The British Parliament is debating a national security bill which could undermine the basis of national security reporting and ultimately throw journalists in jail for life.

A person convicted under the new offense of “obtaining or disclosing protected information,” defined in Section 1 of National Security Bill 2022, faces a fine, life imprisonment, or both, if convicted following a jury trial.

A review of the parliamentary debate on the bill makes clear that work by press outlets such as WikiLeaks is at the heart of Tory and Labour MPs’ thinking as they push to make the bill law.

As currently written, direct-action protests, such as those conducted by Palestine Action against U.K.-based Israeli weapons manufacturer Elbit Systems Ltd, could also be captured under the offences of “sabotage” and entering “prohibited places” sections of the bill.

Whistleblowers, journalists and publishers focusing on national security related matters may be most at risk of being prosecuted, though any person who “copies,” “retains,” “discloses,” “distributes” or “provides access to” so called protected information could be prosecuted.

“Protected information” is defined as any “restricted material” and it need not even be classified.

Under this bill, leakers, whistleblowers, journalists or everyday members of the public, face a potential life sentence if they receive or share “protected information” which is widely defined.

That does not mean imprisonment from one day “up to” a life sentence. If a judge determines a fine isn’t suitable enough punishment the only alternative is life in prison. Following a conviction, a judge would have no choice but to either issue a fine or hand down a life sentence, or both.

[Read the bill in its entirety here.]

There is no public interest or journalistic defense in the bill, a fact noted by some of the parliamentarians during the debates.

“The glaring omission at the heart of the National Security Bill is a straightforward public-interest defense, so that those who expose wrongdoing, either as whistleblowers or journalists, will be protected,” Tim Dawson, a long-time member of the National Union of Journalists’ National Executive Council told Consortium News.

“Without this, there is a risk of concerned U.K. citizens being prosecuted as though they were foreign spies,” he added.

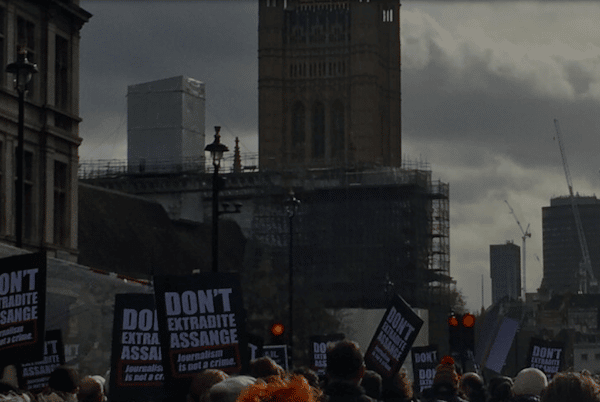

The bill can be seen as part of a growing crackdown in both Britain and the United States against legitimate journalism that challenges establishment narratives.

In many respects, the proposed law, which applies to people both inside and outside the U.K., shares many elements with the draconian 1917 Espionage Act, which the U.S. government is using to prosecute WikiLeaks publisher Julian Assange.

Assange is charged with 17 offenses under the Espionage Act, amounting to a maximum 170 years in prison. None of the charges allege conspiring with a foreign power and merely pertain to receiving and publishing documents leaked to him by U.S. Army whistleblower Chelsea Manning.

No Evidence of Harm

As is the case with the U.S.’ Espionage Act, no evidence of actual harm needs to be proven by prosecutors in order to secure a conviction under the National Security Bill.

There is a broad test of whether the defendant knows or “ought reasonably to know” that their conduct is “prejudicial to safety or interests of the U.K.”

What is, or is not, “prejudicial” to the “safety” or “interests” of the U.K. is also to be determined by the government of the day, according to long established case law from the U.K.’s highest court.

This could include anything from environmental, energy, climate and housing policy, to policing, foreign affairs or military policy.

WikiLeaks-Style Publications

A review of the parliamentary debates over the bill shows that although it is being justified on the basis of protecting the U.K. from the “serious threat from state-backed attacks on assets, including sites, data and infrastructure critical to the U.K.’s safety or interests,” national security leaks and reporting–including that of WikiLeaks — is explicitly in the minds of at least some of the key politicians supporting the bill.

