December 3, 2023 will mark the 200th anniversary of the Monroe Doctrine. It will also mark its obsolescence in the face of popular resistance and the Pink Tide of progressive governments in Latin America that have been elected over the past two and a half decades. The prevailing ideology of these left and left of center movements rejects the “Washington Consensus” and opts for a new consensus based on the decolonization of the political, economic, social and cultural spheres. This consensus is accompanied by encounters and conferences that advance liberatory traditions developed since the 1960’s as well as those deeply rooted in indigenous cultures. It is Washington’s failure to respect and adjust to this political and ideological process of transformation that precludes, at this time, a constructive and cooperative U.S. foreign policy towards the region.

Decoloniality and Multipolarity

One cannot comprehend decolonization from the totalizing point of view of U.S. exceptionalism1. U.S. exceptionalism, the offspring of the African slave trade and the conquest of Amerindia, seeks unfettered access to the region’s natural resources and labor to serve its corporate and geopolitical interests. By contrast, decoloniality was born of five centuries of resistance to colonization. It is the critical perspective of those who have been oppressed by imperial domination and local oligarchies and seek to build a new world, one that rejects necropolitics and racial capitalism; one that advances human life in community and in harmony with the biosphere. This critical ethical attitude has been expressed over the past two years in declarations of regional associations that exclude the U.S. and Canada. All share the same ideal of regional integration based on respect for sovereign equality among nations and guided by ecological, democratic, and plurinational principles.

A necessary condition of integration based on these principles is the freedom to engage economically, politically, and culturally with a multipolar world; it is only in such a geopolitical context that the region can resist subjugation to any superpower and itself become a major player on the world political-economic stage. Such engagement is already a fait accompli. From across the political spectrum, the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC, created in December 2011) has embraced a diversity of trading opportunities. For example, the China-CELAC forum2 was formed on July 17, 2014 as a vehicle for intergovernmental cooperation between the member states of CELAC and China. The forum held its first ministerial meeting3 in Beijing in January 2015, which was followed by two more summits (2018,4 20215), all of which produced economic, infrastructure, energy, and other agreements. Also significant with regard to trade, 20 countries6 in Latin America and the Caribbean have now signed on to the Belt and Road initiative. According to Geopolitical Intelligence Services, GIS:

Chinese trade with Latin America grew from just $12 billion in 2000 to more than $430 billion in 2021, driven by demand for a range of commodities, from soybeans to copper, iron ore, petroleum and other raw materials. These imports, meanwhile, were tied to an increase in Chinese exports of value-added manufactured goods. As of 2022, China is the region’s second-largest trading partner and the biggest trading partner in nine countries (Cuba, Paraguay, Argentina, Chile, Brazil, Uruguay, Peru, Bolivia and Venezuela).7

Moreover, the World Economic Forum predicts that “On the current trajectory, LAC-China trade is expected to exceed $700 billion by 2035, more than twice as much as in 2020.” 8

Rather than acknowledge this trend towards trade diversification, Washington is waging hybrid warfare against Venezuela, Cuba, and Nicaragua, including the use of illegal unilateral coercive measures (“sanctions”), in a bid to limit the influence of Russia, Iran, and China and reimpose its hegemony in the region.

The Special Rapporteur9 of the United Nations on the Negative Impact of Unilateral Coercive Measures on the Enjoyment of Human Rights, Alena Douhan, has visited and documented the effect of the sanctions in Syria,10 Iran,11 and Venezuela,12 and on each occasion has indicated that the sanctions “violate international law” and “the principle of sovereign equality of States,” at the same time that they constitute “intervention in the internal affairs.” As a November 2022 study by the Sanctions Kill Campaign documents, sanctions against Venezuela and other targeted countries have caused devastating hardship and thousands of deaths.13

In order to prevent the import of vital goods to Venezuela, the U.S. went so far as jailing a Venezuelan diplomat, Alex Saab,14 who had managed to circumvent U.S. sanctions to import urgently needed fuel, food, and medicine. In violation of the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations (1961),15 Washington has charged Saab with conspiracy to commit money laundering (other charges having been dropped). A hearing on Saab’s diplomatic immunity was scheduled for December 12, 2022 in Southern District Court. Saab threw a wrench into Washington’s “regime change” machinery, for which he has been paying a heavy price over more than two years.

