In wars like the present one, politics on the home front cannot be permitted to give aid and comfort to the enemy. In the U.S. and NATO campaign, the Russian oligarchs and their businesses are targets and also weapons of the plan for regime change in the Kremlin. What role they will play personally in the future of the Russian war economy, and how their assets, cashflows, profits and investments will be managed, are bound to be closely held secrets.

Original interview and RBC report in Russian.

So when the aluminium oligarch Oleg Deripaska (lead images, left left, right left) and the nickel oligarch Vladimir Potanin (left right, right left) appeared to agree to announce publicly on July 4 that they are negotiating a merger of their companies Rusal and Norilsk Nickel (Nornickel) into a single national mining and metals champion, they may be telling the truth; or they may be running a disinformation operation against each other; or they may be flying a trial balloon over the Kremlin to see what President Vladimir Putin will decide.

Potanin spoke first; he has detested Deripaska in the past. For the time being Deripaska has said nothing. The spokesmen for their companies are saying nothing on the record.

Potanin may have intended to sandbag Deripaska before the latter expected it. Last Monday they both knew that what Potanin said would immediately boost Rusal’s share price and damage Norilsk Nickel’s, and that is what happened, making the merger proposal appear to be Deripaska’s initiative, not Potanin’s.

The last three times Deripaska tried a hostile takeover against Potanin–in 2008, 2010, and 2015–Putin refused to allow it. That the president is the one to decide again is too obvious to be a state secret now. That the Rusal-Nornickel merger is a much greater test of the war economy plan than the Central Bank’s rouble and interest rate policies, or the government’s capital export controls is also no secret. Whether Putin has made up his mind this time, and what he will decide remain secret. So is the fight to persuade him to say yes or no.

These wartime stakes and the secrecy also mean that for the first time in the twenty-six years of Russian oligarch history, nothing published in the western press can be true–least of all, the New York propaganda agencies Reuters, Bloomberg, and Wall Street Journal, and the Japanese mouth organ in London, Financial Times.

To follow the history of the Deripaska raids, click to read the 2008 chapter here and here. For the Putin’s nyet in 2010, click again. And for Deripaska’s Mrs Potanin divorce ploy of 2015, read this.

On July 4, Potanin revealed in a videotaped interview with Moscow business medium RBC he is likely to have paid for: “we have received a proposal from the management of Rusal to discuss the merger with Norilsk Nickel as an alternative to extending the shareholder agreement [expiring at the end of 2022]…I sent a letter in which I confirmed our agreement to start the process of discussing a merger with Rusal.” He also said the deal would create “a national champion”.

The full text of what Potanin told RBC has not been quoted in the western press. “I believe”, Potanin said after discussing several other topics,

it is time to move to normal corporate governance from 2023, which we plan to move to. I think it will be in the interests of all the shareholders. As for the dialogue with UC Rusal, then, you know, again, as they say, it’s a long story [лыко в строку]. I have already said that the erosion of strong management in our country is a negative trend that we must fight against. And it is widely known that with Oleg Deripaska we have different approaches to business processes. But he is a strong leader. And in 2018, when he resigned from the leadership of UC Rusal, it weakened UC Rusal. And I see this just by my own concrete experience. There was no one there to talk to after he left. And the consequence, albeit complicated and difficult to perceive–but there it was. And now he’s gone. And this began to be expressed in the fact that UC Rusal began to allow itself such things that, let’s say, the company did not allow itself under the founder: refusal of certain obligations, a certain inconsistency, and so on. And this once again makes me say that we must fight so that we have strong people who are able to lead teams, so that they are not diluted out of management. And this is also one of the reasons why cooperation with UC Rusal under the previous agreement potentially carries risks and could potentially harm Norilsk Nickel and all its shareholders.

But the latest offer we have received from the new management of UC Rusal is to discuss a merger between Norilsk Nickel and UC Rusal as an alternative to extending the [shareholders] agreement [of December 2012-December 2022 ]. We have reconsidered [the idea of merger]. And I have today (the interview was conducted on July 4–RBC) sent a letter confirming our consent to start the process of discussing a merger with UC Rusal. Because it allows you to create a national champion. This makes it possible to further diversify the shareholder base. And if earlier the same ideas had been floating about for a long time, about the potential merger of UC Rusal and Norilsk Nickel, in a sense, UC Rusal does not say so directly, but the acquisition of 25% of one large industrial company in another is always a step towards a merger (meaning the buyout in 2007 by the company when Russian Aluminium bought 25% plus one share of Norilsk Nickel from Mikhail Prokhorov’s holding– RBC). Because there are different kinds of mergers–friendly or unfriendly, acquisitions or non-acquisitions. But when one large industrial company buys a large stake in another industrial company, it is usually an invitation to merge. We have always had a negative attitude towards such mergers, because we have not seen and still do not see any production synergies. That is, we have different competitive advantages. Therefore, we have not seen any production synergy between them.