“Will the right honourable lady condemn the WikiLeaks-type mass dumping of information in the public domain? It is hugely irresponsible and can put lives at risk,” Tory MP Theresa Villiers asked Labour’s Shadow Home Secretary Yevette Cooper, on June 6.

“Yes, I strongly do, because some of the examples of such leaks that we have seen put agents’ lives at risk, put vital parts of our national security and intelligence infrastructure at risk and are highly irresponsible,” Cooper replied, adding,

We need safeguards to protect against that kind of damaging impact on our national security.

There is no evidence that anything published by WikiLeaks has resulted in the loss of life.

A U.S.-leaked government report itself concluded that there was “no significant ‘strategic impact’ to the release of the [Iraq War Logs and Afghanistan War Diary]”, from the Manning leaks which Assange is being prosecuted over. “No actual harm [against an individual]” could be shown either, a lawyer acting for the U.S. government admitted during Assange’s extradition hearings.

This contradicts the official government line that the leaks caused serious harm.

Broad Threat

Among the many disclosures revealed by WikiLeaks, include the secret texts of proposed corporate and investor rights treaties such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

These treaties, which were being negotiated in secret and would not have been known to the citizens until just before or even after they had become law, would have preferenced corporate rights over domestic laws and subordinated labor, environmental and health protections and climate policy to the profit-making imperatives of private industry. Their passage stalled after their draft texts were leaked and then published by WikiLeaks.

WikiLeaks revelations also include dramatic incidents such as the execution of 10 handcuffed Iraqi civilians in their family home, including four women, two children and three infants, by U.S. soldiers who later ordered an airstrike to cover it up.

Many around the world might still believe that a U.K. plan to build the world’s largest “marine park” in the Chagos Islands was motivated by environmental concerns, were it not for a cable published by WikiLeaks revealing that the true purpose was to prevent the indigenous population from ever being able to return to their land.

Torture and rendition of civilians as well as other war crimes were also revealed by WikiLeaks.

All such material, which are among the documents Assange is being prosecuted by the U.S. for publishing, would fall under the National Security Bill’s definition of “protected information.”

Conspiracy with Foreign Power

In theory, involvement of a “foreign power” must also be proven for Section 1 of the bill to apply. But a review of the “foreign power condition” in Section 24 of the bill shows a myriad of ways that this condition could be satisfied.

Section 24 reads as follows:

24 The foreign power condition

(1) For the purposes of this Part the foreign power condition is met in relation to a person’s conduct if —

(a) the conduct in question, or a course of conduct of which it forms part, is carried out for or on behalf of a foreign power,

and

(b) the person knows, or ought reasonably to know, that to be the case.

(2) The conduct in question, or a course of conduct of which it forms part, is in particular to be treated as carried out for or on behalf of a foreign power if —

(a) it is instigated by a foreign power,

(b) is under the direction or control of a foreign power,

(c) it is carried out with the financial or other assistance of a foreign power, or

(d) it is carried out in collaboration with, or with the agreement of, a foreign power.

(3) Subsections (1)(a) and (2) may be satisfied by a direct or indirect relationship between the conduct, or the course of conduct, and the foreign power (for example, there may be an indirect relationship through one or more companies).

(4) A person’s conduct may form part of a course of conduct engaged in by the person alone, or by the person and one or more other persons.

(5) The foreign power condition is also met in relation to a person’s conduct if the person intends the conduct in question to benefit a foreign power.

(6) For the purposes of subsection (5) it is not necessary to identify a particular foreign power.

(7) The foreign power condition may be met in relation to the conduct of a person who holds office in or under, or is an employee or other member of staff of, a foreign power, as it may be met in relation to the conduct of any otherperson.

Foreign Funded Organizations

The foreign power condition could potentially be satisfied, therefore, due simply to the involvement, at any stage, of a journalist working for news outlets such as Al Jazeera, Press TV, CGTN, RT, Voice of America, France 24, Redfish or TeleSUR.

