Jon Melrod brings back to us a vital moment in the history of the U.S. labor movement, a moment in which the demographic transformation the workforce but also the lingering memory of 1960s social movements and unrest, raised the possibility of radicals racing to the front of class conflicts.

Fighting Times: Organizing on the Front Lines of the Class War. By Jon Melrod. Oakland: PM Press, 2022. 298pp, $19.99

From a liberal or progressive background in Vermont, Melrod plunged into the malestrom of…. the University of Wisconsin campus in Madison. A largely if not entirely middle class city, with a poor history of unionization, Madison had become by the late 1960s a hyper-hot center of campus antiwar activism. At its peak, this activism drifted into unionization (my own first union experience: the Teaching Assistants Association) but also in support of Black struggles growing vivid and violent in nearby Chicago.

My time in Madison overlaps with the author’s and I can hope to see the world through his undergraduate eyes. Everything seemed possible! And even to me, but not with the same views on the tragic breakup of the Students for a Democratic Society. Among the warring factions could be found the Revolutionary Union, “anti-revisionist” in regard to Russia and China, but heartily dedicated to entering blue collar struggles where members and sympathizers had the will. There Melrod found himself a new identity of sorts, with friends and comrades ready at hand.

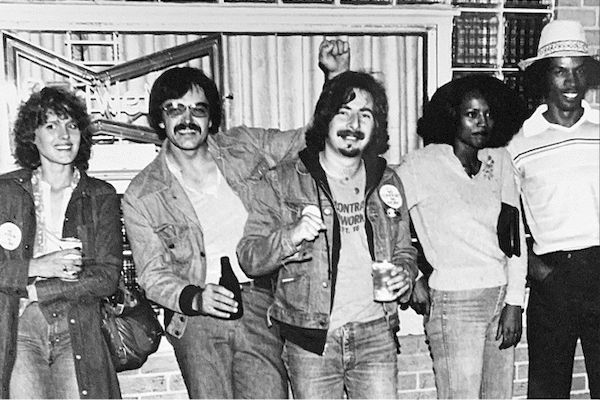

For Melrod, it was first Milwaukee, a city with an old class struggle and even an old history of socialist influence going back to the nineteenth century. The Black working class, not yet facing the massive layoffs that would wipe out good paying jobs and leave the community economically bereft, had never made it into most of the best industrial work, but fired up by the civil rights and Black Power movements, had every reason to join struggles at hand.

Our protagonist offers us day-to-day and sometimes hour-to-hour accounts of his struggles in the factory community to unite workers, and also his efforts to distribute the Milwaukee Worker, a offshoot of RU activists if intended for a wider radicalized audience. He had no good reason even to enter industrial work except for his determination, and good reasons not to accept a reality of dangerous toxins all around him (eventually, he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer).

A huge proportion of the “colonizers” from campus to factory in that time, through every leftwing group that made the effort, ran up against a brick wall. The layoffs and then shutdowns were coming, and even before they came, the recession of the 1970s lowered prospects. But this is retrospect, and the enthusiasts who went at the work sometimes had remarkable, if mostly short lived, results. Jon managed to become a rank and file leader in UAW Local 72, eventually being elected steward, chief steward, and before he left, to the top office in the executive/bargaining committee.

In time, the factory work moved to Kenosha, then a more-or-less thriving, race-mixed community with a progressive labor tradition and even a weekly paper of its own (actually shared with nearby Racine). Here, the familiar clashed with the unfamiliar as some of the workers remained from Milwaukee, joined by a new crew with different experiences. He and his fellow activists gathered around them fellow workers resistant to concessions, even as the likelihood of continued production waned steadily. Fighting Times had replaced the Milwaukee Worker, precipitating an AMC defamation lawsuit against three stewards (including himself) and a hearing with some fifty witnesses defending the rebels. One might say that by this time, determination can be said to have replaced sky-high expectations of near-time global transformation. It was also time for our protagonist to move on.

Jon had already made plans to leave, “thirty five in June 1985, still young enough to pursue another path.” He went to law school in San Francisco and after a bout with cancer, shifted into becoming a real leftwing lawyer, defending political refugees. Find more about that on www.jonathanmelrod.com