Runaway inflation. War. Increasingly severe energy problems. Earlier and more powerful heat waves. Arrests of scientists. Setbacks in women’s rights taking us back 50 years… Exactly 50 years. Does all this have any connection?

Actually, yes, it does.

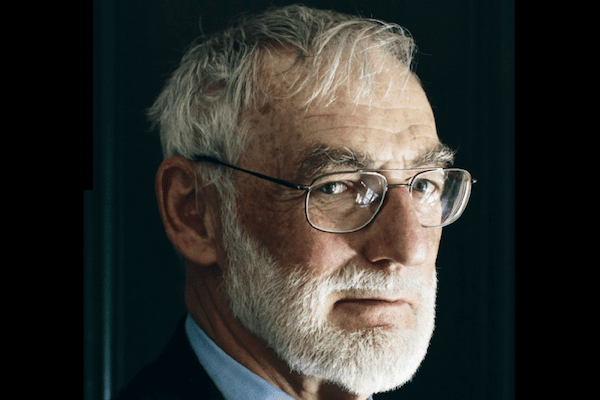

This year is special. It is the 50th anniversary of the publication of one of the most important works of the 20th century. The Limits to Growth. That work which, as early as 1972, gave a clear warning that the planet had limits and little time to face them. For this reason, one of the main authors, Dennis Meadows, has been giving interviews to some of the most important media in the world, such as Le Monde, or the Suddeutsche Zeitung.

Juan Bodera: It’s been 50 years since the publication of your book, and your World3 standard scenario is very similar to reality; you predicted that growth would stop around 2020. Is that what we’re starting to see now?

Dennis Meadows: We did not make predictions, we said it is impossible to accurately “predict” anything in which human behaviour is a factor, what we did is to model 12 scenarios consistent with physical and social rules. 12 possible futures. One of them, the “standard”, as you know, showed that growth was going to stop around 2020. Then all variables (industrial production, food production, etc) would peak and in about 15 years they would start to decline inexorably.

Does this resemble what we are experiencing? I would say yes. The world is showing more and more consequences of a crash against the limits.

What we did take great care, as early as 1972, was to make it clear that after the peak of any variable everything becomes even more unpredictable as factors come into play that could not be represented in our model. At this point it is obvious that we are going to be driven more by psychological, social and political factors than by physical constraints.

JB: I have heard you call climate change “a symptom”, of what exactly would be a symptom? can you please explain that.

DM: It is essential to recognise that climate change, inflation, food shortages are sometimes seen as problems, but are in fact symptoms of a bigger problem.

Just as a persistent headache can sometimes be a symptom of cancer, many current difficulties are symptoms of levels of material consumption that have grown beyond the limits of the planet. Of course symptoms are important. A headache deserves a response. However, an aspirin may make the patient feel better temporarily, but it does not solve the underlying problem. The uncontrolled growth of cancer cells in the body must be treated.

You can’t sustain the growth tackling problems one by one. Even if we were to solve climate change, we would encounter the next problem by continuing to grow, whether it is a shortage of water, food or other crucial resources. Growth is going to stop, for one reason or another.

JB: The myth of progress, that technology will always come to the rescue (Hydrogen, Carbon Capture & Storage…), is one of the most paralyzing ideas to face the real problem (that degrowth is inevitable) because what we need is a cultural, moral and ethical change?

DM: Yes, I agree, that was one of the crucial points of our work already 50 years ago. Ideally, technology can give you more time, but it won’t solve the problem. It can give you the opportunity to make the political and social changes that are necessary. But as long as you have a system that relies on growth to solve every problem, technology will not be able to prevent many crucial limits from being overstepped, as we are already seeing.

JB: Despite the tremendous usefulness and importance of your work, you and your colleagues were criticised a lot. This continues to happen to anyone who steps outside the dominant “wishful thinking” discourse. Is there a kind of social impossibility to talk about certain issues because you become the catastrophist, the bitter pessimist for most people?

DM: I was very naïve in the 1970s, when we launched the book. I was trained as a scientist, and I was under the impression that by using the scientific method, we produced unquestionable data, and if we showed it to people, then this would be enough to bring about a change in people’s outlook and actions. This is naïve to say the least.

There are two ways of dealing with these situations: in one you collect data and then decide what conclusions are consistent with the data, the scientific way. In the other, very common, you decide which conclusions are important, and you look for data that fits and supports your “conclusions”. This is what happens with climate deniers, for example.

I have not tried to win those debates with such people, where someone comes to me in anger and accuses me of “whatever”, I simply tell them: I hope you are right. And I move on.

JB: Systems, companies, people, usually fight for their own self-preservation, often based on short-term views that do not allow society to move forward in the long term, how to fight against these inertias and habits?

DM: Yes, the only way to manage this is to broaden the time horizon, but not only over time, but also over space. And so see the potential costs and benefits in perspective. One example: the pandemic and the management in my country [U.S.] has been woeful, very short-sighted. If you don’t extend vaccines to the whole space, they are not as useful.

