Money on the Left is joined in conversation with curator Emily Ebba Reynolds & artist Nando Alvarez-Perez, co-founders of the Buffalo Institute for Contemporary Art, or BICA, in Buffalo, New York.

BICA is a new and distinctly heterodox arts organization, offering physical space for artist shows and educational seminars, as well as fiscal space for provisioning micro-grants to local artists. In 2018 Emily & Nando founded BICA, in their words, in order to “reframe contemporary art around issues of regional community, create a plurality of art worlds, and reconceive art as a practical tool which can be used to reshape the world around it.” Along this journey of re-conception, reframing, and reshaping, they’ve confronted and engaged creatively with the “money” question in its numerous and challenging forms. We talk about these as well as get Nando’s and Emily’s take on why a “jobs guarantee” is something artists should fight for.

Learn more about BICA (and discover ways to support the project) at THEBICA.org.

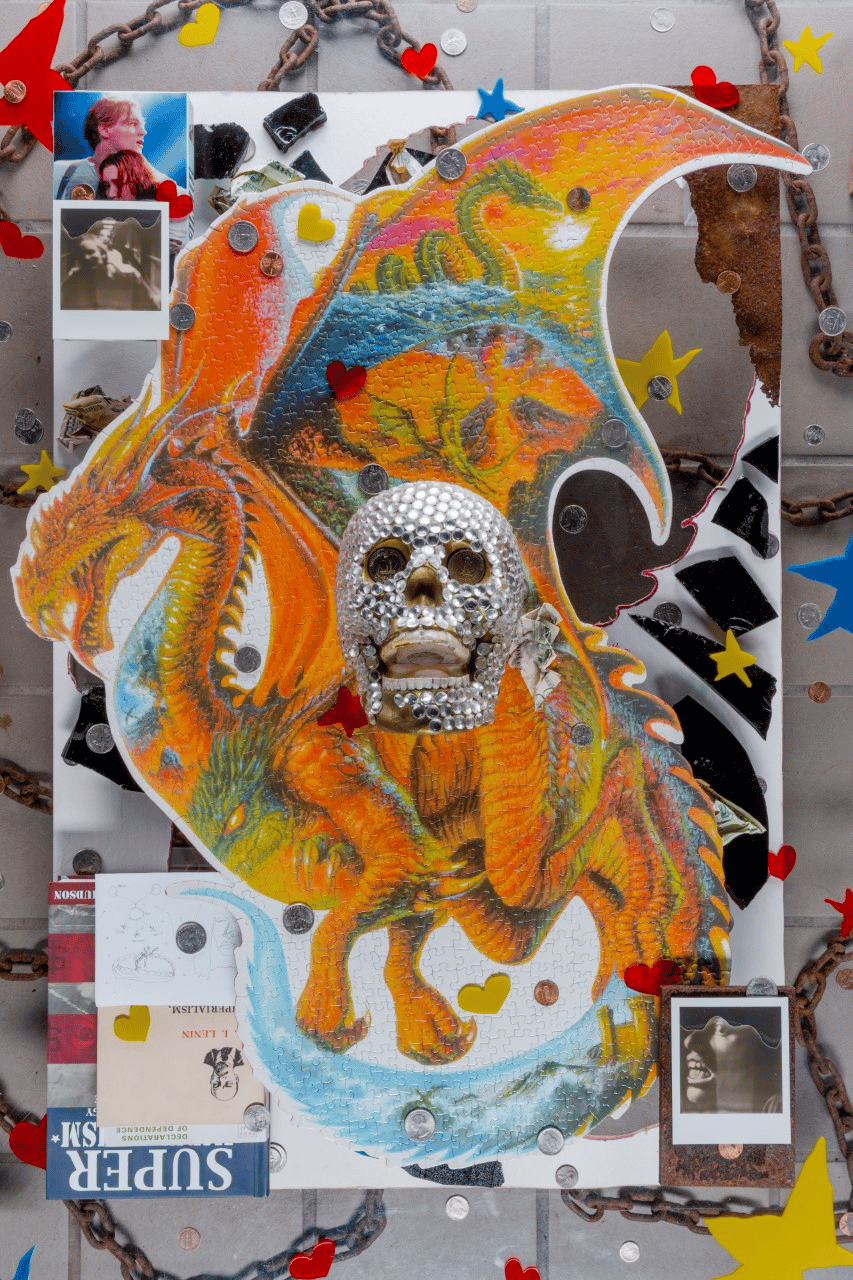

Special Thanks to Nando for lending his artwork titled, Primary Document 08262022a, for our monthly episode art. Scroll below the transcript for a full view of Nando’s piece. See if you can spot the reference to the Money on the Left crew!

Visit our Patreon page here: https://www.patreon.com/MoLsuperstructure

Music by Nahneen Kula: www.nahneenkula.com

Transcript

The following was transcribed by Jakob Feinig and has been lightly edited for clarity.

Scott Ferguson: Emily Ebba Reynolds and Nando Alvarez-Perez, welcome to Money on the Left.

Emily Ebba Reynolds: Thanks, really excited to be here!

Nando Alvarez-Perez: Thank you.

Scott Ferguson: Thanks for joining us. We’ve invited you on the show today to speak with us about the Buffalo Institute for Contemporary Art, which is known by the acronym BICA. It’s an experimental arts organization you two have co-founded in Buffalo, New York. It’s dedicated to communal practices, pedagogies, and publishing.

We’d like to highlight BICA’s accomplishments and aspirations to think together with you about how Modern Monetary Theory might help us reimagine relations between political economy on the one hand, and aesthetic practice on the other. But to start us off, maybe you can tell our listeners something about your personal and professional backgrounds to lay the land for this discussion.

Emily Ebba Reynolds: Let’s go way back, I grew up on a farm in Colorado. Then I went on to study art history in undergrad, and then exhibition and museum studies in grad school at the San Francisco Art Institute. After school, I started working at museums, I worked in marketing primarily at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts (YBCA), a multidisciplinary Art Center that, especially at the time, was more interested in shifting culture than traditional exhibitions and the more typical institutional art exhibition projects.

At the same time, I was also starting my own projects: I ran a gallery with three friends, a communally owned and run gallery. We did all kinds of exhibitions, and I also did a parking lot art fair where people could just pull up their car and show work out of them, guerrilla parking lot style. A few years ago, Nando and I moved to Buffalo, where I’ve also been working in museums and marketing, and then we also started BICA. Currently, I’m part-time at the University of Buffalo art galleries. I still got my toes in a more institutional setting, but I’m running BICA.