Tory MP David Davies, himself a supporter of the bill despite being known for his criticism of the prosecution of Assange, noted that “[human rights group] Reprieve, Privacy International, Transparency International and other excellent organizations that do very good work have received some funding from other nations’ Governments” and could therefore “fall foul” of this law.

“Perfectly legitimate organizations could be left committing an offence, under this area of the bill, if they use leaked information–which may not even be classified–to challenge government policy,” Davies added.

Furthermore, what is deemed to be a “perfectly legitimate organization” is in the eye of the beholder and can change over time–as proven by the increased E.U. and U.S. censorship of RT and Sputnik since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Even if a foreign power is proven to somehow be involved, either in the obtaining of restricted material, sharing or publishing it, there is no apparent need to prove conspiring with that foreign power for the condition to be satisfied and therefore for a defendant to be convicted.

Therefore, if a person reports upon U.K. government documents–which prosecutors argue have been hacked and released by a foreign government agency, or even a hacker group infiltrated or influenced somehow by a foreign government agency–they could be found guilty under this law, without any evidence either of participation in the hack or conspiracy with a foreign power.

The Bill and the Official Secrets Act

Following the revelations of mass, warrantless, government surveillance, by NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden, as well as WikiLeaks revelations of war crimes and other state wrongdoing, the Cabinet Office asked the Law Commission to review its official secrecy, data protection and espionage laws.

In 2020, the Law Commission recommended replacing the Official Secrets Acts 1911, 1920 and 1939 with an Espionage Act, and updating the Official Secrets Act 1989. Many of its recommendations on ‘reforming’ U.K, secrecy laws, would make it easier to bring prosecutions against whistleblowers, journalists and publishers by lowering so called “barriers to prosecution”.

For example, the Law Commission recommended that prosecutors should no longer have to prove that leaks by public servants and contractors, covered by the 1989 Act, have caused “damage”. The 1989 Act is the main legislation currently used to target whistleblowers, leakers, journalists and publishers.

The National Security Bill repeals the older official secrets laws and expands criminalisation of conduct which might be useful to an “enemy” with the more broadly defined “foreign power”. This bill also adopts recommendations to expand what can be labelled a “prohibited place” beyond military sites. Section 1 applies to people based outside the U.K,, regardless of their nationality, and this appears to flow from the Law Commission’s proposed amendments to the 1989 Act, which currently only applies to U.K. citizens.

Technically, the National Security Bill hardly amends the Official Secrets Act 1989. Perhaps this is because the Home Office opposes the Law Commission’s insistence that revisions to the 1989 Act re-introduce a public interest defence, which could be used by journalists and everyday civilians. The Home Office also opposes the idea of an independent body to receive whistleblower concerns. Yet many of the most draconian recommendations have been implemented in some form in the Bill.

Section 1 of the Bill–which lacks any requirement to prove damage along with the overly broad foreign power condition– could simply be the Home Office’s way of seeking to expand the scope of conduct covered by the 1989 Act as much as possible without explicitly doing so. The National Security Bill therefore appears to fall foul of the Law Commission’s recommendations that the definition of a foreign power “should not render the offense overly broad”.

National Security Reporting

In 2018, emails and other documents belonging to the Institute for Statecraft’s Integrity Initiative, a now defunct U.K.-based, intelligence services-linked, propaganda and psyop organization, were hacked and published online.

The documents revealed that the Integrity Initiative was receiving funding from the U.K. Foreign Office, Facebook, NATO and neoconservative-linked foundations, and was engaged in directing anti-Russian, anti-left and pro-NATO propaganda towards the European and U.K. public.

Integrity Initiative documents, including emails and a contract with the U.K. Foreign Office, revealed an ambitious global agenda involving secret “clusters” of academics, journalists, policy makers and national security-linked officials in Europe, North Africa and North America, with more being planned.

The hacked documents revealed that the purpose of the Integrity Initiative was to shape public opinion and public policy under the guise of combatting Russian “disinformation.”

