The federal government is investigating why the state of Mississippi has failed to adequately fund the Jackson water system, after the city’s water crisis left 180,000 residents without clean water for much of August and September.

The news comes as Mississippi Gov. Tate Reeves (R) has been moving to privatize the city’s water system, meaning a private company would take over the system, allegedly to improve the city’s water quality.

In truth, Jackson has already worked with two private companies on parts of its water system, although these companies do not own the infrastructure. The results have been disastrous—and in some cases, helped lead to the most recent crisis. While these partnerships differ from privatization because the city still owns the utilities, they are a harbinger of what privatization could entail.

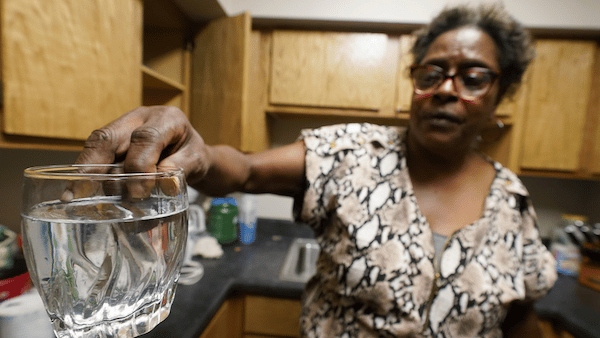

Jackson declared a water emergency in August, when rain caused the Pearl River to flood, resulting in water that could not be properly treated. Videos from Jackson circulating on social media showed water the color of coffee flowing from faucets. Residents were told to keep their mouths closed while showering, while some people had no water at all and were unable to flush toilets.

On September 15, Reeves lifted the boil water advisory after seven weeks—but the root causes of the water crisis have not been fixed. On September 16, a group of Jackson residents filed a class-action lawsuit over the water crisis, describing “neglect, mismanagement, and maintenance failures.”

Last week, the Environmental Protection Agency said it is investigating whether the state of Mississippi discriminated against Jackson, a majority Black city, on the basis of race in how it’s funded the city’s water system. And two Democratic lawmakers, including Rep. Bennie Thomspon (D-Miss.), announced they will investigate how Mississippi plans to spend $429 million in funds from the bipartisan infrastructure law allocated to improve the state’s water infrastructure.

According to Politico, the state received almost $75 million in water funding under the law this year but is spending none of it in Jackson.

The water crisis, which affected 150,000 people, was years in the making. The Lever recently reported that the credit ratings agency Moody’s helped make Jackson’s infrastructure problems worse by inflating the city’s borrowing costs.

Part of the blame also lies with the city’s work with the private companies Veolia and Siemens. Veolia, a French water, waste, and energy management company, has periodically dumped partially treated wastewater in the river, while German multinational conglomerate Siemens developed a frustratingly expensive billing system and put the city on the hook to Wall Street bondholders for more than $200 million. As a result, the city and residents found themselves with unsafe water conditions—and had less money to spend on infrastructure.

Jackson Mayor Chokwe A. Lumumba (D), who is against privatization, said in 2019:

Siemens and those working with the company failed to deal honestly with the City of Jackson… and burdened the City with one of the most expensive municipal water meter and billing systems in the country.

Privatization of utilities can have ruinous effects, because the process removes public accountability: Citizens cannot vote a corporation out of office. Citizens can also no longer meet with those in charge of infrastructure. Companies are no longer transparent to the public about their plans and operations. It also means that profits will become a main priority, making privatization expensive for taxpayers.

As the effects of climate change increase, more cities are likely to see infrastructure crises, particularly Black cities.

According to Mary Grant, Public Water for All campaign director at environmental advocacy group Food and Water Watch, Jackson’s water problems are “a story foremost about structural and systemic racism.”

The problems began in the 1980s, she said, after school integration led many white, wealthy residents to move to the suburbs. “That’s when the water system first started deteriorating,” said Grant.

And so it’s just been decades of intentional disinvestment in the system… It’s this continual legacy of intentional neglect by the state and intentional disinvestment in the system, as well as federal austerity [as] a contributing factor.

“I think [privatization] is a horrible idea that will just exacerbate the crisis,” said Grant.

If you can’t afford to improve your water system, how could you possibly afford to have profits extracted from your community just to pad the bottom line of a corporation?

Reeves’ office did not respond to The Lever’s request for comment.

“We Look Forward To The Chance To Make A Difference”

In 2010 and 2012, Jackson dumped 2.8 billion gallons of partially treated wastewater from the Savanna Street Wastewater Treatment Plant into the Pearl River.

The EPA said at the time: “When wastewater systems overflow, they can release untreated sewage and other pollutants into local waterways, threatening water quality and contributing to beach closures and disease outbreaks.” Jackson was charged by the EPA for these unauthorized bypasses.