Nando Alvarez-Perez: My name is Nando Alvarez-Perez, and, bear with me, I stutter. I was born in Buffalo and did an undergraduate degree in Film Studies at Hunter College because I thought I wanted to work in the movie industry, and then wound up at SFAI to do my MFA in photography, which is where Emily and I met. At the time, right after grad school, I was exhibiting my work in the Bay Area, adjuncting, working in tech, wearing all the hats that artists need to wear. I am currently a visiting faculty at Alfred University.

William Saas: How did you get together and first conceive of BICA? What kinds of problems were you responding to at that point with respect to the art world and art education?

Nando Alvarez-Perez: I think we can specifically point to late summer 2017. I was doing a fellowship at YBCA, where Emily worked with the artist Tania Bruguera who was teaching an eight-week workshop about her Arte Útil program which is all about reframing arts away from traditional visual aesthetic values and norms and more about how we can re-value aesthetics through the lens of usability and practicality. And obviously, a very vague word in art, but to us, it means meeting people’s needs as they actually exist in the world.

This was the first year of Trump being in office. I think we were both really burnt out on the hustle culture of the Bay Area, of the art world there. And it felt like art promises so much for institutional and community change, that was just not feeling lived up to there. I remember I had a great run of exhibitions, and I had done work I was really proud of, but by that summer, I was feeling like this whole art game is just an exercise in narcissism. We want to think through ways that we can make it valuable to people.

Emily Ebba Reynolds: You nailed that, nothing to add!

Scott Ferguson: I used to live in the Bay Area, but you were there more recently than that I’ve lived there. And clearly, Silicon Valley Tech has increasingly overtaken San Francisco, Oakland, and the surrounding areas and made rents go through the roof. The culture is changing. What was it like to be artists, curators, students as those changes were happening?

Emily Ebba Reynolds: Everybody moves there thinking that every artist who lives there, and every gallerist that goes in there has this moment where they’re say: “Oh, obviously, we just have to figure out how to take advantage of all of this tech money.” Like there’s just some magic code that we can crack that will suddenly convince tech people to buy physical art! That was the thing. I feel like when we first started grad school, that’s what we were like, “oh, this is somebody’s just gonna do this. It’s easy.”

And then as we moved on, we realized that, no, it’s really hard to crack that nut. We would laugh at the next group of people who said, “oh, we’re just gonna sell art to the tech people.” But, they really–as a large generalization–were more interested in things like real estate and cars and watches and these sorts of more stereotypical, more material, wealthy things, instead of something that supports artists. And even when the big-time galleries moved into San Francisco, the Gagosian Gallery moved in and tried to have an outpost there, it’s closing now, they didn’t ever figure out that special way to get the tech people to pay attention. Of course, now we have NFT’s, which are questionable… well, that’s another conversation we don’t have to go into. Nando, do you want to add anything else?

Nando Alvarez-Perez: I felt we caught what felt like the last gasp of an art world there. Since we left in early 2018, a lot of curators have left, private spaces have closed down, galleries have closed down. I am laughing because our school closed as well. It first closed in March 2020 and then reopened. We were involved in rethinking what this program could look like in the future. And they were like: “no, thank you,” and went back to normal, and then they shut down. It’s one of the things that comes up in Buffalo: A lot that the Bay did have something Buffalo does not: that when you’re an artist there, you can find work in tech and actually get part-time creative work that will help you pay for artwork. In smaller places like Buffalo, there’s not as many opportunities for those intersections.

Emily Ebba Reynolds: The job quality is a little lower. I also do want to push back a little, Nando. I was just reading an article on ArtNet about this narrative that the Bay Area art scene is dead, but it’s coming back, it’s just not not mirroring the traditional art market. I think that’s something to investigate further there. But it’s certainly not easy. It’s not as easy to see what the art world is looking like in San Francisco, and it doesn’t look as traditionally successful as it has.

William Saas: When you said the “physical art” bit, I knew we were going to touch on NFT’s. Was that something that was live when you were still there? Or is that something that happened after you had skipped town?

Nando Alvarez-Perez: Definitely after.

Emily Ebba Reynolds: Nando, I remember you reading an article about a photographer who maybe did a picture of a sunflower you saw.

Nando Alvarez-Perez: Even that was around 2018. I definitely had a lot of friends who were investing in various crypto things back then–some have done very well, some have forgotten the passwords to their bitcoin wallet, ups and downs!

Emily Ebba Reynolds: That wasn’t really the art scene that we were plugged into.

Emily Ebba Reynolds: Even that thing wasn’t getting check money at the time.

Nando Alvarez-Perez: Like I said, the Gosian Gallery opened there in 2016 and then closed in 2014 and 15. They did the–I’m stuttering a lot you guys, bear with me. They did two trial runs of the Silicon Valley Art Fair, they were trying to attract artists that would make objects that tech people would like. And it was all either derived from emojis or very shiny, mirror-based things you could do a lot of looking into. They were a complete bust. I remember walking in there and on the front, they had a paintball gun attached to a drone that was making an abstract painting. That was that desperation of time.

Scott Ferguson: Wow. So where is the high-stakes art flipping market in all this? That’s in New York, that’s elsewhere?

Emily Ebba Reynolds: There are certainly people who buy new art, this happens in Buffalo too. The really rich people who buy art don’t buy art in the city they live in, it’s part of a bigger experience of going to another place, feeling like the red carpet is rolled out to you in a big fancy gallery or at an art fair. It’s not unheard of, it happens that people buy art in the city that they live in, but a lot of collecting really, especially people who have been used to living in a secondary or tertiary city, they’re used to going to a place and they like doing it that way. I think that’s a big part of it. Nando, anything else?

Nando Alvarez-Perez: Even though local people who are well-endowed and love being in Buffalo and love the Buffalo cultural scene tend to still be drawn to LA and New York. Even in the Bay Area, it was just not a big part of the culture and a lot of galleries had a hard time making it work.

Scott Ferguson: Nando, you’re obviously from Buffalo. Our next question, I think, has a partial baked-in answer, but we’d like to hear you talk about what drew you back to Buffalo. Why did you want to establish BICA in Buffalo? Maybe you can tell us a little bit about the history of Buffalo. What’s the region been like? What are the major industries? How have things changed? What’s it like now? And maybe reflect a little bit about how place shapes your thinking about arts and arts provisioning.