A group called Anonymous Europe claimed responsibility, though the Foreign Office and Western media suggested, without evidence, that the Russian government was somehow behind the hack.

The BBC even reported, also without evidence, that the documents were “leaked to the Russian media.”

In fact, the documents were published on an internet messaging board and available to anyone aware of the website, including independent British and American journalists who reported upon them.

Reporting on such documents, if the National Security Bill becomes law, could be considered a violation of Section 1, given that some of the files were “restricted” government documents and the Integrity Initiative was partially government funded. If foreign government actors were involved in hacking or releasing the documents that alone could satisfy the “foreign power condition” in Section 24.

Even the fact that journalists (including British citizens) who were writing for foreign government-funded news outlets reported on the documents could satisfy the “foreign power condition.”

Even more disturbing, involvement of a foreign power is not actually needed if the government argues that the conduct of the defendant was “intended” to “benefit a foreign power.” In this circumstance, “it is not necessary [for the prosecution] to identify a particular foreign power.”

Therefore, for example, if a journalist known for writing articles critical of NATO reports on “restricted” material which paints the military alliance in a bad light, regardless of whether the documents were leaked to him directly or even if he simply came across them already published online, that journalist could be prosecuted, convicted and sentenced to life–if the prosecutor convinces the jury that, based on their prior reporting or public comments critical of NATO or of Western foreign policy, they intended their reporting on the “restricted material” to “benefit a foreign power.”

Which foreign power was he intending to benefit? It isn’t necessary for the prosecutor to say, as Section 24 (6) makes clear.

There are a number of other notable elements to this bill worth considering.

‘Sabotage’ and Entering ‘Prohibited Place’

Direct action might also fall foul of provisions in this bill, if the foreign power condition is satisfied.

Committing “damage” against any “asset,” inside or outside the U.K., for “a purpose that they know, or ought reasonably to know, is prejudicial to the safety or interests of the United Kingdom” is also punishable by a fine or life in prison, or both, under Section 12.

“Damage” includes “alteration” or “loss of or reduction in access or availability” to an “asset.”

Under Section 4, entering a “prohibited place” could result in a life sentence, if the person knew or “ought reasonably to know” it is prejudicial to the safety or interests of the U.K. This includes if someone “accesses, enters, inspects [including films], passes over or under, approaches or is in the vicinity of a prohibited place.”

Conceivably, direct action activists such as members of Palestine Action who have successfully shut down factories belonging to Israeli weapons manufacture Elbit Systems Ltd, would be caught by such provisions, The same goes for journalists filming them or entering a premises designated “prohibited.”

In 2018, emails and other documents belonging to the Institute for Statecraft’s Integrity Initiative, a now defunct U.K.-based, intelligence services-linked, propaganda and psyop organization, were hacked and published online.

The documents revealed that the Integrity Initiative was receiving funding from the U.K. Foreign Office, Facebook, NATO and neoconservative-linked foundations, and was engaged in directing anti-Russian, anti-left and pro-NATO propaganda towards the European and U.K. public.

Integrity Initiative documents, including emails and a contract with the U.K. Foreign Office, revealed an ambitious global agenda involving secret “clusters” of academics, journalists, policy makers and national security-linked officials in Europe, North Africa and North America, with more being planned.

The hacked documents revealed that the purpose of the Integrity Initiative was to shape public opinion and public policy under the guise of combatting Russian “disinformation.”

A group called Anonymous Europe claimed responsibility, though the Foreign Office and Western media suggested, without evidence, that the Russian government was somehow behind the hack.

The BBC even reported, also without evidence, that the documents were “leaked to the Russian media.”

In fact, the documents were published on an internet messaging board and available to anyone aware of the website, including independent British and American journalists who reported upon them.

Reporting on such documents, if the National Security Bill becomes law, could be considered a violation of Section 1, given that some of the files were “restricted” government documents and the Integrity Initiative was partially government funded. If foreign government actors were involved in hacking or releasing the documents that alone could satisfy the “foreign power condition” in Section 24.

