Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, U.S.-based media platforms have made an extraordinary effort to cut Western audiences off from news from a Russian perspective. When social critic Noam Chomsky pointed out how unprecedented this was, Newsweek‘s “factchecker” (7/26/22) declared his criticism “clearly untrue”—a determination that did more to confirm the ideological strictures of U.S. media than to debunk them.

Soon after Russia invaded Ukraine in February, Russia Today, funded by the Russian government, was removed from DirecTV and Dish Network (New York Times, 3/12/22), YouTube (France24, 12/3/22), TikTok, Meta (CNN, 3/1/22) Google News (Reuters, 3/1/22) and Spotify (Reuters, 3/2/22) in the United States and/or Europe. RT and Sputnik (another Russian state—funded network) were removed from the Apple app store (TechCrunch, 3/1/22).

CNN (3/1/22): “The actions taken by television providers and technology companies against RT have…reduc[ed] the Kremlin’s ability to peddle its narrative at a pivotal time.”

Motivations for banning RT and Sputnik were due to “extraordinary circumstances,” in Google’s words (Reuters, 2/26/22), and to protect “against state-sponsored disinformation campaigns” (Microsoft.com, 2/28/22). RT’s offices in the U.S. had to close down their production completely (Washington Post, 3/3/22).

PayPal has recently frozen the accounts of independent news outlets such as Consortium News (Democracy Now!, 7/12/22) and MintPress (Democracy Now!, 5/4/22; FAIR.org, 5/18/22). The circumstances around PayPal’s actions are less clear than with the actions against RT. The editor-in-chief of Consortium News, Joe Lauria, said he didn’t know why PayPal froze its account, but he suspects a clause in the user agreement against “purveying misinformation” may have been invoked (Democracy Now!, 7/12/22).

One of the many chilling effects of the media blackout was that YouTube deleted its entire archive of commentary by the Pulitzer Prize—winning journalist Chris Hedges (who formerly worked for the New York Times and NPR) because it was hosted by RT (Democracy Now!,4/1/22).

In May, the U.S. announced new sanctions against Russian television networks Channel One Russia, Television Station Russia-1 and NTV Broadcasting Company (CNN, 5/8/22), cutting them off from U.S. advertisers.

‘A kind of totalitarian culture’

Newsweek (7/26/22): “There are no justified parallels to be drawn between the Soviet Russia media landscape and that of the U.S. today.”

Noam Chomsky, professor emeritus of linguistics at MIT and a renowned media critic, responded to this consolidated effort to “counter the threat” posed by the “information war” (Newsweek, 7/26/22) in an interview with actor Russell Brand (YouTube, 7/22/22):

Take the United States today; it is living under a kind of totalitarian culture which has never existed in my lifetime, and is much worse in many ways than the Soviet Union before Gorbachev. Go back to the 1970s, people in Soviet Russia could access BBC, Voice of America, German television, if they wanted to find out the news.

Chomsky’s comments were “factchecked” recently by Tom Norton of Newsweek (7/26/22). He wrote:

While the BBC and Radio Free America did broadcast in Russia post-WWII and during the Cold War, their frequencies were jammed by the Soviet government for decades. Any access that the Russian public did have was gained in spite of, not thanks to, their government’s efforts.

The article briefly covers the history of signal jamming in the Soviet Union and other comments made by Chomsky, concluding:

To suggest that Americans have less access to information than citizens in Soviet Russia is therefore, not only clearly untrue, but an argument that neglects the sacrifices and perils that journalists have endured to deliver accurate news about the country, and continue to endure to this day.

The official ruling of Newsweek declared Chomsky’s comments false:

By all accounts, Americans are able to access news from Russia despite many Western journalists having fled the country, and Russia having blocked its public’s access to most Western social media and news platforms.

‘A ubiquitous phenomenon’

BBC (3/23/11): “Listening to the [BBC‘s] Russian Service as well as other Western broadcasters had, by the 1970s, become a ubiquitous phenomenon among the Soviet urban intelligentsia.”