Emily Ebba Reynolds: I’m gonna butt in because I’m the one who convinced Nando that we should move back to Buffalo. He was resistant to it at first. When we were in the Bay Area, we were thinking about all of these problems that we’ve already covered. But another thing that we didn’t talk about is we also felt really stifled by conversations about gentrification–arts and gentrification get put together a lot, there’s definitely some chicken and egg stuff happening there. And we were concerned about anywhere we went to try to start something, if we didn’t have some kind of roots or stakes there, it being or looking like some kind of colonial enterprise.

We started to think about how either Buffalo or Colorado (where I’m from) might be the right places to have at least a historic position in the community. And Colorado has all kinds of other growth issues and we said “maybe not the place we want to dive into right now.” And when we came to Buffalo, often, it was so clear that people were actually needed here in Buffalo, we needed more people of every kind to come here.

Buffalo is a huge resettlement city for refugees and immigrants because we just literally need the population more. The other thing that really struck me in our previous trips to Buffalo was that people here seem to really care about the arts, maybe I was just recovering from the Bay Area syndrome of being like: “why doesn’t anyone care about this?” But we’d go to Nando’s friends’ parents’ houses, and they’d have original artworks they had paid for on their walls. And I said, “this is amazing, we should just, we should just be here, it seems like people care about that.” That felt like a good base to have.

Historically, obviously, Buffalo is a Rust Belt city, and it has a lot of the characteristics of most Rust Belt cities. The population has been declining, from the 60s to the last census, our current population in the city is 277,000 or so. It’s not a big city, and it does have a bigger metro area. That 277,000 also puts us as the second-biggest city in New York, which is wild, because obviously there’s a huge disparity between New York City and Buffalo.

Because of that, we’re also in this interesting position where as far as state funds are concerned, Buffalo tends to get a little more support per capita because it’s important for lawmakers to look like they’re spreading money around the state. And as the second-biggest city, you tend to have more attention than is warranted for a city of the size. The other thing that really drew us here, and that anybody who comes into Buffalo, I think, will be able to relate to, is this idea in the public imagination here that Buffalo is constantly on the edge of a resurgence. We’re just about to have our big Renaissance, party is about to start here!

William Saas: The Bills will be good this year.

Emily Ebba Reynolds: The Bills are a big part of it, and have always been, I think, but in the city that has been dealing with economic depression and struggles you could really see mental depression and emotional depression being a reality for a lot of people. There’s this strange, unending sense of, no, it’s going to get better, things are going to turn around. Which feels like a really fertile place to try something new. Nando you want to add anything?

Nando Alvarez-Perez: Not a whole lot to add there. We were thinking about where a project like this could work. Emily’s from outside Boulder and Denver where they weren’t going to solve the quality-of-life stuff and the cost-of-living issues. In Buffalo, it feels like there’s a lot of opportunities to make things happen because there’s a lot of unfulfilled and unaddressed needs. We could have gone anywhere, but we really wanted to be someplace where we felt we had real stakes and a personal connection.

William Saas: When you get back to Buffalo, you have the idea for BICA. We’d like to hear more about what y’all do. But, to set the stage: What’s the first step? We want to start an Institute for Contemporary Art in Buffalo for all these great reasons. What’s the next step? I imagine it involves money.

Nando Alvarez-Perez: The first step was that we had an idea for what we thought we wanted to do, what we thought would be a good fit. And Rock Model was a residency program that would invite artists to Buffalo. They would have an exhibition first, and then they would teach their non-art skills to non-artists. Graphic design, accounting, transcription, all of these things, but it felt with all of these new demographics moving to Buffalo, it felt like there was a need for this intersection of art and vocational work.

Then we got back there, and we spent the first year talking to people, trying to find out where we could actually be helpful. In a place that small, the vocational art stuff was fairly well covered. But we found that the regular art scene had been diminishing a bit because it had aged so much, and there were no easy on-ramps for younger audiences. Just going to a lot of exhibitions and openings and talking to younger artists there, it was clear that there were no role models, mentors, or spaces that they felt like were theirs.

That turned into the first thing we felt we could tackle. We did a pop-up in fall 2018, just to get the name out there and give people a sense for the vibe of what a BICA exhibition and opening is like. That was as part of an event called Playground, which we’re actually partnered on now, but that first edition of it was: Artists were invited to do installations in this old school, one artist per classroom.

For our pop-up, I did an artists design classroom where I made these reading books with books, beanbags and readings for all ages. Then I invited a local drag queen, Fidelia May, to do a performance about art, culture and blow jobs. I also invited my high school history teacher, who’s a local actor, to do a lecture on whatever he wanted to (this was around the time of the Brett Kavanaugh hearings). He did this this great talk about [Anne] Hutchinson, an early Jamestown proto-feminist figure who had been expelled from the community. I wrapped that up with readings for audience members.

Once we had this pop-up done, it was time to find a space. I had worked as an intern in arts organizations while I was in college here, and so I knew people who were on boards. I don’t want to go too much into the specifics of this, but there was a lot of drama with some local art organizations that people were eager to direct resources into something else. Our first base was an old mechanic’s shop on Elmwood Avenue, which is a main thoroughfare in Buffalo. It is a very tiny space and rent was quite affordable and it left room to be nimble, with what we wanted to do.

Emily Ebba Reynolds: I also want to point out that the first thing we did was start looking into how to become a 501(c)(3), and if that was the right path for us. We did try to explore non-501(c)(3) paths, which I think is important for anyone who thinks that they have to be a 501(c)(3). But in the end, for us to take the donations that we wanted to take, it made the most sense to go that direction.

Nando Alvarez-Perez: And to get the grants.

Emily Ebba Reynolds: And for grants.

Nando Alvarez-Perez: Which we knew we would need to do.

Scott Ferguson: Can you talk a little bit more about the money side of setting up this experimental community arts institution?

Emily Ebba Reynolds: Like Nando said, we had a couple of people who we had been talking to for a while and had also known Nando for most of his life at the very beginning. We were able to sell them on the idea of helping us at the start, and explained how with some upfront money, we would be able to start getting grants and doing more fundraising and keeping it sustainable on a broader level where we didn’t need just their support for as long. Obviously, we hope that everyone who has ever supported BICA will continue to, but we did get a couple of people to take a big leap with us at the beginning.

Scott Ferguson: What were the upsides and downsides of the 501(c)(3) path?