“Regime change” operations against disobedient governments in Latin America and the Caribbean over the past decade by the U.S. and its right wing allies in the Organization of American States (OAS), has not reduced the influence of China, Iran, and Russia in the region. Just the opposite. For example, while Washington was stepping up its campaign against the government of Cuba, Cuban President Miguel Díaz Canal Bermúdez went to Algeria,16 Russia,17 China,18 and Turkey19 to reinforce mutual solidarity and hammer out new economic accords. Both Russia and China recognize the strategic importance of the Cuban Revolution, for its defeat would have a demoralizing impact on the cause of independence and galvanize oligarchic interests throughout the hemisphere. Moreover, in the context of the Pink Tide of progressive governments, and the disintegration of the Lima Group (a Washington backed right wing coalition) this troika of resistance (Cuba, Venezuela, and Nicaragua) is not alone.

The Pink Tide

It is important not to isolate the period of the Pink Tide as an anomaly, for it has precursors beginning with the first indigenous uprisings and the Bolivarian resistance to Spanish rule. Today’s decolonial struggle is influenced by the spirit of Túpac Amaru, the Hatian revolution, the Sandinista revolution, the Zapatista uprising, and other challenges to conquest, colonization, and the ongoing attempt to recolonize the region.

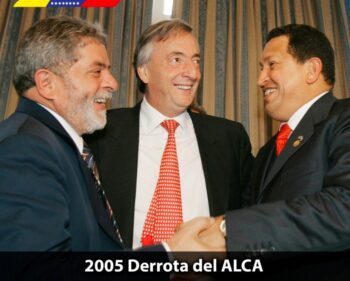

Presidents Lula, Kirchner and Chávez, during the 4th Summit of the Americas in 2005, when the Free Trade Area of the Americas was rejected (credit photo: Twitter account of President Nicolás Maduro)

There is no doubt, however, that the Pink Tide took a big step forward with the election of President Hugo Chávez in Venezuela (1998), Néstor Carlos Kirchner in Argentina (2003), and Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in Brazil (2003). It was perhaps at the Fourth Summit of the Americas, held in November 2005, at Mar del Plata, that their combined bold leadership struck a significant blow to U.S. hegemony by rejecting then President George Bush’s proposal for a hemispheric agreement called the Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA). This defeat of FTAA20 also signaled the determination of progressive movements to seek alternatives to the neoliberal imperatives of the U.S. and Canada.

Although the Pink Tide of progressive governance has suffered some electoral and extra-constitutional setbacks since the Fourth Summit, it has received renewed force with the election of the MORENA party candidate, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) in Mexico in 2018. AMLO ran on a platform that promised to launch the “fourth transformation” of Mexico by fighting corruption and implementing policies that put the poor first. He has since become a major critic of the Monroe Doctrine and the OAS.

The victory of the MORENA movement in Mexico was followed by the election of left and left-of-center presidents in Argentina (Alberto Fernández, October 2019), Bolivia (Luis Arce, October 2020), Peru (Pedro Castillo, July 2021), Chile (Gabriel Boric, December 2021) and Honduras (Xiomara Castro, December 2021). Less than a year later, for the first time in its history, Colombians elected a leftist president, Gustavo Petro, in June 2022. Petro wasted no time in re-establishing diplomatic relations with Venezuela and opening their common border. This South American nation, however, still remains host to nine U.S. military bases and remains a partner of NATO. This historic win was followed by a momentous comeback of the left in Brazil with the election of former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in October 2022 after the extreme right wing rule of Jair Bolsonaro. This is big news, as Brazil is not only a major economic power in the hemisphere, but a member of the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) association, which is now expected to increase commerce and integrate a growing number of member states.