But now other factors have appeared; because of them I am ready to discuss the merger of UC Rusal and Norilsk Nickel. This includes sustainability, this is the so-called green agenda. UC Rusal is the company which produces the most ‘green’ aluminium compared to all other companies. Norilsk Nickel is also making great efforts in this direction and produces nickel and palladium for batteries for the future green economy, too. Plus, there is a need to diversify the shareholders’ composition, and to build up additional resistance to sanctions; and if required, to receive state support for the companies’ projects in Russia. All this made us return to this UC Rusal proposal.

On July 6, Putin’s spokesman Dmitry Peskov responded that the merger is “a corporate matter”. If Peskov had said nothing at all, the meaning would be the same; that’s to say, the opposite of the words which came out of his mouth.

This is only the most recent of see-through Caprtveils which have been tried before. In 2011, Putin and Igor Sechin, then deputy in Putin’s prime ministry, announced: “Deputy Prime Minister Igor Sechin, who supervises the resource concessions and controls the oligarchs, answered questions from the Wall Street Journal about the oligarch conflict on the Norilsk Nickel board by saying: ‘The government does not intervene in corporate practices….The shareholders should take the appropriate decisions, most importantly that they [should be] civilized, in the framework of the existing legislation.’ That veil meant Putin was in favour of preserving the status quo – it also meant no to Deripaska.

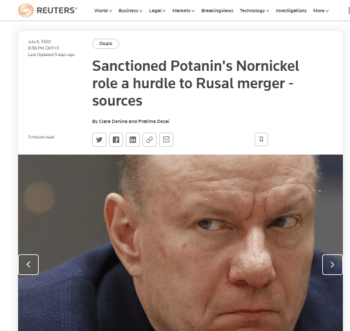

Source: https://www.reuters.com/

Last Wednesday, July 6, Reuters reported “two sources with direct knowledge of the matter” as claiming “a merger will not happen while Potanin remains boss of and a major shareholder in Nornickel.”

Of the two bylined reporters, Clara Denina is English and employed by Reuters in London to report on mining; the second reporter Pratima Desai, also based at the Reuters bureau in London, covers metals. Neither of them has any Russian business experience. The three editors who worked on the piece have never worked in Moscow; their links are to Anglo-American banks and companies and PR agents in the London market. To illustrate their report, the editors retrieved the most hostile Potanin close-up they could find in their files; this one dated from December 12, 2017. The available evidence suggests the likelihood that Deripaska authorized the placement of his reaction through go-betweens. If they took payment, they were violating the current U.S. and EU sanctions.

The two Reuters reporters and three editors identified in the publication knew they were concealing that their sources were linked to Rusal; the response they report confirms that Deripaska had moved first in private, and that Potanin had decided to pre-empt and go public. “‘Until he bites the bullet, steps down as CEO and sells down his stake to become a minority shareholder, no deal is possible,’” Reuters claimed one of the anonymous direct-knowledge sources added, signaling that Deripaska remains as personally hostile to Potanin as ever. Reuters then added fresh Deripaska rancor. “A third source with direct knowledge of the matter said they were unaware of any talks taking place and that Potanin’s interview comments represented posturing ahead of negotiations to replace a dividend payment agreement due to expire this year. ‘This is a manoeuvre. It is not a proposal of a deal,’ a fourth source said.”

Reuters omitted to report that Potanin is proposing to cut the cash dividend Nornickel will pay to Rusal; this cash-conservation measure has been calculated by Moscow analysts as reducing the payout to roughly one-third of its pre-war 2021 level; the formula is being adopted by most major Russian metals companies in the war conditions. However, Deripaska and the sources he authorized to speak to Reuters want to prevent Potanin’s cut and keep Nornickel’s profits flowing through Rusal into Deripaska’s pocket.

The Reuters innuendo is Deripaska’s, blaming Potanin for the move Deripaska initiated himself for a motive he is trying to disguise until he is confident he has Putin’s support. For the time being, no Russian will say so.