Emily Ebba Reynolds: One of the things that we’ve been actually exploring as of late –there’s ideas you can’t do, things like having a co-op that’s a 501(c)(3) but that’s actually untrue, you can. There’s something about the structure of having the board that traditionally has been a board of wealthy people who guide the decision-making of the nonprofit but often are not well versed in the work the nonprofit does, but have the ability to make huge financial and governance decisions about the organization. There’s all kinds of problems with that model, for sure. It’s based on an idea of philanthropy that comes from wealthy people who continue to have all the power and direct their funds into communities in the way that they want them to be directed.

That was, I think, our biggest concern going into it. But as we’ve done more research, and seeing that there are people really pushing on what the structure of a 501(c)(3) has to look like. Actually, none of our major donors are on our board. Our board is mostly artists and friends. It’s all people who are close to our age. It’s not the traditional–a bunch of old white men sitting in a room that you serve coffee to while they make crazy assumptions about what you’re doing.

Scott Ferguson: Stroke their beards and deciding your fates. What you’re saying is that there’s a set of normative rules and prescriptions and procedures that attend this legal category of the 501(c)3 which, for ideological reasons, have been cemented together, but are not actually part of the legal definition of the form in the first place.

Emily Ebba Reynolds: Exactly.

Nando Alvarez-Perez: It’s a pretty essential designation when it comes to donations and asking corporate sponsors for money.

Emily Ebba Reynolds: And federal and government sponsors.

Nando Alvarez-Perez: Over the last few years, we’ve also been able to act as a pass-through for other projects. I was talking about Playground, which we’re involved with now. The funding and grants we get to do that–they would not appeal to these givers if it was not tax deductible. They really want to give for the perks.

William Saas: This is something that’s front of mind for us, and probably a lot of people who are interested in starting something like BICA. I’d be interested in your experience with the first confrontation you had with the wall of bureaucracy and paperwork, and the option of a lawyer.

Emily Ebba Reynolds: There’s this guy in Buffalo, he’s a friend who is an artist and a lawyer and does this. He helps people form their 501(c)3s. It’s all he does. And so I want to say it was like, we just paid him $500. Is that right Nando?

Nando Alvarez-Perez: It was a bit more, like $750. Happy to direct all listeners to him because it was very easy. As an artist, one of the things that I’ve learned is–as an artist who also has to work and teach, I’ve learned that you just don’t always have the time to do the things you want to do. And if you have the resources to make your life a little easier on most fronts, it made things so much more smooth.

Emily Ebba Reynolds: I want to say, we opened the forms two times, and both times we’re fighting and at each other’s throats about not understanding what anything meant. And we said, let’s call that guy.

William Saas: Remarkably similar to buying drugs. You either know a guy or you’re waiting for the system to change to where it’s like… Glad you knew a guy.

Nando Alvarez-Perez: Outsourcing work, too. We do all of our own bookkeeping. But when it comes to tax time, it’s not the most affordable way to have an accountant do all that work. It’s just something I have been hesitant to tackle because there are so many ins and outs and details.

Emily Ebba Reynolds: It’s just a poor use of our time. It’s something that we’re not interested in and don’t want to do.

William Saas: You start to feel like you’re one of those conservative lawmakers, “there’s too much paperwork at the IRS”!

Nando Alvarez-Perez: I will say, the IRS these days, post-COVID, is impossible to get in touch with. It does seem like everything is delayed. If you have a problem, it’s scary because there’s no one there listening.

William Saas: This might seem like a left turn or a divergence from the conversation. But this is exactly where we want to go. The path of the IRS to the question of public funding and public provisioning and money as such. One of the things we’re interested in talking to you about and what we’re up to in every episode of Money on the Left is rethinking money and its relationship to art, aesthetics, and also social provisioning, media making.

We know that MMT wasn’t front of mind when you set up stakes in Buffalo with BICA, but it’s our understanding that you’ve encountered it and spent some time with it since. How would you say–as curators, artists, and community members invested in Buffalo and the art scene there–how has MMT aligned with and maybe informed or shaped your thoughts and decisions? Short version: What does money mean to BICA?

Emily Ebba Reynolds: MMT was not on our mind or even on our radar when we started BICA. But I do want to shout out that thinking about finance differently, or thinking about money differently, was part of our early conceptions. At the same time, as I left San Francisco, I had been working at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts and as I was leaving, I convinced them to keep me on as a project manager on a project they were working on called Culture Bank, an idea that was germinating between the director at the time, Deborah Cullinan, and this woman, Penelope Douglas, who was a pioneer in the social finance world.

I was working with them on writing case studies about artists who were contributing in non-financial ways to their communities, but in thinking about artists and community assets in a really different way than it had been traditionally thought of. That was ingrained in a lot of the language we were using, especially at the beginning of when we were talking about BICA. And when we were selling the initial donors on the project, we were already taking a financial [view] … framing things in a way that made more sense to them because they were people who thought more about money than about art.

Nando Alvarez-Perez: The default brain mode for all artists and arts organizations is scarcity, being afraid that there’s never enough. In the Bay Area, our school closed down, and obviously, somebody there had the resources to make that not happen. It sucks that that’s how it went. We came into Buffalo just preaching that more is more and more is better. And there is enough. There’s enough money, attention, and resources to be equitably shared with everybody.

Of course, once you are paying a lawyer to do your 501(c)(3) paperwork, and you’re working on a budget, and you say, “I’m going to invite these artists here for a period of X amount of time.” We install all of the work hours. So there’s still a production budget, a shipping budget, and an artist fee. We always want our artists to be paid for their work. When you’re doing bookkeeping, money becomes a very grubby material thing: in and out, in and out, in and out.

It becomes really hard to stay in that mind that there’s enough out there. We are always trying to think about ways to make the very limited financial resources that we have, make an impact beyond just an exhibition or just an artist talk. The ways that we’ve done that have been buried. You wake up one day, and it’s just like, “we can make this work,” which is amazing. And then you don’t get a grant and it’s like, “okay, well, now we need to be very practical and scrappy about how we pull this out.”

Scott Ferguson: I want to get into some of the specific projects and programs. You’ve teased us with a bunch of the different things you do. I want to get into it. But before we do, I want to ask you about the pandemic. I’ll just say in learning about BICA, and about you two and what you’ve been up to, and what you’ve been building, I came across a podcast that was recorded, I think, in 2019. It was a Bay Area arts podcast. I was listening to it from the vantage of 2022, knowing that a pandemic is coming, and you two are talking about your plans and what you’re up to, and it was all very exciting. And I just kept thinking to myself, “oh my god, the pandemic is coming. And they have no idea that they’re gonna have to try to do all this in this global emergency.” So I wanted to ask you, how did that go? How did you build all this out in the midst of a pandemic?