Even the fact that journalists (including British citizens) who were writing for foreign government-funded news outlets reported on the documents could satisfy the “foreign power condition.”

Even more disturbing, involvement of a foreign power is not actually needed if the government argues that the conduct of the defendant was “intended” to “benefit a foreign power.” In this circumstance, “it is not necessary [for the prosecution] to identify a particular foreign power.”

Therefore, for example, if a journalist known for writing articles critical of NATO reports on “restricted” material which paints the military alliance in a bad light, regardless of whether the documents were leaked to him directly or even if he simply came across them already published online, that journalist could be prosecuted, convicted and sentenced to life–if the prosecutor convinces the jury that, based on their prior reporting or public comments critical of NATO or of Western foreign policy, they intended their reporting on the “restricted material” to “benefit a foreign power.”

Which foreign power was he intending to benefit? It isn’t necessary for the prosecutor to say, as Section 24 (6) makes clear.

There are a number of other notable elements to this bill worth considering.

‘Sabotage’ and Entering ‘Prohibited Place’

Direct action might also fall foul of provisions in this bill, if the foreign power condition is satisfied.

Committing “damage” against any “asset,” inside or outside the U.K., for “a purpose that they know, or ought reasonably to know, is prejudicial to the safety or interests of the United Kingdom” is also punishable by a fine or life in prison, or both, under Section 12.

“Damage” includes “alteration” or “loss of or reduction in access or availability” to an “asset.”

Under Section 4, entering a “prohibited place” could result in a life sentence, if the person knew or “ought reasonably to know” it is prejudicial to the safety or interests of the U.K. This includes if someone “accesses, enters, inspects [including films], passes over or under, approaches or is in the vicinity of a prohibited place.”

Conceivably, direct action activists such as members of Palestine Action who have successfully shut down factories belonging to Israeli weapons manufacture Elbit Systems Ltd, would be caught by such provisions, The same goes for journalists filming them or entering a premises designated “prohibited.”

In the 1964 case of Chandler v Director of Public Prosecutions, the U.K.’s highest court upheld conviction of members of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament for violating the Official Secrets Act. The activists were convicted for entering Wethersfield RAF base “a prohibited place” for a purpose deemed “prejudicial to the security of the state.” The trial judge was said to be within his right to deny the defendants the ability to offer evidence or cross-examine witnesses to argue that their purpose in entering the base was to improve the U.K.’s security.

This is the same case that held that what is “prejudicial” to the “safety” or “interest” of the country is up to the government of the day to determine.

Protecting Corporate Secrets

Section 2 of the bill also creates a crime of “obtaining or disclosing trade secrets.” As is the case with Section 1, this occurs whether the person knew or “ought reasonably to know” that their conduct is “unauthorised.”

A person faces either a fine or up to 14 years in prison, or both, if they are convicted.

There is no whistleblowing, journalistic or public interest protection provided in this section either.

Arguably, obtaining or disclosing “trade secrets” which could reveal, for example, corruption, environmental pollution, labor violations and other human rights abuses or other forms of corporate malfeasance could conceivably result in prosecution under this bill.

The foreign power condition must be satisfied for Section 2 to apply, which, it has already been shown, is arguably easier to do than one might think.

Limiting Legal Aid Access

Access to legal aid is also restricted for anyone convicted of a “terror” offence. This means that someone who, for example, was convicted for violating Schedule 7 of the Terrorism Act 2000–for refusing to give access to their mobile phone password at the airport–could find themselves denied legal aid years later.

Freezing Funds and Other Assets

The ability of the government to “freeze” assets is also made easier in the Bill. The law currently permits freezing and seizing of assets if it can be shown that they are “intended to be used” for terrorism. This is replaced in Section 61 and Schedule 10 with the lower threshold of “at risk of being used” for terrorism.

State Crimes Committed Abroad

Interestingly, Section 23 amends the Serious Crime Act 2007 to note that it can’t be used to prosecute members of MI5 (Security Service), MI6 (Secret Intelligence Service), GCHQ or the armed forces, for any criminal conduct committed outside the U.K,, if their criminal conduct is deemed “necessary for the proper function” of those institutions.