Kirill Chuiko

The only Russian analyst to talk to a western publication by name told Bloomberg he doubted the likelihood of the merger. “Despite Potanin’s latest comments, the merger still seems unlikely, according to Kirill Chuiko (right), an analyst at BCS Global Markets. ‘The national champion idea may be seen as an additional guarantee against the sanctions, but still it is not possible to be fully safeguarded this way,’ he said. ‘The parties have long and extremely difficult history of relations, while businesswise the merger still makes no sense.’” No reporter for this story has been identified.

Finam, a Moscow asset manager and brokerage, has published a conventional analysis of the balance-sheets of the two companies, with calculations of the impact of the merger on their revenues, earnings, dividends, debt, and share prices. The Finam report cites no anonymous sources from either camp; publishes no innuendoes; takes no sides; and says nothing about the politics of the deal.

“We believe”, wrote Danilov,

Finam analyst Vasily Danilov composed the report. (Photo: Finam)

that Rusal’s stake in Norilsk Nickel (26.2%) can be distributed among Rusal’s current shareholders (0.2655 shares of Norilsk Nickel per 100 shares of Rusal). Rusal’s shareholders will also receive a certain number of Norilsk Nickel securities issued by the company specifically for takeover purposes. It is also possible to assume the takeover of Norilsk Nickel by Rusal (that Rusal already has 26.2% of Norilsk Nickel hints at such a possibility), however, we believe this option is less likely….

The consolidation of the business will lead to an increase in its importance for individual regions and the country as a whole, as a result of which the authorities will listen more sensitively to the opinion of the company and be more willing to provide support, including in the field of key investment projects. In our opinion, the main benefit directly for Vladimir Potanin may be the dilution of the shares of the current shareholders of Norilsk Nickel, as a result of which the En+ package (indirectly owning Norilsk Nickel through 56.9% of Rusal) may fall below the blocking 25%, but this will depend on the parameters of the merger. Vladimir Potanin’s share (35.6% of Norilsk Nickel) in the combined company will also be smaller, but it will still remain blocking and may become the sole blocking stake. At the same time, the advantages of the merger are not so obvious for the minority shareholders of Norilsk Nickel. The combined company will become larger in revenue, but profitability will suffer. According to our calculations, Norilsk Nickel’s EBITDA [earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortization] margin in 2022 should be 61% versus 42% in the case of a merger with Rusal. Also, despite the increase in the scale of the business, the current shares of Norilsk Nickel shareholders will be blurred….

With the current debt load, Norilsk Nickel distributes 60% of EBITDA [earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortization] to dividends. The company’s management and Interros [Potanin’s holding] have repeatedly talked about the need to link payments to free cash flow, which, on the one hand, will lead to a decrease in the volume of dividends, but on the other hand will avoid increasing the debt burden. A moderate debt burden allows the company to pay 75% of FCFF [free cash flow] to shareholders. According to our calculations, in this case the total dividend for 2022 will be $20.3 per share (1,285 rubles. per share at the current exchange rate with a yield of 7.8%). However, there is a risk that in the new [Potanin] version of the dividend policy, the payout ratio will be fixed at 50% FCFF (as was done with payments for 2020), as a result of which the dividend for 2022 will decrease to $13.6 per share (857 rubles. per share with a yield of 5.2%). In both scenarios, the sum of the [dividend] payments will be significantly lower than the level of 2021 ($36.5 per share)–that is what Vladimir Potanin is proposing. Too, there is uncertainty about the dividend policy in the event of a merger between Norilsk Nickel and Rusal. However, we believe that it will also be tied to free cash flow.

SHARE PRICE TRAJECTORY OF RUSAL AND NORNICKEL, YEAR TO DATE

Key: black=Nornickel; yellow=Rusal. Source: https://markets.ft.com/

Nornickel’s current market capitalization is Rb2.6 trillion; Rusal’s market cap is Rb839.5 billion.

The Finam report is written as if there is no war, and as if there is consensus in Moscow over how to manage the war economy plans of the major corporations. In this debate there is no mentioning the president by name. Codewords are used instead–for Putin’s decision-making over whether rouble and bank interest rates should be set high or low, and capital controls fixed tightly or loosely, the codeword is Nabiullina, the name of the Central Bank governor reappointed by Putin on March 18; follow that policy debate here. For the bitter contest over mobilization of resources, labour and investment between nationalization, central planning and state socialism on the one hand, and the oligarch capitalism of the past twenty-two years on the other hand, read this.

In public the oligarchs also use codewords.

On July 6, the state news agency Tass reported Potanin backing the special military operation and Russia’s endurance against the U.S. sanctions war.