How do you extend that time frame? With the next generations. Most people have legitimate, genuine concerns about the future of their children, nephews, nieces, grandchildren.

JB: In Spain we are having good news lately regarding degrowth: the first citizens’ assembly for the climate has chosen among its 172 measures the need to educate about degrowth, several political parties -including the minister of consumption- have made statements in favour of opening this unavoidable debate, the IPCC increasingly includes this word in its reports. Are we closer to a social Tipping Point -as Timothy Lenton usually says-, or will we have to wait for the crises to become even more evident to react?

DM: The answer to both questions is: yes. We are closer to a positive social tipping point, but on the other hand I fear that we will have to wait for the crises to become even more evident to react. And it is even worse: if you had described our current situation to us in, say, the year 2000, we would have thought that this was already a catastrophic crisis. We are the frog that does not jump out of the pot, overcooked. Unfortunately I think that’s our situation.

JB: According to the HANDY model, a fundamental parameter for causing collapses is inequality, which increases in parallel to the lack of trust among peers, another reason for a collapse. The design of our economic system causes both to increase every year. And it makes it impossible to adjust to the limits, because the elite–which is usually detached from reality and therefore does not detect the alarms–is the one that serves as a model. How to untangle such a mess?

DM: The truth is not to be found in a few equations, obviously. It is to be found in history. And our history over thousands of years shows that the powerful seek more power, and have an easier time finding it because of their situation–it’s a positive feedback loop. In system dynamics this is called “success for the already successful”. We rarely deviate from this phenomenon.

No one can untangle this tangle. I don’t think there is any action or law that can do that. In a few cultures, however, evolved redistribution mechanisms have been seen. In the northwest of the United States there are some tribes that have a custom called “Potlatch”, a ceremony in which the chiefs of the tribe, the richest, would give away part of their possessions–I’m simplifying for sure. In Buddhism there is also a tradition of material detachment in many of its practitioners. But these are rare exceptions. In our world the tendency is to accumulate power and, as you say, that helps to be detached from reality. Then you may end up with a collapse–even of your power–and everything starts all over again. It’s a process that happens in response to limits.

And inequality is growing in all countries.

JB: To what extent are the elites anticipating the mathematical need for greater equality and preparing for it? Or, are they just planning their own survival?

DM: Well, one cannot properly speak of “elites”. Some elites are concerned and doing all they can to reduce inequality, others are not even thinking about it–probably the majority–and others are working to make it bigger and bigger. There is certainly no trend towards reducing inequality. And sometimes it is justified that growth helps wealth to reach everyone, which, seeing how growth and inequality rates have risen simultaneously, is clearly and manifestly false.

JB: Do you see nowadays more concern about civilizational collapse in the power circles, economic and political? Or do they still keep on short term business as usual? If so, to what extent are they relating it with the work you made in LTG?

DM: I am not in power circles so I can’t answer that. I am an 80-year-old retired teacher. It is the 50th anniversary of The Limits to Growth and except for the interviews that are done about a book that still arouses interest there is not as much attention as it might seem. [interviewer’s note: and as it should].

JB: Concerning the current myopic boundaries of concern, spatial and temporal, don’t you think the modern worldview is obsolete? Could you suggest some philosophical insights to transition to a new cosmology?

DM: Thank you for imagining that I might have the capacity to do such things. That the current worldview is obsolete is obvious just by looking at the news. Hardly anyone can be happy with the state of the world.

On a new cosmology: there is a huge diversity of philosophies, spiritual practices, many of them consistent with how the world works. Any that are going to work have to recognise the interaction and dependence we have with the natural world. We have already discussed the widespread myth that technology will lead us to overcome any obstacle. We see it with the climate challenge: there is this thing called Carbon Capture and Sequestration. Despite the irrefutable fact that it is cheaper, quicker and easier to reduce energy consumption, the tendency is to look for the technological solution that will allow us to do what we can no longer do without causing serious damage. It is a total fantasy. The best we can say about CCS is that it is an idea that is going to make a few people a lot of money.

We’re like on a treadmill that’s accelerating rapidly. You know, those treadmills that you run on but you don’t go anywhere. That’s what we’re doing. As we’re making bad decisions, that throws us into crises that by force shorten our time perspective, everything becomes reactive as we accelerate. That in turn helps us make more bad decisions because we narrow our time horizon more and more. It’s a vicious circle.

I think we are going to see more changes in the next 20 years than we have seen in the last 100. I don’t want what I’m about to tell you to happen, but I think it’s most likely: there will be significant disasters due to climate chaos and the depletion of fossil fuels, which will return humanity to more decentralised and disconnected states. Slowly, cultures will evolve that are more prepared for the situation. Only then, I believe, can an appropriate “new cosmology” emerge.

JB: Do you believe a coalition of gifted elites could change course in those circles?

DM: Gifted elites? Sounds like an Oxymoron to me.