Leaking and Direct Action

When the National Security Bill was first revealed, a number of observers seemed somewhat sanguine about it on the basis that the foreign power condition needed to be met before a conviction could be secured under Section 1.

The Freedom of Information Campaign, for example, tweeted:

When journalist Richard Spence asked about the potential life sentence, they replied:

Since then, however, the Freedom of Information Campaign, jointly with Article 19, submitted a brief for MPs making clear that journalists and civil society activists who receive some foreign funding and yet are engaged in “legitimate activities” could be caught by this bill.

The Bill appears to have cross-party support (with few dissenters) amid seeming hysteria over alleged Chinese government influence operations.

Laws are versatile and can, if not strictly drafted, be used in circumstances that even the original drafters had not intended. All it requires is for a prosecutor to be willing to bring a case and for a judge to allow it to go forward.

Beyond Stated Purpose

The Espionage Act is a perfect case in point. Ostensibly created to protect the U.S. from German spies during WWI, it was used to successfully prosecute people for their opposition to their country’s involvement in the war. Their convictions were upheld on appeal despite the fact that the First Amendment protects freedom of speech and freedom of the press.

Decades later the administration of Richard Nixon used the same act to prosecute Pentagon Papers whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg. The governments of George W. Bush and Barack Obama would then use the law, again to target whistleblowers such as John Kiriakou who revealed C.I.A. torture, Jeffrey Sterling who used official channels to blow the whistle on a dangerous and ultimately botched plot to undermine Iran’s nuclear program and Daniel Hale who revealed that 90 percent of those killed by U.S. drones in Afghanistan were civilians.

Now this same 1917 law is being used to prosecute Assange, an award-winning journalist, for publishing “restricted” documents while based outside the U.S. and the U.K.

During a debate, Margaret Ferrier, an independent MP from Scotland, asked whether the home secretary has “considered the dangers to freedom of the press that the National Security Bill presents.”

“Many of my constituents,” Ferrier added, “are concerned that measures that could prevent journalists from publishing stories of public interest are undemocratic.”

‘Online Safety Bill’

“No, I do not see a danger to journalistic freedoms,” Minister for Security and Borders Damian Hinds replied. He proceeded to change the subject by referring to another proposed bill saying that the government is “taking stringent steps to ensure, for example, that in the Online Safety Bill journalistic rights and freedoms are absolutely to the fore, because of the vital and irreplaceable role that a free and sometimes boisterous media plays in underpinning and challenging us in our democracy.”

The Online Safety Bill, described as an “Orwellian censorship machine” by the Open Rights Group, would grant powers to ministers to censor legal content. It requires all online communications–public and private–to be monitored for “harmful content” and undermines encryption of private messenger apps like WhatsApp and Signal.

“The Online Safety Bill creates a carve out for news media organizations (defined as ‘news publishers’) who are registered with the Independent Press Standards Organisation or IMPRESS or Ofcom in the case of broadcasters,” said Monica Horten, policy manager for freedom of expression at the Open Rights Group.

In theory, this carve out means news organizations “are not subject to platform content moderation policies in the same way as everybody else.” Horten added that online platforms “are mandated to leave their content online, regardless of whether it meets their policies, or other Online Safety Bill compliance requirements.”

This censorship exemption ostensibly applies to “all content that is created for the purpose of journalism and which is U.K.-linked,” according to a convoluted explanatory note recently published by the Home Office.

Regulated media outlets will also have a fast-track complaint process if their material is taken down.

In other words, a two-tier freedom of expression between the press and everyday people.

What will happen in practice to citizen journalists, bloggers and independent and alternative outlets which are not, cannot or have no interest in being, regulated by U.K. press regulators remains to be seen.

“It will be impossible for large platforms, operating at scale, to determine on that basis who is and who is not a ‘journalist,’” Horten argued.

Ominously, she assessed that it is “therefore probable that the only way to make this provision work will be to institute a register of media.”