Westerners are screaming even louder than we are. Their pain threshold is lower than ours, they are not used to inconveniences and discomfort. In this sense, they are not competitors to us. We can stand it longer than they. I am one hundred percent sure of it. In situations of standoff the winner is the one who is ready to endure pain longer — who has a stronger and trusted leader. The mandate of our president is more powerful than the mandate of any politician in the West. For this reason, I look into the future with cautious optimism. We have time and we know how to be patient, while among our opponents we observe mainly loud shouting and groundless hopes that we will break down under the pressure of sanctions. This is definitely not going to happen.

On his Telegram channel, Deripaska has been repeatedly critical of the objectives of the special military operation. In his latest Telegram post on July 6, Deripaska declared himself in favour of “recogniz[ing] that the future sustainable development of Russia is possible only on the basis of a private, market, competitive and open economy. It is necessary to release from custody all the accused under economic articles [of the Criminal Code], with authorization of bail. Amend articles 159 and 160 [fraud] so that suspicions of economic crimes do not lead to senseless holding of entrepreneurs as hostages…Decriminalization of the business sphere solves several important tasks at once: it expands freedoms and prevents unfair competition, and as a result it will return billions of euros withdrawn from circulation back to the Russian Federation. Only in such conditions should we count on the growth of entrepreneurial activity, which will bring with it the stabilization of the Russian economy, increased investment, an increase in the number of new jobs (because many old ones will not be saved), an increase in labour productivity, and much more. There is a similar story with state capitalism. We need to forget about it, as about collective farms, unless this mould will have completely rotted Russia. Its dominance provokes stagnation, preventing entire industries from truly developing, hindering competition and increasing costs for everyone. State capitalism is a senseless dead-end path of development, which must be completely forgotten during this crucial period in the history of our country.” For more background on the oligarchs’ policy plans, read this.

On July 6, the state news agency Tass reported Potanin backing the special military operation and Russia’s endurance against the U.S. sanctions war.

Last week, when Deripaska proposed his merger and Potanin responded, they made public for the first time that they are asking Putin to decide whether the stringencies of war require his choosing between the oligarchy he has directed for the past 22 years, or nationalization of their assets and profits.

Before that decision, each of the investment bank analysts listed (approved) by Rusal and Nornickel as experts on the two companies was asked how they interpret the merger proposal. There are seventeen for Rusal; nine for Nornickel; five overlap, covering both companies. They were asked: 1. Do they interpret the proposed merger as intended to stop nationalization? 2. Do they interpret Potanin’s announcement as a manoeuvre, according to the Reuters report, and not a genuine deal negotiation? 3. Do they agree that the Kremlin must approve such a transaction creating a national champion?

The responses requested by telephone and email over two days produced either a point-blank refusal to answer or the evasion of requesting an email and then not replying. No analyst refusing to answer the questions would give a reason except for the analyst at Alphavalue in Paris–“we provide comprehensive, unconflicted research-only” — who said his firm replies only to questions asked by Reuters, Bloomberg or the Financial Times; and then only on condition the name of the firm is advertised.

Source: https://www.rferl.org/

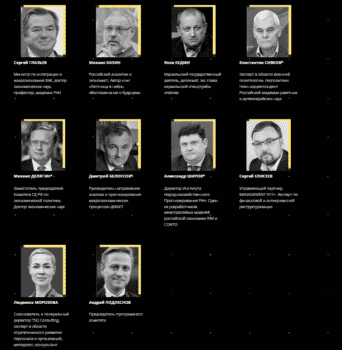

The two leading domestic advocates for removing Nabiullina and changing Central Bank policy, as well as for nationalization and central planning of the war economy, are Sergei Glazyev, a former Kremlin economic policy adviser and currently the Kremlin appointee as minister for integration and macroeconomics of the Eurasian Economic Commission (EEC, aka EAEU ), the bloc of former Soviet states coordinating customs, central banking, trade and fiscal management policies; and Mikhail Delyagin, a parliamentary deputy and chairman of the State Duma Committee on Economic Policy. Together, they are members of the Anti-crisis Expert Council. The ten members of the council are listed here.

Writing on his blog on July 6, here is Delyagin’s commentary in full:

A mega-concern is to be created in Russia capable of dictating its will to the state. The plans for the merger of Norilsk Nickel and Rusal look very suspicious; the two oligarchs seem to be up to something unkind, anti-Russian. The alliance does not promise any economic benefits, the companies are too different. However, the billionaires are attracted to each other. The response to such a threat should be the prompt nationalization of both oligarchic structures, which have been causing great harm to Russia for many years.

