Seneca Lake’s picturesque setting belies its long history of conquest and extraction. Situated on the ancestral and unceded territory of the Onöndowa’ga:’ (Seneca Nation) of the Haudenosaunee confederacy, its shoreline has been occupied by European settlers since at least the late eighteenth century. By the late nineteenth century, the landscape was riddled with mineral mines and brine wells, fueling a booming but environmentally hazardous salt industry. In 1941 the federal government seized, burned, and bulldozed hundreds of homes east of the lake to make way for the ten-thousand-acre Seneca Munitions Depot. Now a Superfund site, the depot also became an inadvertent haven for the world’s largest herd of white deer, whose striking pelts are due to a “recessive gene”—not, locals were assured, to the presence of undisclosed nuclear warheads rumored to have been held in the facility’s hundreds of concrete bunkers.

As if giving voice to this tumultuous history, loud and mysterious booming sounds called the “Seneca Guns” have long been known to echo across the lake. This phenomenon, which continues to elude scientific explanation, has been variously attributed to earthquakes, gas bubbles, supersonic aircraft, and the “Great Spirit continuing his work of shaping the earth.”1 Two years ago, however, a new but similarly perplexing element was added to the Seneca soundscape—the constant hum of Bitcoin mining rigs.

Emerging in the wake of the 2008 financial collapse, Bitcoin is a digital asset, or so-called “cryptocurrency,” invented by a shadowy figure known by the pseudonym Satoshi Nakamoto. A supposed alternative to government-issued “fiat” currencies such as the U.S. dollar, Bitcoin is decentralized and delimited by design. Bitcoins can be “mined” by solving increasingly difficult mathematical puzzles, a process which requires the constant deployment of ever more powerful computers. This energy-intensive mining process is also used to verify transactions on a publicly distributed, append-only ledger, or “blockchain.” Because a certain amount of computational effort is required to verify each transaction, this process is called “Proof of Work” (PoW) cryptocurrency mining.

As the name cryptocurrency implies, Bitcoin was originally intended to function as a relatively stable unit of economic exchange. Over time, however, it increasingly came to function as a speculative financial asset—something that an investor purchases with the hope of selling it later at a profit. One such investor was the Connecticut-based private equity company Atlas Holdings, Inc., which in 2014 had acquired the decommissioned Greenidge coal plant on Seneca Lake. Atlas had converted Greenidge to burn natural gas, with the plan of running it as a “peaker” plant whenever the demand for (and thus price of) electricity was highest. With Bitcoin prices on the rise, however, it became clear that Greenidge could make more money through PoW mining than it could by selling electricity to the grid. Greenidge began commercial Bitcoin mining in 2020.2

The pivot to Bitcoin raised the ire of many of Greenidge’s neighbors. Instead of running occasionally as a supplement to the community’s electrical grid, the plant now ran constantly while generating nothing but seemingly “fake” money for Greenidge’s owners. The most immediate nuisance was the noise produced by the tens of thousands of high-powered computers installed in the plant. “I hear the hum of the Greenidge Plant mining its bitcoin though my windows are closed,” one nearby resident wrote to the state’s Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC). “Outside, the sound of the plant is more like roar. … I often close my windows and turn on the air conditioning to shut out the sound and, sadly, the lake breezes we so love here.”3

Greenidge emits hundreds of thousands of tons of CO2 annually—the equivalent on average of tens of thousands of U.S. households.

Less immediate, though no less concerning, are the plant’s adverse effects on air and water. To keep the rigs running, Greenidge emits hundreds of thousands of tons of CO2 annually—the equivalent on average of tens of thousands of U.S. households. The intake pumps for its cooling water lack screens to prevent fish entrainment, leading locals to describe them as gigantic fish blenders. While Greenidge has made much of its contributions to the local economy—increased tax revenues, some forty-eight new jobs, and a donation to the local fire department—many are still concerned that the plant’s environmental impact will harm both public health and the agritourism-based economy of the region.4

