[This article continues CAM’s series on political assassinations.—Editors]

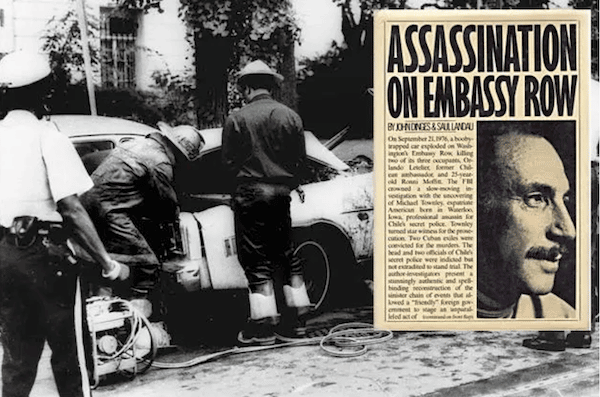

On the morning of September 21, 1976, a car bomb took the lives of Orlando Letelier, Minister of Foreign Relations and Ambassador to the U.S. under Chile’s socialist president Salvador Allende (1970-1973), and Ronni Karpen Moffitt, a 25-year-old fundraiser for the Institute for Policy Studies (IPS), a left-wing think-tank in Washington, D.C.

The Chevrolet Malibu in which they were traveling exploded near Sheridan Circle in Washington, D.C., on Embassy Row. Ronni’s husband Michael survived the bombing with minor wounds, cursing the “fascists” who had killed Letelier and his young wife.

Two years after the bombing, the U.S. Justice Department prosecuted nine co-conspirators, including five Cuban-Americans associated with the right-wing anti-Castro movement, along with an American expatriate living in Chile, Michael Vernon Townley, an explosives expert and right-wing terrorist born in 1942 in Waterloo, Iowa who worked for the Chilean security services (DINA) and CIA.1

Townley wound up accepting a plea bargain that limited his sentence to ten years (he only served five before being freed in the Witness Protection program). He saw himself as a soldier in the fight against communism and Letelier as an enemy combatant who had been carrying on a battle against the Chilean government.2

Townley claimed that DINA director Manuel Contreras, a CIA asset from 1974 to 1977, had ordered Letelier’s assassination through his chief of operations, Pedro Espinoza, and that a DINA operative named Armando Fernández, had helped him surveil Letelier.3

According to historian Alan McPherson, Contreras—who in 1995 was sentenced to seven years in prison for his role in the Letelier and Moffitt murders—was “an archetypal Cold War psychopath.” He harbored “a murderous paranoia about “subversives” and was “responsible for the murder or ‘disappearance’ of about a third of the roughly 3,000 people killed by [Augusto] Pinochet’s [fascist] regime.”

Preventing the Threat of a Good Example

An admirer of Spanish fascist Francisco Franco, Pinochet came to power in a CIA-backed coup in 1973 that ousted Salvador Allende.

Allende was a medical doctor who had helped found Chile’s Socialist Party in 1933. He had become the Nixon administration’s public enemy number one because of what Noam Chomsky once termed the “threat of a good example”—namely the institution of socialist policies that would inspire other nations to develop their economies independently from Washington.

After his election as President, Allende emphasized that Chile was “not Cuba in 1959,” in that “the right has not been crushed here by popular uprising. It has only narrowly been beaten in elections. Its power remains intact. It still has its industries, banks, land, and its allies in the army.”

Allende as such outlined a six-year program of gradual social and economic change to lay the foundations for a legal revolution from capitalism to socialism. Its aim was to establish public ownership over the country’s mines and factories, whose profits would find their way into public investment and social services rather than into the pockets of the wealthy.4

On December 21, 1970, a month and a half after his inauguration, President Allende proposed a constitutional amendment to nationalize Chilean copper because, as he explained, “the total value of all the capital accumulated in Chile over the last four hundred years has left its frontiers.”5

At the time, two major U.S. copper corporations, Anaconda and Kennecott, controlled 80% of the Chilean copper industry, which accounted for about four-fifths of Chile’s export earnings.6 Allende was willing to pay compensation, though Anaconda and Kennecott wanted millions more than what the Chilean government felt was just.7

