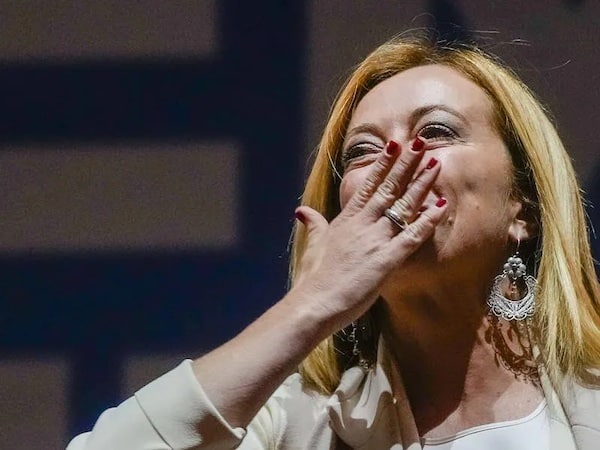

The Italian general election was a historic win for the far right. A coalition of the three major parties won 44 percent of the vote, enough in Italy’s byzantine electoral system to form a clear majority in both houses of parliament. Most importantly, it was driven by the meteoric rise of Giorgia Meloni’s Brothers of Italy, a party rooted in the post-Mussolini fascist tradition, which secured 26 percent of the vote, making it the single largest party in parliament.

For many, the ascension to power of a fascist party in the centre of Europe seemed unthinkable. But decades of grinding economic crisis, state-sponsored racism and the discrediting of parties of the neoliberal centre have created a dangerous situation of far-right advance. With Europe on the brink of yet another recession, the prospect of further descent into authoritarianism and barbarism is alarming.

If you listen to the capitalist press and politicians, however, you would think that there’s nothing to worry about. A headline in the Australian exhorts: “Relax, Giorgia Meloni’s Brothers aren’t fascist”. The Australian Financial Review carried the line, “Victory to Italian right is no lurch into extremism”. This is despite Meloni’s pledge to institute a naval blockade to stop refugee ships, roll back abortion and LGBTI rights and dismantle social welfare.

Speaking to an Italian journalist at the Venice Film Festival, U.S. former presidential candidate Hillary Clinton even praised Meloni: “The election of the first woman prime minister in a country always represents a break with the past, and that is certainly a good thing”. It’s remarkable to speak of “breaking with the past” as Mussolini-nostalgists return to power in the birthplace of fascism.

A statement from Lorenzo Codogno, a former director-general of the Italian Treasury, reveals the real reason for establishment nonchalance in the face of fascism. “They want to be perceived as a party that you can do business with and can govern the country.” Business has taken a look at this coalition of far-right racists and fascists, and decided it’s a government they can deal with, potentially making a great deal of money.

Aided by a wave of apologetics from the media, Meloni has attempted to sanitise her image to present a respectable face. During the election campaign, she reassured voters that her party had “handed fascism over to history for decades now”. But Meloni has maintained a commitment to fascist politics throughout her life. At the age of 15, she joined MSI (Italian Social Movement), the party founded by leading fascists who survived the fall of Mussolini’s regime in 1943 and wanted to work for its return. Along with a series of other former MSI leaders, Meloni founded Fratelli d’Italia in 2012 as the latest iteration of this project.

In her autobiography, I am Giorgia, she espouses the “great replacement theory”, claiming that the left is attempting to destroy Western civilisation by flooding the continent with African and Middle Eastern migrants and undermining traditional family structures. In local government, Brothers politicians have passed legislation making it harder for migrants to access social housing, and proposed laws that would make it compulsory to bury aborted fetuses in cemeteries.

Meloni will rule in coalition with the Lega, led by Matteo Salvini, who as interior minister in a previous government blocked the entry of NGO ships carrying rescued refugees to Italian shores, and Silvio Berlusconi, the infamously corrupt and venal media magnate whose Forza Italia was once the leading light of the populist right.

While the far right has been advancing in Europe since the 2008 global financial crisis, Meloni’s victory is a significant milestone. It’s the first time a party with neo-fascist roots has led a government in a major European economy. This gives a boost to the rising tide of far-right politics internationally.

Meloni’s victory comes in the immediate aftermath of the major win for the far-right Sweden Democrats. She has been a vocal supporter of the Spanish Vox Party and Viktor Orbán’s authoritarian government in Hungary. Both Meloni and Orbán were guests of honour at the Conservative Political Action Conference, the most important gathering of the American right.

Meloni’s victory was assured by the craven support that every party of the political mainstream gives to unpopular and brutal neoliberal policies, which have created massive poverty and youth unemployment and savaged living standards. The 25 September election was triggered by the collapse of the Draghi government, an unelected technocratic cabinet headed by a former European Central Bank president to oversee further cuts to social spending.

Every major party from the centrist Democratic Party to the Lega participated in this “national unity” government. Meloni’s group was the only significant force that remained outside of the coalition. As the government slowly but inevitably collapsed, the Brothers gained credibility.

The high level of abstention in the election was another important factor in Meloni’s success. The rise of the right can be put down to widespread revulsion at the political mainstream, rather than a popular endorsement of Meloni’s program. Fewer than 64 percent of the eligible population voted, the lowest turnout in history and down from an average of 90 percent in the post-WWII period. Meloni increased her vote largely by winning voters from the other right-wing parties.

Despite a history of shallow anti-establishment rhetoric, a hallmark of the far right, Meloni will likely continue Draghi’s economic agenda. Meloni has also reassured the capitalist class that her government will support NATO. Internal divisions could emerge within the coalition over the war in Ukraine—Salvini’s Lega has ties to Italian capitalists with heavy investments in Russia, and he has questioned the continuation of sanctions. Meloni will have to balance the fragile and conflicting interests of her coalition partners with her desire to remain a reliable ally of European capital at large.

What is certain is that the new right-wing coalition will intensify attacks on workers and oppressed people. It can’t be ruled out that they will attempt to curb civil and democratic rights. The Brothers have already signalled their desire for legislation to ban what they term “totalitarian” or “extremist” ideologies, by which they mean communism and Islam.

The far right’s victory is a harbinger of things to come. A recent opinion piece by Edward Luce in the Financial Times noted: “Western liberalism is still skating on thin ice”, with war and looming recession in Europe, a protracted energy crisis and far-right electoral advances making for destabilising factors in world politics.

The capitalists realise that in a crisis-ridden and polarised world, far-right governments may increasingly be an option for defending their power and privilege. They think that they are playing a clever game by normalising the new government in Italy. They believe that they can keep the fascists under their thumb, use them to absorb discontent at unpopular austerity measures and advance their economic agenda.

History tells us that fascists like Meloni, who are inspired by the monstrous dictatorships of the 1920s and ’30s, may harbour even darker aspirations for the future.