A number of local scientists have joined in the fight against Greenidge, including engineering professor Anthony Ingraffea, biogeochemist Robert Howarth, biochemist Greg Boyer, and economist Eswar Prasad. Ingraffea, an emeritus professor at Cornell University, had spent much of his career conducting oil industry—sponsored geophysical research only to be blackballed once he began to voice environmental concerns. Howarth, a member of the state’s Climate Action Council, has also faced industry-led pushback against his 2011 work showing natural gas (primarily methane) to be a much more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide and, therefore, not as viable a “bridge fuel” as the fossil fuel industry had claimed.5 Boyer, who directs the Great Lakes Research Consortium and is a faculty member at the State University of New York’s College of Environmental Science and Forestry, prepared an affidavit in 2017 warning that heated water from the plant could increase harmful algae blooms. His statement was used in a lawsuit filed by environmental groups and dozens of local property owners against a local planning board that had allowed Greenidge to expand its operations. A county judge dismissed the case last April, however, arguing that the petitioners “failed to establish that they would suffer an environmental injury different from that suffered by the general public” and therefore lacked legal standing.6 Prasad, a Cornell professor and senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, has testified to the environmental costs of PoW mining and Bitcoin’s failure, contrary to supporters’ claims, to serve as a stable medium of exchange.7

New York State Assembly Member Anna Kelles (also a scientist by training) has led an effort to institute a two-year moratorium on the renewal or expansion of fossil fuel power generation for cryptocurrency mining. The bill passed both houses of the state legislature in early June 2022, though as of this writing Governor Kathy Hochul has not committed to signing it into law. Notably, New York City Mayor Eric Adams—who reportedly took his first few paychecks in Bitcoin, losing thousands when the price later collapsed—has personally asked Hochul to veto the bill.8

Because the moratorium does not apply retroactively, however, Greenidge will be allowed to continue its PoW mining even with the governor’s signature. For that reason, the main legal battle over Greenidge has concerned the status of its environmental permits. The plant’s air emissions permit expired in September 2021, but Greenidge has been allowed to continue operating in spite of DEC commissioner Basil Seggos’ acknowledgement that the plant has “not shown compliance with NY’s climate law.”9

The actual contents of the comments, however, clearly expressed a massive popular opposition to Greenidge and PoW mining in general. “Given the climate emergency staring down at all of us,” wrote one Rochester resident, Bitcoin mining represents “a crude, blatant form of insanity.” Another commenter, who lives a mile north of the plant, expressed concern that Greenidge’s Bitcoin operation will “adversely impact our water quality, degrading the pastoral nature of the region and damaging vital environmental resources and our health.”

Spurred by public outrage, DEC did deny the plant’s Title V air permit on June 30th. By allowing an administrative appeal of the decision, however, regulators have given Greenidge a legal path forward by which they may be able to continue their operation almost indefinitely. The case of the permit decision deferral, moreover, shows how public demands for effective governance can be deployed as an excuse for regulatory inaction. As is often the case, what the industry lacks in popular support it has tried to make up for in money. Greenidge has hired at least four lobbying firms to advocate on its behalf at the state senate, assembly, and governor’s office. One such firm, Greenberg Traurig LLP, has sixteen registered lobbyists working for Greenidge in return for a $15,000 monthly retainer. Greenidge president Dale Irwin, meanwhile, has donated thousands of dollars to the campaigns of Greenidge-friendly politicians like Thomas O’Mara and Philip Palmesano. Beyond Greenidge, cryptocurrency interests have spent over a million dollars currying support at the state level.