Emily Ebba Reynolds: I think it’s so funny that you were listening to a podcast from before, I was just listening to a podcast with my fitness guru. It’s before the pandemic and I thought, “oh, God, she doesn’t know what’s gonna hit her.” Anyways, go ahead Nando.

Nando Alvarez-Perez: That is a good way to get into the work that we do, too, because I feel like the pandemic–obviously, I don’t want to be dismissive of anyone else’s experience. But it was not a not positive thing for us. By the time BICA closed in March 2020, we had done four exhibitions in our space there, and every year of programming was designed around tackling or addressing some specific issue.

That first year of curating was about reimagining how arts institutions can be more engaged with the world around them and actually serve a purpose to their users. Each exhibition, like the first one, was when we wanted to address this issue about the younger audiences. We reached out to our friends, Bonanza, a queer, collaborative group in the Bay Area that does work that’s very campy, kitschy, fun. They’ve gotten known for their fashion shows where they make clothes out of all kinds of different things, often just garbage. We knew that these fashion shows would be a great way to draw in this new audience. They did an all-ages, all-body-types, all-experience-levels fashion show that went great.

The following exhibition was the work of Lindsay Preston Zappas, who runs an art review in Los Angeles called Carla, Contemporary Art Review LA. We asked her to come and do a show and then do an arts writing workshop. And that led to [the magazine] Cornelia, as we realized that we could produce this print publication, selling ads to local arts organizations who had nowhere else to advertise. Each exhibition came with this social-practice, community-engagement thing and they were, honestly, really hard to pull off. Each one, we felt, was tapping into a new audience and we weren’t gaining long-term traction with those people.

In early 2020, we exhibited Puerto Rican artists. We were talking about creating a float for the Puerto Rican Day Parade in August 2020. Thank God, that didn’t happen. It felt like we were just speeding up and speeding up and speeding up, and we didn’t know to what end or outcome. When the lockdowns hit, it was like, “okay, this is a good time to take stock, breathe.”

We got the magazine online, which we at first insisted would only be in print, but then it seemed like a good time to go online. And all of those social practicey engagements, we were able to re-evaluate and rethink how we want those to work at max. That’s where the impetus for the BICA School Program started, because it was a way to start building an audience for these artists, engagement and projects. Do you want to add?

Emily Ebba Reynolds: Through another organization’s misfortune–an organization that didn’t weather the pandemic as well, although I think their finances were questionable beforehand, and then the pandemic laid everything there. They moved out of this space we have moved into. Which, for us, was huge. It’s a much bigger space. We spent the first three months of 2021 building out this space to meet our needs instead of this previous organization’s needs. We’re now part of this historic art center, we get to build on this cool legacy. So we got really lucky in that moment, as well.

Nando Alvarez-Perez: The rent went down too.

Emily Ebba Reynolds: And our rent decreased, which I think we’re not the only business that figured out that the real estate market was crazy in the middle of COVID. Since we don’t depend on income from ticket sales or anything like that–it’s free to visit BICA, it’s free to pick up our magazine–we weren’t losing money. And then suddenly, there were all these new grants to help support arts organizations and increase their visibility during these times when everybody was stuck inside. Artists can often think of crazy ideas to entertain people, we were able to take advantage of some of those. Which was just lucky in positioning. Now as we emerge from a pandemic, we keep trying to remember that the feeling of speeding up and speeding up and speeding up is not sustainable. And so we have to keep remembering to not let ourselves get back there if we can.

Scott Ferguson: Tell us about the BICA School, which is different from traditional art schools you attended.

Emily Ebba Reynolds: BICA School is the most recent project we have launched at BICA. As Nando mentioned, our school started closing in March 2020 and then continued to zombify, and really closed last June, I think. As they were trying to figure out if there was a way to stay open, Nando and I served on the Committee to Reimagine SFAI where we met a lot with people who were interested in trying to keep the school open for various reasons. As we had all these meetings, I started to instill in both of our minds that the things that were most important about our education were the people we met there and the community we formed while we were in this intensive two-year program.

Nando Alvarez-Perez: To expand on that a bit, I think at BICA, a great many of the exhibitions we’ve done have been through SFAI role models, connections, and friends. Besides just being the community that was formed, it’s also the professional milieu we were able to build.

Emily Ebba Reynolds: There’s this importance of this network. The other thing that we really felt or especially that I really felt that we got out of SFAI–which was a small and scrappy school when we were there–was something about learning to do things ourselves, because the institution was not going to provide us the resources and things we needed. We needed to learn how to build the thing ourselves: If we wanted to stage an exhibition, we needed to figure out how to do that on our own because the administration was not prepared to help us with that. Thinking of those is the most important things that we got out of school. Obviously, the readings and writing papers was helpful, but I don’t go back and read my thesis very often. So I said, “oh, well, those things should be free, right? Those things are not very expensive to put together!” Yet, somehow, I graduated from art school with over $50,000 worth of debt, we don’t need to go to exact numbers.

Obviously, it doesn’t make sense, especially in a field where you know people are not going to make a lot of money. The person who goes into the art fields and makes a lot of money is a very rare breed. It doesn’t make sense for professionalized art school to cost that much. And maybe it doesn’t make sense for it to cost anything at all. With those kinds of ideas we said, “well, we should try to start this school.” And then we fought ourselves for like a year thinking, “oh, we need to set up all these structures for it.” And then, finally, we realized we are getting to that point where we’ve been talking about this to all of our friends and families for too long, and we needed to just actually do something about it.

We pulled the trigger last June and had an info session where we invited anybody who was interested in the BICA school to come and learn more about what we were thinking. We sent it to all of our audiences, but we also tried to send it especially to the universities who could make sure that people who had recently graduated from BFA programs or art programs would get it, trying to focus on Gen Z, the millennial generation. And also, obviously, there have been a bunch of people we’ve met through the years that we had been envisioning when we thought of the program. We invited all these people to come, we thought that maybe we’d get 15 people at this info session. Then we talked about it for an hour. At the end of it, we presented people with a piece of paper that asked them to commit to this journey with us for the next year.

We thought that maybe eight people might sign on to a year-long thing no one really knows what it is yet–seems risky. We thought maybe people wouldn’t want to do that. But all 30 of the people who were there signed the piece of paper. In July, we started having biweekly reading groups and critiques. At the beginning, they were mostly led by Nando and me but the group has started leading them themselves. They’re very insistent on not having a hierarchy which is great with us because the idea isn’t that we do way more work to make this happen. We provide the space and a basic framework.