Norilsk Nickel still does not see any production synergies with UC Rusal. However, the merger of the two companies will create a ‘national champion’. It will be easier for the unified company to receive state support for projects in Russia, if need be, says Vladimir Potanin, the president and largest shareholder of Norilsk Nickel. Translating that into Russian–the huge company will be able to dictate its conditions to the authorities, and they will be forced to follow the lead of its owners. Potanin himself has a reputation as a ‘silent man’; he seems to be friends with the Kremlin and is always ready for a dialogue with the authorities. But this is nothing more than a mask, a comfortable spot to occupy, in some ways even a prudent one. However, what lies behind it, we do not know. Nothing good, that’s for sure. On the contrary, the owner of Rusal is in the outspoken opposition. ‘The iron curtain has already come down. I am being asked not to say this, but I am for peace,’ Oleg Deripaska said shortly after the start of the special operation.

‘The Iron Curtain’ is, of course, good, or it’s bad, depending on how you view it. But you need to know the history, otherwise such statements will look stupid. If you look at our recent history, then it was not us who lowered this precise ‘curtain’ during the Soviet years. And now it’s exactly the same situation. Russia seems to be open, but they don’t let us go abroad, they don’t want to trade with us or communicate with us in general.

Nevertheless, the position of the billionaire [Deripaska] is quite understandable–he is clearly on the side of the West and, as you might guess, he considers the Russian Federation nothing more than a ‘cash cow’. Pump out more funds, withdraw them anywhere–and then [leaving in Russia] nothing more. However, Norilsk Nickel has exactly the same policy–don’t give a damn about anything, both the people and the environment. The recent monumental ecological disaster at Norilsk is a clear confirmation of this.

Most of the products of both concerns are exported; the Russian market is basically not interesting enough for the oligarchs. At the same time, imported aluminium profiles and other aluminium supplies from foreign manufacturers are in the stores. Because the sale prices for the Russian Federation are simply prohibitive! Considering that Rusal is the largest manufacturer of this special metal, I consider this pure sabotage.

However, in the event of the emergence of a mega-concern, everything will become even worse. Under the threat of unrest likely to be caused by the possibility of closing factories (all over the country!), the rich will begin to twist the arms of the authorities. For those who can’t be bought. More precisely, it won’t be exactly this way–almost everyone will be bought, and the few who are not for sale will be intimidated by the threat of ‘growth of social tension’. And that’s it, finished! [хана]–do whatever you want.

Members of the Anti-crisis Expert Council.

There can be only one answer to such a threat–nationalization. And it should be comprehensive. Start, yes, with these two corporations, but do not stop there… the metallurgy sector, both non-ferrous and ferrous; the oil and gas sector; the coal industry; energy, mechanical engineering (or more precisely, what’s left of it), the military-industrial complex, the aviation industry, the chemical industry, and so on. If all Russian manufacturing companies begin to receive the products of these industries at cost, this will be an excellent tool for a powerful economic breakthrough.

Undoubtedly, this control is needed. The skeptics have repeatedly said that the officials themselves, primarily the minister-level ones, can become the new oligarchs. Yes, they can be that in many ways already now, hiding away from all the issues being decided by some rich Ivan Ivanych. Often he remains only the screen behind which the ‘special princeling’ rules–the governor or the city mayor. Accordingly, not any kind of central control is necessary, but PEOPLE’S control is required…And Gosplan, yes, it is necessary to revive it, together with the Soviet system of sectoral ministries, because what exists now is in no position to manage anything effectively. This has been discussed more than once–for example, last summer when the chairman of the Just Russia-For Truth party, Sergei Mironov, proposed reviving the Ministry of Geology… Russia does not need the current Ministry of Industry and Trade, which is not responsible for anything. But ministries of ferrous and non-ferrous metallurgy, for instance, are very much needed. Moreover, due to modern means of communication, collection and processing of information, their staff can be kept to a minimum, and there is no need to set up analogues of the Soviet structures (which, by the way, were quite effective). Applications from enterprises come to the order bureau of the ministry, for example, for a particular range of rolled products, with addresses for the recipients and other details. And an electronic system would then allocate them among the manufacturing plants. This means confiscating [steel oligarchs] Mordashov [Severstal], Abramovich [Evraz], Lisin [NLMK], Rashnikov [MMK], and others like them. The model, of course, is extremely simplified, but in general it is something like this.

Undoubtedly, there will be glitches, and the intervention of both ministerial figures and people’s controllers will be required. But such a system of resource distribution can be brought to optimization very quickly. Stable low prices, the absence of speculation and all kinds of man-made ‘crises’, confidence in the future. This is what is needed for the economic development of the country. What remains is only to make the decisions and get down to business.