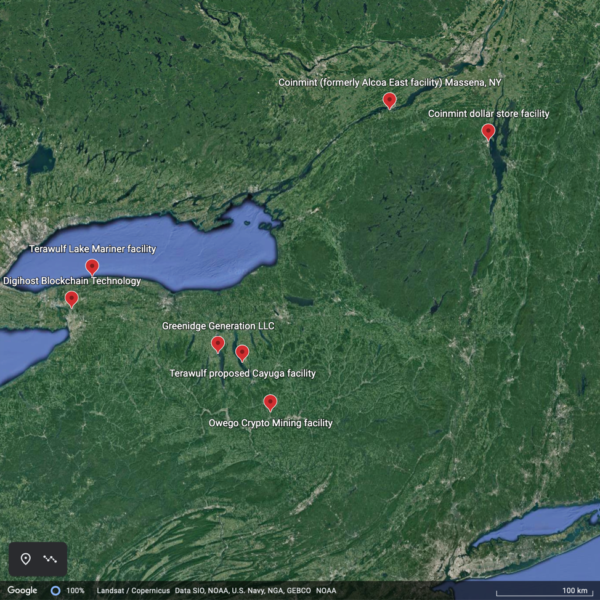

What cryptocurrency’s critics and supporters agree on is that the Greenidge case represents an important precedent for how similar crypto-mining operations will be regulated in the future. Between its relatively inexpensive electricity costs and its numerous underutilized industrial facilities, upstate New York and other parts of the American rust belt are becoming meccas for cryptocurrency start-ups.10 In New York alone, at least five current or former power plants are being turned into Bitcoin mines. The Canadian blockchain company Digihost, for example, recently fired up its Bitcoin rigs in the former Fortistar natural gas plant in North Tonawanda, a city near Buffalo. Residents have complained about the noise produced by the mining operation, and even filed a lawsuit against Digihost. Once again, a judge dismissed the suit based on lack of standing.11

Given the climate emergency staring down at all of us, Bitcoin mining represents a crude, blatant form of insanity.

The fight against Greenidge continues, with activists turning their attention to the plant’s water permits. The plant’s cooling system draws up to 139 million gallons of cold water per day from the lake, discharging it at an elevated temperature into the Keuka Outlet. There is ample room for interpretation, however, between the various stipulations regarding water temperature limits. For example, whereas the plant’s DEC-issued State Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (SPDES) permit allows for discharge temperatures of up to 108 degrees Fahrenheit during the summer, another regulation forbids discharges into trout streams (such as the Keuka Outlet) from exceeding 70 degrees.12

On top of these sorts of regulatory ambiguities are questions of credibility and accuracy regarding specific sampling practices. Greenidge is paying a third-party contractor to conduct a required thermal discharge study, for example, a client-contractor relationship that some activists worry might bias the findings in favor of Greenidge. Though these permits are due for renewal at the end of September, few expect the DEC to act any more decisively than it has with respect to the air permits. With Boyer’s help, however, residents have begun to install their own water temperature sensors on private docks near the plant. The independent data these sensors provide may prove useful in challenging Greenidge’s claim to be operating within regulatory limits.

With the continued volatility of the price of Bitcoin, however, there is always the possibility that Greenidge’s mining operation will simply cease to be profitable. By mid-June of 2022, Bitcoin’s market price had fallen more than 70 percent from an all-time high in November 2021.13 Tether, USD Coin, and other so-called “stablecoins” needed to convert assets like Bitcoin to actual currencies also seem to be buckling under the price collapse, as are crypto lending and exchange firms like Celsius and Binance.14 Greenidge’s stock has in turn plummeted since it first went public last year, and multiple law firms are assembling class action suits on behalf of shareholders, many of whom claim to have lost their entire life savings.15

The circuits used in PoW mining are so application-specific as to preclude repurposing, so if and when the cryptocurrency bubble does burst for good, the mining rigs in Greenidge and elsewhere will most likely be transformed into many tons of e-waste. Perhaps the energy the plant generates will once again be put towards the production of use values—lighting and heating homes, for example—instead of being consigned to the realm of fictitious exchange value. Perhaps the plant will once again fall dormant and become another hulking monument to American deindustrialization. The Greenidge plant’s fate remains to be seen, but from the perspective of its opponents, it is hard to imagine the facility being put to a more deleterious use than its current one.

Notes:

- ↩ Cindy Ramsey, “Booming Interest: The Mystery of the Seneca Guns,” Wrightsville Beach Magazine, May 28, 2019, wrightsvillebeachmagazine.com.