Even before Allende’s inauguration, U.S. President Richard M. Nixon ordered a massive covert intervention in Chile code-named FUBELT, whose end goal was regime change.8

In collaboration with Chile’s upper-middle and upper classes, the CIA was committed to sabotaging Chile’s economy by fomenting strikes and “creating a coup climate by propaganda, disinformation and terrorist activities to provide a stimulus and pretext for the military to move.”9

When the coup was carried out on September 11, 1973, Allende was murdered. The Chilean military subsequently carried out hundreds of executions by firing squad and mass arrests.10

The Swedish Ambassador to Chile at the time, Harald Edelstam, who helped hundreds escape persecution, estimated that 10,000-15,000 people were killed in the first three months after the coup as the Chilean military had orders to kill anyone who resisted.11

Among those who were detained and narrowly escaped death at Dawson Island concentration camp was Letelier, a lawyer and economist who had first started his career working in Chile’s Department of Copper when he developed his support for Allende’s nationalization policy.12

One of Many Victims of Operation Condor

According to Letelier, the day after the coup, he was taken out of his jail cell blindfolded before a firing squad, though one of the sergeants yelled “Halt!” and his life was spared—temporarily.13

After his release to Venezuela, Letelier moved to Washington, D.C., to work for IPS, where he developed a study of U.S.-Chilean relations during the Allende years and began to plan for a resistance movement to General Pinochet with other exiled Chilean Socialist Party leaders.14

DINA’s assassination campaign was part of Operation Condor—a CIA-driven effort modeled after the Phoenix Program in Vietnam in which Southern Cone intelligence services coordinated their efforts to hunt down left-wing dissidents, including civilian politicians.

The U.S. government provided crucial support for Operation Condor through police training programs and the establishment of blacklists and a communications infrastructure based in the Panama Canal Zone, as well as the political backing of U.S. officials, chief among them former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger.

In September 1974, in a prelude to the assassination of Letelier, Michael Townley built a car bomb to assassinate General Carlos Prats, Pinochet’s predecessor as chief of the Chilean Armed Forces and an Allende loyalist who had the potential for leading a progressive-military coalition to overthrow Pinochet.

A year later, DINA forces tried to assassinate Bernardo Leighton, a former Christian Democrat Vice President and founder of Chile’s Christian Democratic Party, who promoted the idea of a Christian Democrat-Popular Unity (Socialist Party) alliance to restore democracy in Chile.15

Letelier was the next target because he had been a) effective in cultivating alliance with Democratic Party senators and in lobbying for the cut-off of U.S. military aid to Chile; b) had helped initiate a Dutch embargo of Chilean products; c) had denounced Pinochet’s atrocities at a large rally in Madison Square Garden; and d) was working to develop plans for a new world economy that would undercut the power of large corporations.

Just before his death, Letelier published an article in The Nation magazine arguing that the human rights abuses of the Pinochet regime were inxtricably linked to the institution of free-market economic reforms promoted by “the Chicago Boys”—or conservative economists who followed the ideas of Milton Friedman.16

Complicity of U.S. Government and CIA

The U.S. government was complicit in Letelier’s murder because of the Nixon and Ford administration’s strong support for General Pinochet’s regime and covert support for the deadly Operation Condor, of which Letelier’s murder was a part.

The same year that Letelier was assassinated, Pinochet had personally complained to then-Secretary of State Henry Kissinger about Letelier’s activities, in a conversation in which Kissinger assured the dictator that “we are sympathetic with what you are trying to do.”

Michael Townley had learned explosives skills from Frank Sturgis and CIA experts in Miami, and worked in Chile under David Atlee Phillips in an effort to block Allende’s election in 1970.

The CIA not only trained the main culprits, but also aided in the cover-up.

During the FBI investigation, it withheld information that Deputy Director Vernon Walters, a few weeks before the assassination, had learned about a covert mission in Washington by two Chilean intelligence officers, Juan Williams and Alejandro Romeral.