Regional associations seize the moment

These electoral victories, all of which relied heavily on the support of the popular sectors, have been the subject of critical analysis at several recent meetings of regional associations. These meetings express the formation of a consensus on advancing regional sovereignty, protecting the environment, respecting indigenous peoples’ rights, and attaining social justice.

The spirit of independence and regional integration was given new impetus when AMLO assumed the pro tempore presidency of CELAC in 2020. The last CELAC Summit21 set the basic tone for this consensus when on July 24, 2021, AMLO evoked the legacy of Simón Bolívar in the context of the ongoing cause of regional independence; this focus opened a political space for criticizing the OAS and fortifying CELAC. The Summit was held at a time of widespread condemnation of the OAS’ role in provoking a coup in Bolivia.

The message of the CELAC summit had apparently not made much of an impression in Washington. The Ninth Summit of the Americas,22 hosted by the United States in Los Angeles, California (June 2022), excluded countries on Washington’s “regime change” list, revealing a profound disconnect between U.S. hemispheric policy and the reality on the ground in Latin America. This exclusivity inspired alternative, more inclusive summits: the People’s Summit in Los Angeles23 and the Workers’ Summit in Tijuana.24 These alternative summits exposed Washington’s failure to adjust to increasingly independent neighbors to the South. To avoid embarrassment however, Washington did not invite self-proclaimed president of Venezuela, Juan Guaidó, though it now stands virtually alone in pretending to recognize this comic figure and his inconsequential, corrupt shadow government.

Mapuche protest in Chile, using signs in their language, defending their right to cultural independence and land recovery (credit photo: Pressenza International News Agency, https://www.pressenza.com/)

Five months after the divisive Summit of the Americas, there was a meeting of the Puebla Group which was founded in July 2019 to counter the right wing agenda of the Washington-backed Lima Group. It held its eighth meeting in the Colombian city of Santa Marta. On November 11th, the Group issued the Declaration of Santa Marta: The Region United for Change.25 It declared that “the region needs to incorporate and emphasize new themes for the regional agenda that in the past, for different reasons, did not have the visibility that today appears indisputable, such as . . . gender equality, the free movement of people, the ecological transition, the defense of the Amazon and of the rights of indigenous peoples, . . . and the necessity to include new social and economic actors in the regional processes of integration.”

Just a few days later, in a letter dated November 14, a group of regional leaders called upon South America’s presidents 26 to reconstitute the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR, created in 2008). The disintegration of UNASUR was a reflection of an offensive against the Bolivarian revolution, led by Washington and Bogota. When Colombia left the organization in 2018, with its right wing allies to follow, it then joined the Lima Group, whose only political goal within the OAS was the destruction of the Bolivarian cause. And in August 2018 after President of Ecuador Lenin Moreno confiscated the UNASUR headquarters in Quito, President Evo Morales reopened the UNASUR headquarters in Bolivia. Morales declared, “The South American Parliament [UNASUR] is the center of integration and the symbol of the liberation of Latin America. The integration of all of Latin America is a path without return.” At that moment, the only country allied with Venezuela in South America was Bolivia.

The letter calling for the reconstitution of UNASUR was followed by a statement by the São Paulo27 Forum, which met in Caracas November 18—19, 2022 and summed up one of the principal themes of the present juncture:

We are in a historic moment for resuming and deepening the transformations in the economic and geopolitical fields that have occurred since the beginning of the century, and for accelerating the transition to a democratic multipolar world, one based on new international relations of cooperation and solidarity.