Nando Alvarez-Perez: For the Money on the Left audience, maybe it’d be helpful to expand on what the traditional model of an art career is supposed to look like, which is that you are essentially regarded as untouchable if you don’t have an MFA. First you have to pay a school to get this degree that qualifies you to look good to potential buyers and galleries and also, of course, to teach. And when you exhibit your work, you’re doing it all on […], the gallery doesn’t pay you up front, you’re only paid in sales. So you go further into debt to make each exhibition happen. And teaching jobs, as you guys know well, are few and far between. We’re all in this debt scheme together.

Emily Ebba Reynolds: Especially as arts programs are cut (I’m not saying that I think that everybody should get this professional degree) but if you’re also cutting all the jobs they can go into, it’s especially confusing.

Nando Alvarez-Perez: You realize that what you get out of school is a community of like-minded peers and colleagues who will help you build a thing, and a way of being an artist in the world. You shouldn’t have to pay for that. The BICA school model is nothing new–there’s lots of examples of self-organizing alternatives to MFAs, some that have gone on longer than others. We figured we could take this core idea that what you get out of school is a community of peers and start with these basics of readings and critiques and let the users of the school develop it.

Emily Ebba Reynolds: Fear is pretty important. It’s pretty important to have fear.

Nando Alvarez-Perez: Fear helps.

Scott Ferguson: And do the participants work across media?

Emily Ebba Reynolds: Yes, we’ve got some poets who are trying to see if this is helpful for them, too. The group is all over the place, but in a way that’s fun to experiment with right now and see how it goes for everyone.

Nando Alvarez-Perez: Poets, musicians, painters, 3D printer people …

Emily Ebba Reynolds: A sex education specialist. She’s a fun one.

Nando Alvarez-Perez: It really runs the gamut. Some people are there more for critiques, some are there more for reading groups, some are there just for the energy and being involved in this thing. The last thing I’ll add is that, within about two months, it started to become clear that the participants were eager for a space of their own. We helped them lease space, it’s also in the BICA Complex, a shared workspace, exhibition space, and event venue.

Emily Ebba Reynolds: They’re running that fully collectively. They each pay in for rent as they can each month, and then are fundraising to cover the rest of their rent for the year. Again, we’ll see how it goes. But so far, they’re not very far behind, which is good.

William Saas: Much talk about finance and art in those contexts?

Emily Ebba Reynolds: We’ve talked a lot about the problems with the art market. One of the things we’d like to do as we go forward is focus on areas for multiple weeks. As we’ve gone so far, it’s been like, “oh, one person wants to read this, or another person wants to read this or last night, they wanted to listen to a Frank Ocean album,” and that went okay. I think more directed reading is probably the right thing. I think that some MMT stuff might be helpful and some thinking about how it can materialize and how artists could illustrate it might be a fun exercise to bring in.

William Saas: Maybe we can just sketch that out–what would that look like? Coming from you and your background? How would the MMT approach fit in the ad hoc curriculum?

Nando Alvarez-Perez: It’s something I’ve thought about a lot, because I’ve been very into reading about … But it’s been a tough conceptual sell.

Scott Ferguson: To you or to others?

Nando Alvarez-Perez: To others. I think people hear about the Federal Reserve and most artists’ brains just go off. It has come up a bunch of [times] Taxes are not for what you think they are. We’re working on a grant, I’ll just be very honest about this. And we’ll see how much is […] people don’t listen. We and the BICA Schoolers said, “we need to pay rent.” This grant cannot be used to pay rent. So we need to create roles for each person to pay because they really just want to pay as many artists as they can. A lot of the pandemic responses have been a spray-and-pray approach to just blasting out as much money in small chunks to as many artists as possible. I feel like the effects have not been too different than the $1,200 that we got from Trump. It just all goes into rents and stuff. But the specifics of each grant rarely allow you to put the money where you want to. For us, it’s usually overhead stuff. We are still not paid for our work at BICA. That is one thing that makes it all go round, I think. And as we’re talking about how to write this grant, we need to create facilitator roles for the artists that will then get paid. I was not there last night, but it sounds like they had a conversation clarifying that it’s okay, that they will get paid, and this pay goes back into rent.

Emily Ebba Reynolds: I said, “we can’t use this to pay for rent, but we could use this to pay each of you as facilitators.” Before I even finished the sentence, one of them said, “yeah, and we’ll pay it back in rent.” And I said, “if that’s what you want to do, that sounds good.”. I’m not gonna tell you that you can’t do it that way.

Scott Ferguson: What is that stipulation designed to do?

Emily Ebba Reynolds: All of these things are put in place because at some point, there was a problem. The past problem is that nonprofits have paid outrageous salaries to their employees, have had insane overhead costs for rent and other things, and justify why the state doesn’t want to spend money on things that are not being used appropriately.

But then, of course, it’s the thing of bad faith versus good faith. No one feels like they can trust anyone to do the right thing with the money and they’re not willing to take that leap to assume that anybody would not misuse their funds. In history, it’s not always proven that people do use their funds properly.

Nando Alvarez-Perez: We’re in the space that we are because of a mis-used grant. It definitely surprised us. We’ve had such an exciting year with the grants that we’ve gotten. And we thought that would start solving all of our problems. But the step from getting those grants to consistent staffing funding is a big relief.

Emily Ebba Reynolds: It’s really weird because it essentially asks for organizations to use private money to pay for all those things–whatever you can get from private donors. When I worked at YBCA, our biggest fundraiser each year was a dream house raffle, which is essentially gambling, right? People who never came to the organization paid money to buy tickets to possibly win a home that they would immediately have to sell because the taxes would be so high. That was the only way that the organization could make enough fundraising money that they could pay their overhead, their basic overhead of staffing, which is such a backwards way to think of it.

Instead, perhaps, we should take care of the people who are working every day and not make those positions dependent on that private money. Because then we start to run into the same thing where boards say, “oh, well, I’d like my son to do this job.” Or, “let’s make sure another white man gets to this position” and continues to sustain all the same problems.

Scott Ferguson: If we were to imagine a world of arts and arts provisioning that wasn’t austere and that was publicly supported and funded in robust ways, and included a federal Job Guarantee, which in our previous conversations you have suggested you support. What is your position in the world, your experience as artists and curators? What can you teach us folks who are really interested in fighting for a federal Job Guarantee? What should we be thinking about? What should we be arguing for from the arts world perspective?