The CIA, then under the directorship of George H.W. Bush, had received a phone call in August 1976 establishing the presence of agents Williams and Romeral in Washington.

After the killing, the CIA promoted disinformation that DINA was innocent and that Letelier and Moffitt had been killed by a leftist so Letelier could be transformed into a martyr.17

A Death Not Entirely in Vain

Orlando Letelier and Ronni Moffitt’s assassination at the hands of CIA-trained forces provides a chilling reminder of the blowback associated with U.S. foreign policies during the Cold War.

The U.S. support for fascist regimes abroad in that period resulted in a huge spike in international terrorism that extended to the U.S. itself.

Condor-type operations could easily re-emerge today with the advent of a new Cold War, and as part of a backlash against the ascendancy of the political left in South America.

Washington’s influence, however, and appeal of fascist ideas in Latin America are not as strong as they once were.

Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, who is an heir of the Pinochet tradition, is more and more isolated in the region and poised to lose power in October elections, while socialist governments have survived recent CIA-backed coup attempts in Venezuela, Nicaragua and Bolivia.

Chile is currently governed, meanwhile, by a young left-leaning president, Gabriel Boric, who has repudiated not only Pinochet but also the Chicago Boys, saying that, “if Chile was the cradle of neoliberalism, it will also be its grave.”

This would have been music to the ears of Orlando Letelier, whose struggle for a more just economic order may yet be fulfilled.

Notes:

- ↩ According to Spartacus Educational, Townley’s father Vernon had worked for the CIA in the Philippines and was appointed head of the Ford Motor Company in Chile. In 1958, he helped fund the campaign of conservative Jorge Alessandri who narrowly defeated Salvador Allende in Chile’s presidential election.

- ↩ John Dinges and Saul Landau, Assassination on Embassy Row (New York: Pantheon Books, 1980), 362.

- ↩ Alan McPherson, in Ghosts of Sheridan Circle: How a Washington Assassination Brought Pinochet’s Terror State to Justice (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019), provides evidence that Pinochet himself gave the orders for the assassination.

- ↩ Dinges and Landau, Assassination on Embassy Row, 27.

- ↩ Idem. Allende also established a sweeping land-reform program designed to redistribute land to the poor and took measures to nationalize Chile’s banks. Economic productivity increased during his tenure and unemployment declined until the CIA joined forces with Chile’s upper-middle and upper classes to sabotage the successful socialist experiment.

- ↩ Peter Kornbluh, The Pinochet File: A Declassified Dossier on Atrocity and Accountability(New York: The New Press, 2003), 84.

- ↩ Dinges and Landau, Assassination on Embassy Row, 47.

- ↩ Kornbluh, The Pinochet File, 1, 2.

- ↩ Kornbluh, The Pinochet File, 14.

- ↩ Kornbluh, The Pinochet File, 153. When Mississippi Senator James Eaatland told Pinochet on a visit to Washington that he wanted to “hang all the communists” and “put all rabble rousers in jail,” Pinochet replied to him: “that’s exactly what I’m doing.” In Dinges and Landau, Assassination on Embassy Row, 302, 303.

- ↩ Harald Edelstam interview by Phil Ochs, July 31, 1974, Woody Guthrie Museum Archive, Tulsa, Oklahoma. Characterizing Allende as a “peaceful, cultivated and humane man,” Edelstam told Ochs that the Chilean military used tanks and bombs to destroy textile and other factories where workers tried to resist the coup.

- ↩ Dinges and Landau, Assassination on Embassy Row, 31, 32.

- ↩ Dinges and Landau, Assassination on Embassy Row, 66, 67.

- ↩ Dinges and Landau, Assassination on Embassy Row, 87.

- ↩ Dinges and Landau, Assassination on Embassy Row, 158, 161. Leighton survived the attack but his wife was left paralyzed and he retreated from politics afterwards and the Christian Democrat-Popular Unity Alliance withered.

- ↩ Dinges and Landau, Assassination on Embassy Row, 7, 11, 23, 171

- ↩ Dinges and Landau, Assassination on Embassy Row, 243.