In 2017, to try to improve the system’s efficiency, Jackson entered a 10-year deal with Veolia to operate the city’s three wastewater treatment plants. Their contract was to not only manage wastewater treatment but also operate 98 pumping stations and sludge disposal, according to a press release from the company.

John Gibson, president and chief operating officer of Veolia North America’s municipal and commercial business, said in 2017:

We look forward to the chance to make a difference in the lives of area residents through our partnership and provide opportunities for local businesses and quality of life enhancements in Jackson.

Veolia did make a difference—but not in the way residents would have wanted. The Savanna Street Wastewater Treatment Plant operated by Veolia allegedly dumped 6 billion gallons of partially treated wastewater into the Pearl River in 2020, according to a filing by federal and state environmental regulators about violations of the Clean Water Act.

Plaintiffs working on behalf of the EPA and the state of Mississippi noted that the city had not started to evaluate the wastewater system more than two years after the deadline, and they had not started its rehabilitation either.

In 2019, 2020, and 2021, the state issued advisory warnings not to swim or fish in the Pearl River due to its sewer system and overflows at the city’s wastewater treatment plants. Jackson’s contract with Veolia is still ongoing.

This wasn’t the first time Veolia was accused of making a bad situation worse. In 2015, Flint, Michigan, contracted with Veolia to improve the city’s water quality—but the following year, then-Michigan Attorney General Bill Schuette (R) sued the company. He charged them with “professional negligence and fraud, which caused Flint’s lead poisoning problem to continue and worsen, and created an ongoing public nuisance.” The charges were dismissed in 2019.

Veolia was also accused of negligence in another Flint case that was ruled a mistrial this past August, after a jury was unable to make a unanimous decision on the matter. According to plaintiffs, lead in drinking water systems caused neurocognitive injuries in four children. Lead was also found in Jackson’s water as early as 2015.

Although residents were given more than 300 boil water advisories in the past two years, doing so would not reduce lead levels and may actually increase them.

“Unprecedented And Is Contrary To Industry Standards”

In 2012, the city signed a $90 million deal with Siemens to install new water meters across the city. Siemens promised Jackson “guaranteed savings,” according to a 2019 lawsuit by the city.

In the years that followed, residents reported receiving either no bills for months or years, or bills that were inaccurately high. Siemens also worked with several subcontractors, inflating its costs.

The city has since accused Siemens of fraud. According to the lawsuit,

Siemens committed fraud with respect to who was performing the work on the project, what the system would do, and what savings the system would generate, among other things.

The city also said in the lawsuit that more than half of the 60,000 new water meters were installed incorrectly, which meant they “could not communicate with the billing system.”

Grant said the contract “led to massive erroneous bills and lack of… trust in the bills that people were receiving, because a lot of them [were] erroneous and inflated.”’

According to the lawsuit,

The City relied on Siemens, the supposed expert on these types of projects, yet Siemens failed to disclose material information regarding the project’s components and implementation.

In 2020, the parties settled the lawsuit when Siemens agreed to pay Jackson $89.8 million for fraudulent behavior and botched work, ending the contract. But the city spent that sum on its water and sewage system—and on lawyers litigating the case.

The situation left the city with little matter to spare on improving its water system—and left residents with little trust that their water woes would improve.

“They’re Trying To Extract A Profit”

Now, in light of Jackson’s water crisis, the state is allegedly in talks with an unnamed private water company to take over the system. While the city was originally involved in the discussion, Lumumba said on September 7 that the city lost that role when the state took over the discussion.

According to Grant, there are better ways to help Jackson than privatizing its water system.

“Jackson needs direct federal grants, aid, and technical assistance,” she said.

Having profiteers come in and extract even more wealth from the community, it’s not viable, and it will make matters worse.

At a September 13 town hall meeting, Lumumba, Jackson’s mayor, shared his concerns about privatization:

The problem with privatization is that companies aren’t taking over your system in order to be benevolent. They’re not taking over your system just because they want to come help, they’re trying to extract a profit from it.

He added:

And so when you have to make the level of investment that Jackson’s system requires, that means that there will be significant increases in the cost. They have looked at the margins and they are trying to understand where they get that money from. And if you privatize it then we have far less control over making sure that your rates stay affordable.

Lumumba’s office told The Lever that they were not sure what would happen moving forward with the privatization of the water system.

Grant, of Food and Water Watch, said there is usually a bidding process and request for proposals, which can take about a year. Once the system is sold, it is almost impossible to take the infrastructure back to public ownership.

As Lumumba put it at a city council meeting in August:

Privatization is, in fact, the selling of the system. And there are white papers and extensive literature that shows [the communities impacted most] are the poor communities.