The only Russian leader in a thousand years who was a genuine gardener and who allowed himself to be recorded with a shovel in his hand was Joseph Stalin (lead image, mid-1930s). Compared to Stalin, the honouring of the new British king Charles III as a gardener pales into imitativeness and pretension.

Stalin cultivated lemon trees and flowering mimosas at his Gagra dacha by the Black Sea in Abkhazia. Growing mimosas (acacias) is tricky. No plantsman serving the monarchs in London or at Versailles has made a go of it in four hundred years. Even in the most favourable climates, mimosas—there are almost six hundred varieties of them–are short-lived. They can revive after bushfires; they can go into sudden death for no apparent reason. Russians know nothing of this—they love them for their blossom and scent, and give bouquets of them to celebrate the arrival of spring.

Stalin didn’t attempt the near-impossible, to grow lemons and other fruit in the Moscow climate. That was the sort of thing which the Kremlin noblemen did to impress the tsar and compete in conspicuous affluence with each other. At Kuskovo, now in the eastern district of Moscow, Count Pyotr Sheremetyev built a heated orangerie between 1761 and 1762, where he protected his lemons, pomegranates, peaches, olives, and almonds, baskets of which he would present in mid-winter to the Empress Catherine the Great and many others. The spade work was done by serfs. Sheremetyev beat the French king Louis XIV to the punch—his first orangerie at Versailles wasn’t built until 1763.

Stalin also had a dacha at Kuskovo But he cultivated his lemons and mimosas seventeen hundred kilometres to the south where they reminded him of home in Georgia. Doing his own spade work wasn’t Stalin showing off, as Charles III does in his gardens, like Louis XIV before him. Stalin’s spade work was what he had done in his youth. It also illustrated his message—“I’m showing you how to work”, he would tell visitors surprised to see him with the shovel. As to his mimosas, Stalin’s Abkhazian confidante, Akaki Mgeladze, claimed in his memoirs that Stalin intended them as another lesson. “How Muscovites love mimosas, they stand in queues for them” he reportedly told him.

Think how to grow more to make the Muscovites happy!

In the new war with the U.S. and its allies in Europe, Stalin’s lessons of the shovel and the mimosas are being re-learned in conditions which Stalin never knew—how to fight the war for survival and at the same time keep everyone happy with flowers on the dining table.

The idea of the new king as a gardener is an invention of the London newspapers; the hangers-on who make their living spruiking for design commissions; and royal PR men trying to convert a hoary aristocratic affectation into woke-standard ecological identity.

Laundering ill-gotten riches into gardens for the purpose of entertaining the monarch and drawing lucrative concessions in return was an early English idea of the first Queen Elizabeth’s oligarch cronies; and so there can be no surprise when the London papers chorus their advertisements for “all the [new] king’s gardens”.

Queen Elizabeth II presenting then-Prince Charles with a Chelsea Flower Show medal for gardening in 2009; sowing meadow seeds in Green Park, in front of Buckingham Palace, in 2016. Source: https://www.ft.com/ The Financial Times’s regular garden writer, Robin Lane Fox, was not the author of this puffery. He exhausted himself on behalf of the garden of one of the well-known English oligarchs, Jacob Rothschild. Lane Fox is the only distingushed British garden writer of the post-war generation to take Stalin’s side on mimosa. “Their display in the garden is only part of their charm. Heads of mimosa are the most exquisite of scented plants for for useindoors.” Vita Sackville-West, his well-known predecessor, mentioned mimosa only to mock it (Mimosa pudica) because “the mere touch of the finger... will cause it to collapse instantly into a woebegone heap. One grows it purely for the purpose of amusing the children”.

Gardening shots are also the head of state’s signal of dual power when the prime minister is faking gardening credentials of her own.

Elizabeth Truss posing in her election constituency with shovel (left) and hoe (right), without breaking the earth. Source: https://twitter.com/

The Russian tsars constructed their palaces for a show of power without attaching much interest in the gardens, either for their power projection, or for their personal pleasure. They abhorred the idea of digging the soil—that was for the peasants, serfs. The Russian revolutionaries who succeeded them were either too poor, too incarcerated, or too often on the run to acquire the taste for or the practice of gardening.

Vladimir Lenin had a garden at his Gorky dacha near Moscow. Here he is photographed with his wife Nadezhda Krupskaya in 1922, when he was in treatment for his first stroke. Regarding the royal and aristocratic gardens before 1917, Margarethe Floryan’s book of 1996 is the only detailed account available in English. My project of 1993 to show the pre-revolutionary and post-1917 gardens of the Soviet Union had to be aborted when the photographer took a serious job at the Interior Department of the Clinton Administration. For a contemporary travel guide, click.