Nando Alvarez-Perez: A couple of things. First, thinking about how many of the are-related pandemic responses to COVID have been to take usually federal money distributed to a lot of artists in fairly small amounts to do aesthetic embellishments to pre-existing programs and projects. That can be fine, it can absolutely be very helpful to put a nice artists-made veneer on top of community development program, but when I’m thinking about what a Job Guarantee could mean in the arts, I would hope that local organizations on the ground would have a way to direct the financial resources to where they see a need.

I think on the one hand, arts organizations that are always dealing with issues of staffing would all of a sudden have access to people who could handle marketing, social media and all of these things, they can really help the organization bring in more people. And then on the artist’s side, the crazy optimist in me says, “I would hope it would mean that the art world would actually decenter.” We talk so much in the arts about “art worlds” and not an “art world.” But when we talk about the Art World–big A, big W, most people have an idea of what that means. It’s the art fairs. It’s the major museums in New York and LA and Berlin. I think that if artists didn’t feel like the only way to sustain a life was to move to New York or LA, we would see artists staying where they are or going to places where they felt a real connection.

Emily Ebba Reynolds: Somewhere they just wanted to be.

Nando Alvarez-Perez: If you spend any time talking to artists from New York City… some will love it, but most are just white-knuckling it for years and then decades, hoping that things will work out. And it’s true, that is the one place where you can make a career in the arts because people actually window shop for art there. It just doesn’t happen in Buffalo. I could see artists’ evaluations of where a life could be made completely reshaped.

Most artists don’t get into the arts because they want to be a famous artist, they do it because it’s a way of using their brains that suits them, because we’ve all been sold on this idea that art is good, culture is good, the aesthetic realm can offer all these new ways to see the world. I think artists are often simply not making the work they want to make because they have to direct it towards a certain market. And I could see that the JG starts to dissolve that.

Emily Ebba Reynolds: I also think it would take some of the risk out of being an artist, when you have a sense that there’s something to fall back on. I think a lot of people are artists because they feel they always even want to be, often it’s one of those things… “oh, this is the only thing I can do.”

Nando Alvarez-Perez: Just to go back to the Bay Area, on the one hand, it’s great to have all of these jobs available to artists. On the other hand, most artists leave the arts because they say, “I can get a job at Apple? What am I doing?” There’s this constant brain drain out of the arts to other sectors. It would be so interesting to see that being reversed.

Emily Ebba Reynolds: Healthcare and having the support to not feel like you’re making a stupid decision that’s just too risky to make any sense.

William Saas: I’m thinking of David Graeber, his advocacy for something like Universal Basic Income, specifically for artists. As artists, maybe you could help us consider, as we start to wrap up, why the Job Guarantee makes sense over other possible avenues?

Nando Alvarez-Perez: I don’t want to toot our own horn, but we spend a lot of time talking to artists and organizers and community members where they are and we can get an actual sense for what their needs and resources are. Reading more about the Job Guarantee helps me reframe UBI as this libertarian dreamscape of “it would be nice to have more cash in our pockets, but what are we going to spend it on and why?” I think having those voices on the ground that can direct the work where it’s needed would make the money useful and not just inflationary.

Emily Ebba Reynolds: I want to throw out a maybe more holistic and less financial [perspective]. There are a lot of UBI programs being tested on artists right now. It’s a really common thing.

William Saas: You say tested on artists that sounds like…

Scott Ferguson: Art rats.

William Saas: Yes, art rats.

Emily Ebba Reynolds: I think they probably mostly like it. But I also think that it continues to propagate this idea of the lone artists working alone in their studio, having not a great sense of their world or their community, which I think is a really “over” idea of what art is … It’s a very capitalistic idea, a very patriarchal idea of how art works.

Funding it in a way essentially continues to be in the form of: “We’ll just pay you your salary to do whatever you want” doesn’t help the rest of the world see the value. This doesn’t really help. It’s meant for a very specific kind of artist. I think a lot of artists are perfectly happy to work in a job that helps them have a better sense of their community. They bring a lot to jobs that they work in. Obviously, I don’t want artists to have to do backbreaking labor for 40 hours a week, but I think most artists are pretty happy to see people and solve problems with them.

Nando Alvarez-Perez: I will add that this came up in a BICA School conversation a couple of weeks ago, it was at the extreme ends of a Job Guarantee, at least as we have seen it in America, is artists no longer wanting to paint WPA murals really badly. And so we get, in large part, abstract expressionism coming out of a rejection of this. You do still need to leave space, artists are going to do what artists are going to do. But I do think that they are, generally, by their nature, more other-directed than a lot of other kinds of laborers. You would still need to find some fine line there. It sounds really cheesy. I said this when we had the first info session for BICA School: “I know that when you get artists in a room, awesome things happen, and they’re capable of making things happen out of almost nothing.” Providing more opportunities and more intersections for artists to work in the real world would be awesome.

Scott Ferguson: We’ve spent a long time criticizing capitalist atomized society and artmaking. But, still, individuals do exist and Nando, you’re an artist, and you make a lot of really provocative and interesting work. Could we ask you to talk about your own work and what are your practices? What materials do you work with? What are you up to? What have you been exploring?

Nando Alvarez-Perez: Feel free to cut me short on this. Obviously working with tiny […] has made me think about BICA and Cornelia and all this stuff as an artwork of its own. Emily and I always have conversations about: “Are you an artist, Emily?” And it’s just like… who cares. Good work is being done. My own work hasn’t moved into social practice, but thinking about BICA and working through BICA has helped me reframe my own work around audience and context.

For years, I’ve been working with photography as a kernel of everything else, the work might come out in installations. I do larger installations that use extruded aluminum, there are a lot of conceptual underpinnings in the material. It’s a material you see used for trade show booths, and they’ll use it a lot in sci-fi movies and TV as a material that looks really futuristic. I think it already looks dated. It’s also often used to make things like 3D printers and cotton carve machines. Most recently, it’s been used as COVID barriers. I keep thinking I’m moving away from this one material, but it just keeps waking up. The installations use a lot of photographs I make in my studio that collapse historical movements into one flat scene. Lots of blending of both avant-garde and kitsch stuff. And then there’ll be books and beanbags and things to get people to engage with the intellectual backdrop to the work.