On November 22—25, in Guatemala, representatives of indigenous peoples from 16 countries came together for the second meeting of the Sovereign Abya Yala movement. The conference took place at a time of renewed political protagonism of indigenous peoples throughout the continent. For example, after the fascist coup in Bolivia in November 2019, it was the fierce resistance of indigenous peoples and the Movement toward Socialism IPSP that led to the successful recuperation of democracy one year later. The theme of the second meeting was “Peoples and communities in movement, advancing toward decoloniality in order to live well (“Buen vivir”).” Its final declaration commits to the decolonization of these territories. To accomplish this, the meeting proposed pluri-nationality as a guiding political principle, “to construct new plurinational states, new laws, institutions, and life projects that make it possible for all beings sharing the cosmic community to live together in harmony.” The declaration also recognizes the need to form political organizations that can advance these goals, including in the electoral field.28

There is now a solid bloc of progressive governments in the region, presenting new opportunities to advance the causes of decolonization, integration, resource nationalism, popular sovereignty, and experiments in building a post-neoliberal order. But this juncture also poses new challenges. The U.S. recent partial lifting of sanctions against Venezuela in the oil sector and support for negotiations in Mexico between the Venezuelan government and opposition is a pragmatic response to the need to access Venezuelan crude and signals a shift in U.S. tactics to an electoral means to bring about “regime change”. This is reminiscent of the U.S. strategy in Nicaragua in the late 1980’s which led to the Sandinista electoral defeat of 1990. The U.S. is also acting with restraint because given the heightened geopolitical tensions over the war in Ukraine and the political climate in this hemisphere no other path is feasible. Washington continues, however, to pursue illegal unilateral coercive measures against Venezuela, Nicaragua, and Cuba in a ploy to keep the obsolete Monroe Doctrine alive. To meet this challenge to their existence, the targeted governments are circumventing U.S. sanctions, resisting “regime change” operations, resuming efforts at integration, deepening ties to Russia and China, and diversifying their trade partners. And while hard-liners in the U.S. Congress, stuck in a cold war mentality, are scouring the hills for communists, all of Amerindia is working to end the last vestiges of armed conflict and establish a region at peace.

William Camacaro is a Senior Analyst at COHA. Frederick Mills is Deputy Director of COHA

All translations from Spanish to English by the authors are unofficial. COHA Assistant Editor/Translator Jill Clark-Gollub provided editorial assistance for this article.

Sources

- ↩ Based on Donald E. Pease definition, “American exceptionalism has been taken to mean that America is either ‘distinctive’ (meaning merely different), or ‘unique’ (meaning anomalous), or ‘exemplary’ (meaning a model for other nations to follow), or ‘exempt’ from the laws of historical progress (meaning that it is an ‘exception’ to the laws and rules governing the development of other nations).” American Exceptionalism, www.oxfordbibliographies.com

- ↩ “Basic Information about CELAC-China Forum,” Department of Latin American and Caribbean Affairs, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of China. April 2016. Accessed Dec. 3, 2022: www.chinacelacforum.org

- ↩ “Relevant Sub- Forums under China-CELAC Forum in 2015.” China-CELAC Forum, News. Feb. 17, 2016. Accessed Dec. 3, 2022: www.chinacelacforum.org

- ↩ Second Ministerial Meeting of China—CELAC Forum. United Nations (ECLAC). Jan. 22, 2018. Accessed Dec. 3, 2022: www.cepal.org

- ↩ Declaration of the Third Ministers’ Meeting of the China-CELAC Forum. China-CELAC Forum, Important Documents. December 9, 202. Accessed Dec. 3, 2022: www.chinacelacforum.org

- ↩ Countries of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Green finance and development center. Based on information as of March 2022. Accessed Dec. 3, 2022: greenfdc.org

- ↩ “China’s evolving economic footprint in Latin America,” by John Polga-Hecimovich. Geopolitical Intelligence Services. Economy. November 22, 2022. Access Dec. 3, 2022: www.gisreportsonline.com

- ↩ “China’s trade with Latin America is bound to keep growing. Here’s why that matters.” World Economic Forum. June 17, 2021. Accessed Dec. 3, 2022: www.weforum.org

- ↩ Special Rapporteur on the Negative Impact of Unilateral Coercive Measures Says Guiding Principles Need to Be Drafted to Protect the Rights and Lives of People. United Nations, Human Rights, Office of the High Commissioner. September 14, 2022. Accessed December 3, 2022: www.ohchr.org

- ↩ “Lift ‘suffocating’ unilateral sanctions against Syrians, urges UN human rights expert.” United Nations. UN News. November 10. 2022. Accessed Dec. 3, 2022.