Count Pyotr Sheremetyev’s orangerie at Kuskovo from 1761-62. Source: https://kuskovo.vr360.ru/003/

Left: Circa 1935 painting of Stalin giving his lemon lesson, pruning pole in hand; source: https://m-partners.facebook.com/

Right: Stalin’s Kholodnaya Rechka (“Coldstream”) dacha is on the heights above the Black Sea, between Sochi in the north and Gagra to the south.

Some earnest academics claim that gardening is a political simile for the way rulers regulate the way they think those they rule should behave. For example: “In a widespread image of the late 1930s the Soviet state is represented as a garden tended by the wise and attentive Stalin. Not only does this garden naturalize the dynamic and multiethnic modern state as a single organic totality, as in Zygmunt Bauman’s notion of the totalitarian ‘gardening state’; the garden also presents the Soviet state as a new ecology (rather than just an economy) based on homologous relations between nature, technology, industry, morality and aesthetics. In the strictly aesthetic dimension the image of the garden helps define Socialist Realism as a modeling aesthetic, that is, one that is directed at providing not only a mimetic microcosm, but also a means of governing the world.”

Gardening as a diversion from working-class politics is more understandable, better documented. The dacha or small cottage garden available for cultivation by urban workers is usually reported as a Soviet invention, principally Stalin’s idea before the German war began, and then a vital home front policy during the war. However, there is a much older history of cottage or allotment gardening among British urban industrial workers of the 19th century, and an even longer record of allotment gardening for the rural British poor stretching back to the 17th century. Allotment gardens were also devised to neutralize the rebellions of unemployed and starving rural workers in the belief that the energy spent on spade work wouldn’t go to pikes and incendiary protests.

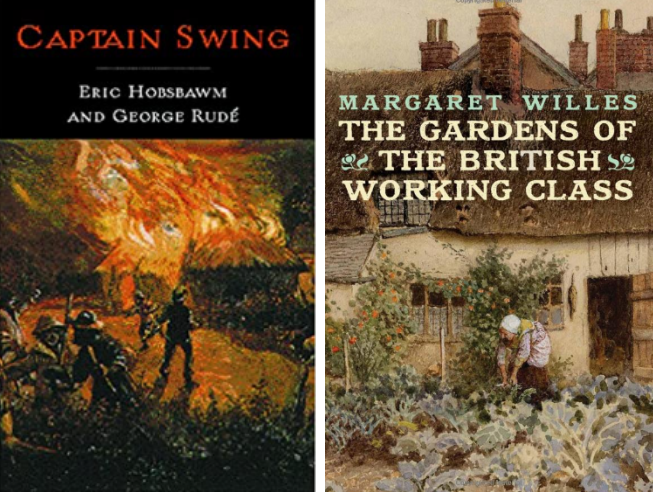

Left: Eric Hobsbawm and George Rudé’s history of the rural protests of the 1830-32 period known as the Captain Swing riots, first published in 1969. Right: Margaret Willes, The Gardens of the British Working Class, published in 2014. Just like the Soviet dachniki and their Russian contemporaries, British allotment gardeners preferred to grow potatoes. “Between 1830 and 1849”, Willes records, “potatoes came right at the top of the list , grown in 87 percent of the allotment records examined, followed by 55 percvent for wheat. In descending order thereafter come beans, peas, barley, cabbages, root vegetables, such as turnips, opinions, and carrots, with a few mentions of lettuce, fruit, and just two references to flowers.”

From the earlier British proletarian point of view, Stalin’s focus on lemons and mimosa might have been thought of as bourgeois and reactionary; Russians haven’t thought so, or dared to say it. Stalin’s spade work is another thing, and now is the time. In the present war, there is an altogether new world to grow, one way or the other.

“The future world order is being decided today… The question is whether this world order will have a single hegemon that forces everyone else to live by its infamous rules, which only benefit this hegemon and no one else… They do not have the scruples anymore to declare their intention to not only defeat our country militarily, but also to destroy and fracture Russia. In other words, they want a geopolitical entity that is too independent to disappear from the world’s political map”—Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov’s speech to the UN General Assembly, September 22, 202 2. Picture published by the Russian Foreign Ministry shows Lavrov with U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry in the garden of Winfield House, the U.S. Ambassador’s residence in London, on March 14, 2014.