- ↩ “Our Story,” Greenidge Generation Holdings, accessed August 2, 2022, greenidge.com.

- ↩ Donna Rae Sutherland to Christopher Hogan, “RE: Greenidge Generating Power Station, Dresden, NY,” Email, November 11, 2021 (obtained under the Freedom of Information Law from New York State Dept. of Environmental Conservation; requested on March 15, 2022; received March 20, 2022).

- ↩ “Greenidge Generation Expects to Pay over $3M in State, Local Taxes,” The Chronicle-Express, January 28, 2022, www.chronicle-express.com; John Christensen, “Greenidge Donates $25,000 to Dresden Fire Dept,” The Chronicle-Express, January 27, 2021, www.chronicle-express.com.

- ↩ Christensen, “Greenidge Donates $25,000.”

- ↩ Anil Oza, “Two Professors Faced Years of Harassment for Defying the Fossil Fuel Industry. Now, They Are Reframing the Discussion around Fracking,” The Cornell Daily Sun, November 16, 2020, cornellsun.com. Standing is the legal right to initiate a lawsuit. It requires a person to be sufficiently affected by the matter at hand.

- ↩ Renata Stiehl, “NY Supreme Court Judge Rules in Favor of Greenidge Generation in Legal Decision,” WENY News, April 8, 2022, www.weny.com.

- ↩ Blaine Friedlander, “Bitcoin Mining Yields Climate Chaos, Faculty Tell NYS Assembly,” Cornell Chronicle, November 3, 2021, news.cornell.edu; Chris Sommerfeldt, “NYC Mayor Adams Has Lost as Much as $5.8K on Crypto Investment Due to Market Volatility: Daily News Analysis,” New York Daily News, May 12, 2022, www.nydailynews.com.

- ↩ Zach Williams, “Adams Urges Hochul to Veto Fossil Fuel-Fed Crypto Mining Moratorium,” New York Post, June 13, 2022, nypost.com; Peter Mantius, “DEC Commissioner Basil Seggos Says Greenidge Generation’s Bitcoin Effort Does Not Comply with New York State Climate Law,” Fingerlakes1.com, September 9, 2021, www.fingerlakes1.com.

- ↩ MarinaraHQ and orbert_melson, “Greenidge Power Network,” LittleSis, March 19, 2022, littlesis.org.

- ↩ Lily Jamali, “Crypto Miners Came to Upstate New York for Cheap Energy. Some Regret Letting Them Come,” Marketplace, March 11, 2022, www.marketplace.org.

- ↩ Thomas J. Prohaska, “Judge Dismisses Lawsuit against North Tonawanda Crypto Plant, but Calls on Owners to Keep Noise Down,” Buffalo News, March 3, 2022, buffalonews.com; New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, “SPDES Final Permit Modification,” Law Office of Rachel Treichler, September 5, 2019, treichlerlawoffice.com.

- ↩ ASA Analysis & Communication, Greenidge Generating Facility Thermal Discharge Study Plan(Dresden, NY: Law Office of Rachel Treichler, December 2020), treichlerlawoffice.com.

- ↩ Anthony Cuthbertson, Adam Smith, and Vishwam Sankaran, “Crypto Crash Live: Bitcoin Back up above Key Milestone, but Crypto Market below $900B,” Independent, June 20, 2022, www.independent.co.uk; Luc Cohen, “Binance U.S. Exchange Sued by Crypto Investor over Stablecoin Collapse,” Reuters, June 13, 2022, www.reuters.com.

- ↩ Tom Wilson, Hannah Lang, and Elizabeth Howcroft, “Crypto Contagion Fears Spread after Celsius Network Freezes Withdrawals,” Reuters, June 14, 2022, www.reuters.com; “Glancy Prongay & Murray LLP, a Leading Securities Fraud Law Firm, Announces Investigation of Greenidge Generation Holdings Inc. (GREE) on Behalf of Investors,” Business Wire, February 3, 2022, www.businesswire.com