- ↩ “Iran: Unilateral sanctions and overcompliance constitute serious threat to human rights and dignity—UN expert.” United Nations, Human Rights, Office of the High Commissioner. May 19, 2022. Accessed Dec. 3, 2022: www.ohchr.org

- ↩ “Preliminary findings of the visit to the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela by the Special Rapporteur on the negative impact of unilateral coercive measures on the enjoyment of human rights.” United Nations, Human Rights, Office of the High Commissioner. February 12, 2021. Accessed December 3, 2022: www.ohchr.org

- ↩ “U.S. Sanctions: Deadly, Destructive and in Violation of International Law.” Report produced by Rick Sterling, John Philpot, and David Paul with support from other members of the SanctionsKill Campaign and many individuals from sanctioned countries. November 2022 (Updates of previous publications in September 2020 and May 2021). Accessed Dec. 5, 2022: sanctionskill.org

- ↩ “The U.S. flies Alex Saab out from Cabo Verde without court order or extradition treaty,” by Dan Kovalik. Council on Hemispheric Affairs. October 18, 2021. Accessed December 3, 2022: www.coha.org

- ↩ Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations, 1961. United National. Accessed December 3, 2022: legal.un.org

- ↩ “Díaz-Canel Arrives in Algiers, 1st Stop on Presidential Tour.” Telesur. November 16, 2022. Accessed December 3, 2022: www.telesurenglish.net

- ↩ “Díaz-Canel en la reunión con Putin: ‘El mundo tiene que despertar’.” RT. November 22, 2022. Accessed December 3, 2022: actualidad.rt.com

- ↩ “El Secretario General y Presidente Xi Jinping Sostiene una Conversación con el Primer Secretario del Comité Central del Partido Comunista de Cuba y Presidente de la República de Cuba Miguel Díaz-Canel.” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. November 25, 2022. Accessed December 3, 2022: www.fmprc.gov.cn

- ↩ “Turkey, Cuba to bolster bilateral ties.” La Prensa Latina: Bilingual Media. November 23, 2022. Accessed December 3, 2022: www.laprensalatina.com

- ↩ “América Latina celebra 13 años de la derrota del ALCA”. Telesur. November 4, 2018. Accessed Dec. 3, 2022. www.telesurtv.net

- ↩ “Cumbre CELAC 2021: renovada apuesta por la integración latinoamericana”. Silvina Romano y Tamara Lajtman. Celag.org. 18 Septiembre, 2021. Accessed Dec. 3, 2022: www.celag.org

- ↩ Summit of the Americas. U.S. Department of State. Accessed Dec. 3, 2022: www.state.gov

- ↩ People’s Summit. June 8, 2021. Code Pink. Accessed Dec. 3, 2022: www.codepink.org

- ↩ Worker’s Summit of the Americas. June 10—12. Accessed Dec. 3, 2022: workerssummit.com

- ↩ Declaración de Santa Marta: “La Región, Unida por El Cambio”, November 2022. Grupo de Puebla. Resumen Ejecutivo. November 11, 2022. Accessed Dec. 3, 2022: www.grupodepuebla.org

- ↩ Alberto Fernández, Luis Arce, Luiz Inacio “Lula” da Silva, Guillermo Lasso, Gabriel Boric, Gustavo Petro, Irfaan Ali, Mario Abdo Benítealista

- ↩ “Declaración del Foro de São Paulo”. Reunión ampliada del Grupo de Trabajo Caracas, 18 y 19 de noviembre de 2022. Accessed December 5, 2022: forodesaopaulo.org

- ↩ “Declaración del II Encuentro de Abya Yala Soberana”. Abya Yala Soberana. November 30, 2022. Accessed Dec. 4, 2022: abyayalasoberana.org