could deliver a fatal blow to the militaries of the three Baltic nations.

Escalating Rhetoric

The rhetoric out of Russia continues to escalate. Vladimir Dzhabarov, a deputy head of the Foreign Affairs Committee in the lower house of Russia’s Parliament, has threatened that any continued blockade of Kaliningrad “could lead to an armed conflict,” noting that “the Russian state must protect its territory and ensure its security. If we see that a threat to our security that is fraught with a loss of territory, we will certainly take extreme measures, and nothing will stop us.”

If there is one take away from the Russian military operation in Ukraine, it is that Russia doesn’t bluff. NATO and the rest of Europe can rest assured that unless a solution is found that brings an end to Lithuania’s blockade of Kaliningrad, there will be a war between NATO and Russia.

With this reality in mind, the E.U. is working on a compromise arrangement with Lithuania that seeks to have the Russian rail connection with Kaliningrad returned to normal in the near future. This deal, however, must work to Russia’s satisfaction, an outcome which is yet uncertain.

Unlike the Ukrainian conflict, a war in the Baltics will have existential aspects for both sides which brings the possibility–indeed probability–of nuclear weapons being used. This is an outcome that benefits no one and threatens everyone.

Scott Ritter is a former U.S. Marine Corps intelligence officer who served in the former Soviet Union implementing arms control treaties, in the Persian Gulf during Operation Desert Storm and in Iraq overseeing the disarmament of WMD. His most recent book is Disarmament in the Time of Perestroika, published by Clarity Press.