Interestingly, the same New York Times article reported that “a Harvard University study in the mid-1970s estimated that 28 million people in the Soviet Union tuned in [to U.S.-funded VoA] at least once a week.’” And similarly, from the same BBC article cited by Newsweek:

However, jamming was never totally effective, and listening to the [BBC‘s] Russian Service as well as other Western broadcasters had, by the 1970s, become a ubiquitous phenomenon among the Soviet urban intelligentsia.

Using just two articles from Western sources selected by the factchecker, it seems that millions of people, including virtually all intellectuals in the Soviet Union, had access to and tuned into Western media in the 1970s, which is fairly consistent with Chomsky’s comments: “Go back to the 1970s, people in Soviet Russia could access BBC, Voice of America, German television, if they wanted to find out the news.”

Newsweek reached out to Chomsky for comment, who responded:

I was explicit. I referred to the banning of RT and other channels, comparing it with pre-Perestroika Russia when Russians were getting their news from BBC and VoA, according to U.S. studies.

A mass Soviet audience

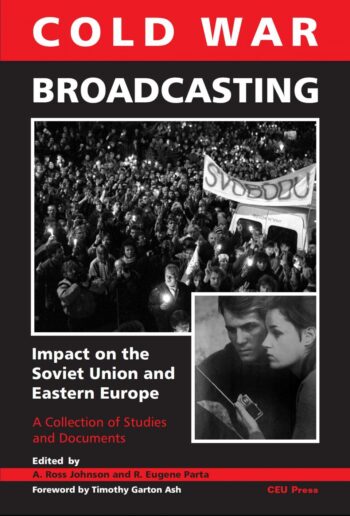

Cold War Broadcasting (CEU Press, 2010): “Some 52 million people in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe tuned in weekly to the Voice of America in the early 1980s.”

A collection of studies were published in 2010 in the book, Cold War Broadcasting: Impact on the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, edited by A. Ross Johnson, a former research fellow at the Hoover Institute (a conservative think tank) and director of Radio Free Europe (U.S.-funded media), and R. Eugene Parta, also a former director of RFE and a contributor to the Hoover Institution. The studies corroborate the claim that people in the Soviet Union were frequently listening to Western media.

In the 1970s, simulations estimated by MIT put VoA weekly listenership reaching highs of 19% of the adult Soviet population, with the BBC topping out at 11%. “Study results showed that by the end of the 1970s, more than half of the USSR urban population listened to foreign broadcasting more or less regularly,” according to Cold War Broadcasting.

Out of curiosity, what do the U.S. studies have to say about the 1980s?

Some 52 million people in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe tuned in weekly to the Voice of America in the early 1980s. That was approximately half of VoA’s global audience at the time.

The Soviet war in Afghanistan apparently did not stop people from listening to Western broadcasts. In 1984, 40% of the urban population received information on the war in Afghanistan from Western radio, and in 1987 it was 45%.

In the contemporary United States, however, this is not permitted. We cannot have people listening to the enemy in times of war.

Cold War Broadcasting noted that

the size of Western radio stations’ audience grew gradually from the beginning of broadcasting in the early post-war period to reach more than 50% of the Soviet urban population in the early 1980s.

In other words, Western radio stations had a mass audience in the former USSR. The number of regular listeners was as high as 20—25%.

Soviet listeners appeared to use their access to news from multiple perspectives to get a more comprehensive picture of events:

Despite a relatively high level of trust in Western radio stations, most listeners did not totally accept all the information they heard. The Soviet audience took a more deliberate approach to understanding information that was based on a comparison of information obtained from Soviet mass media with that from foreign radio programs.

So Western outlets and U.S. studies seem to agree with Chomsky: Despite jamming, people had access and often listened to Western sources in the Soviet Union and were critically engaged with the news at the time, especially during the ’70s.