Two exhibitions I’ve been pretty proud of recently: I showed some work in a middle school here, where my usual work just felt overbearing and condescending to a bunch of eighth graders. I was trying to think, “what were the things that I was aesthetically into then?” It was jean patches, chain wallets,boondoggle and Tamagotchis. I was doing, you can’t see me, in quotes, “research” on YouTube and discovered the world of a VSCO girl, who’s an ecologically minded, middle schooler/high schooler who really loves to wear crocs, drinks only out of metal straws, and is really into save the whales.

Emily Ebba Reynolds: The turtles I thought.

Nando Alvarez-Perez: And there’s this whole culture of Tamagotchis. And then I got into the e-boy and e-girl scene, this post-goth internet persona.

Emily Ebba Reynolds: These things are probably so dated, I feel like they didn’t survive the pandemic.

Nando Alvarez-Perez: It was weird for me to discover that kids these days have a lot of nostalgia for the same objects that I have nostalgia for at that age. And so that show was called Eternal Flame. The Eternal Flame is a local geological feature here, open natural gas events behind the waterfall that as a kid growing up here you go to a lot. That name just seemed to work, it is calling upon the weird eternal recurrence of these consumer trends.

Last fall, I did an exhibition in a confession booth in an old girls’ middle school. That was a really fun opportunity to address conversations around disinformation versus conspiracy theories, using the confessional as a way to explore trauma, especially national traumas that are under-researched. I’m just reading about Jeffrey Epstein, weird connections to intelligent figures was really the start of that work. And I thought it would be a much longer project but then had this opportunity, this very, very, very tiny space to bring it all together. That was a lot of fun.

Emily Ebba Reynolds: It came with an essay, which I feel like was written as part of the show. The essay is part of the exhibition.

Nando Alvarez-Perez: And the text existed as a standalone piece that was about the backdrop of the work and didn’t exactly directly address it and that work was a lot of fun. Using Polaroids to take pictures out of old newspapers and off my screen and using the Polaroid, which is regarded as a very truthy medium, to start to tell these lies and shake your certainty about how an image got made and where I was in its making.

Scott Ferguson: I’m looking at this show, it’s so striking. There’s an image of JFK, a cut-out collage image where JFK’s face is like wood. And then I also see this really dark picture that looks like a clay Mickey Mouse. What are the implications or suggestions? What are the relations here?

Nando Alvarez-Perez: JFK with his head removed is an image familiar to a lot of Americans. He’s photographed with this wood veneer as the background and the wood veneer start to work their way into the work as a way to frame these works. It was just a perfect match for the confession booth architecture itself.

Veneer art has become this really interesting thing to me, because it’s a very overt lie. It’s lying to you on its surface. But you’re still supposed to act as though it’s just wood. And then the Mickey Mouse piece, I was thinking about the stories and myths that constitute our political imagination, and how over-simplified and reduced a lot of the–no offense to my fellow Americans–Americans seem to have a pretty narrow scope of how we come to believe the things that we do, and how those things relate to broader historical narratives.

Emily Ebba Reynolds: I was going to say I think there’s something–going back to that idea of what, how does this come in art? I feel like that’s something Nando might be working towards. But something about that art has often–art in the broad sense to television, and movies, and all kinds of music–have helped people sometimes see those moments when a deeply held truth is not true. And something like the way that money works, or that they’ve been told budgets work on the federal scale–these are the kind of things that maybe someday artists can help make a little space for people to think more imaginatively about.

Nando Alvarez-Perez: That was a great way to tie it all.

William Saas: Excellent.

Emily Ebba Reynolds: I’ve written some essays in my day.

Scott Ferguson: Maybe you do go back to your thesis.

William Saas: Are you working as a curator again, as we close out? Is there anything that you’re working on you’d like to talk about?

Emily Ebba Reynolds: It’s funny because now Nando and I almost always curate together, which I actually really appreciate. I have always been more of a person who likes to work on a team than alone. We’re in the middle of a series of exhibitions at BICA right now under this umbrella of recovering futures, but we’re really thinking about recovering from the pandemic in a more holistic way. That sounds really cheesy, but the artists we’re working with are in the witchy vein of recovery or…

Scott Ferguson: That doesn’t sound cheesy.

Emily Ebba Reynolds: No, it’s not cheesy. That’s the thing, we wrote a lot of grants to make it sound very cheesy because the grantors love a cheesy thing. But in reality, it’s about community healing and long-standing practices of healing that people have done together instead of medicines. Next year, we’re working on a certain entity… want to talk about the Maps to the Territory series?

Nando Alvarez-Perez: Sure. For Fall ’23 through Summer ’24, we’ve got this rough idea of looking at artists who are–now I’m thinking too hard about what we wrote in this NDA Grant–who are reframing traditionally known narratives, and well-mapped territories, through new indices. We’re showing the work of Lee Hunter, who has been working on this world-building project. They’re working in stone photography, video work, to create this future landscape and artifacts that come out of this imagined archive of a post-human future. And we’re showing the work of Maximilian Goldfarb–I would have a hard time describing exactly what he does, but he’ll take a found image of some unusual industrial objects. One thing he did was an Indian Maoist group was making IEDs, and he made a fake IED.

Emily Ebba Reynolds: He takes a picture. And then he writes an odd audio or an Alt Text description of the image. He’s working on over 1000 of them.

Nando Alvarez-Perez: Weirdly, the IED he made was used as a news photo about this actually existing Maoist group in India, which is just wild. And then finally, we’ll be selling the work of Joy Reid Minaya, a Dominican-born artist who’s been in New York for years. She tackles postcolonial narratives about the Caribbean, usually through the lens of tourism, and how tourists view the Caribbean world now.

Scott Ferguson: Thanks so much for coming on the show. Before we go, you can tell our audience how to find you online?

Emily Ebba Reynolds: We’re not Twitter people because artists tend not to live in the twittersphere. But you can find BICA @BICA.Buffalo on Instagram or at TheBICA.org. If you want to find me on Instagram, I’m @EmilyEbbaReynolds. And Nando is @NandoDotEternity but “dot” is spelled out. And Nando’s website is NandoAlvarezParez.com.

Scott Ferguson: Great, thanks so much for coming! I hope we can continue this conversation in the future. Thanks.

Nando Alvarez-Perez: Thank you guys. Yes, please.

Emily Ebba Reynolds: It’s been fun.

* Thanks to the Money on the Left production team: William Saas (audio editor), Jakob Feinig (transcription), & Meghan Saas (graphic art)

Primary Document 08262022a by Nando Alvarez-Perez