Hank Kennedy revisits the film classic High Noon and finds its commentary on the Hollywood blacklist contains lessons for today.

The film High Noon, written by Carl Foreman, produced by Stanley Kramer, and directed by Fred Zinneman, turned 70 this past year and is considered one of the finest western films of all time. The catchy, Tex Ritter-sung theme song is included on the American Film Institute’s list of 100 most significant American movie songs and the Western Writers of America’s list of 100 best western songs. The 1952 film was nominated for seven Academy Awards, winning four for Best Actor, Best Editing, Best Original Song, and Best Score and winning the WGA award for Best Screenplay. High Noon is listed second on the AFI’s list of top ten westerns. In the years following the film’s release, it became a favorite of U.S. Presidents Eisenhower, Reagan, and Clinton, who reportedly screened the film seventeen times in the White House. However, despite this current unanimous acclaim, the story of High Noon is inseparable from one of the most trying times for the U.S. Left.

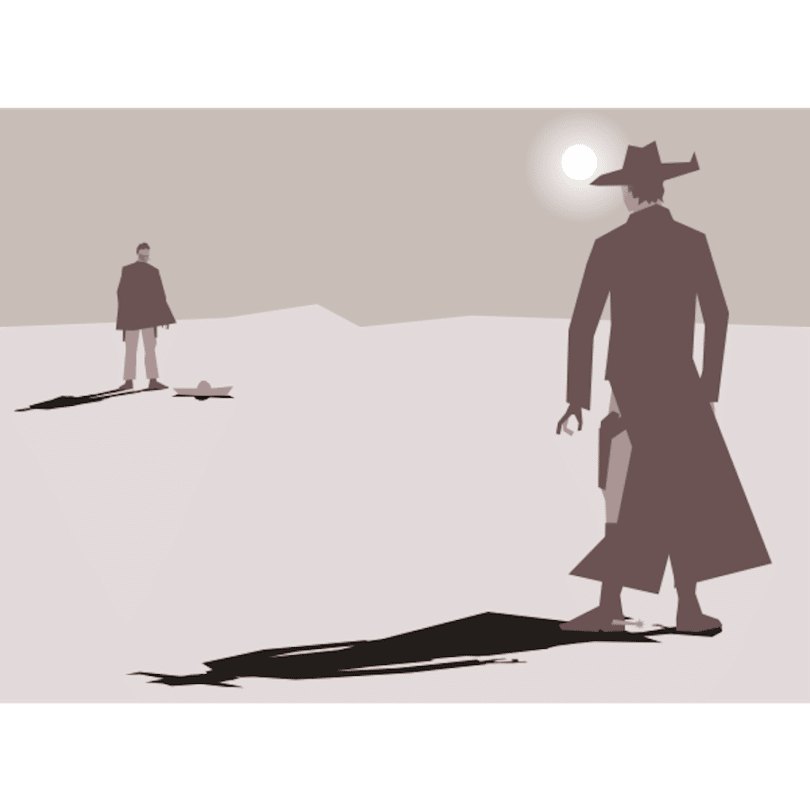

On its surface, High Noon tells a pared-down, archetypal western story. Will Kane (Gary Cooper), is a town marshall in the town of Hadleyville, set to retire with his Quaker bride Amy (Grace Kelly). However, before Will and Amy can leave they receive word that Frank Miller, a vicious killer Will put away five years prior, has been pardoned and is on his way to Hadleyville. Will vows to stay and defend the town from Miller and his gang, while also attempting to find deputies who will help him in the fight.

Unfortunately for Kane, his pleas are rebuffed by virtually everyone in town, for a variety of reasons. The Justice of the Peace is scared of Miller, the old marshall is arthritic and can’t hold a pistol, and the current deputy resents Kane because he was turned down for a promotion. The film’s climactic scene is not the gunfight, but a church service, when Will interrupts to appeal to Hadleyville’s solidarity. At first, everyone is with Will but this dynamic quickly turns,what finally sways everyone is an appeal to their economic self-interests: Northern financiers are looking to invest in Hadleyville and a gunfight on the streets will deter their investments. Kane will have to face Miller’s gang alone. Even Amy has turned her back on Will, as violence conflicts with her Quaker beliefs.

In the exciting gunfight that follows, Will triumphs over the killers, with Amy’s assistance after she realizes that pacifism is not a practical policy. When Amy and Will leave the town, he throws his marshal star in the dust to show his disdain for Hadleyville’s cowardice.

High Noon was written by screenwriter Carl Foreman, who would become a victim of Hollywood’s anti-Communist blacklist. Even though Foreman had left the Communist Party by the time of his questioning by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), he refused to name names before the committee as a matter of principle. This led to the dissolution of his partnership with producer Stanley Kramer, who felt that working with Foreman would be bad for his career. Kramer would find success as the director of “message movies” like Judgement at Nuremberg and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner. As a result of Foreman’s refusal to name names, he was considered an “uncooperative witness” and was blacklisted by all of Hollywood’s major studios.

Foreman intended Hadleyville to stand in for Hollywood, with Miller standing in for HUAC, saying:

There are scenes in the film that are taken from life. The scene in the church is a distillation of meetings I had…And there’s the scene with the man who offers to help and comes back with his gun and asks, where are the others? Cooper says there are no others… I became the Gary Cooper character.

Foreman was not the only member of the film’s cast and crew to experience problems as a result of HUAC. Howland Chamberlain, who plays the hotel desk clerk would not appear in another film until more than twenty-five years later, in 1979’s Kramer vs. Kramer, as a result of his blacklisting. Lloyd Bridges was blacklisted briefly due to his membership in the Actor’s Laboratory Theater until he agreed to cooperate with HUAC. Actress Virginia Farmer, who played Mrs. Lewis, was blacklisted and never worked again after the film. Floyd Crosby, the film’s cinematographer, found it difficult to get mainstream work despite his acclaimed work on High Noon and Crosby spent most of the rest of his career working on B-movies (low-budget films) like Attack of the Crab Monsters and the Screaming Skull.

Gary Cooper was an odd choice to star in a left-wing message film, despite being the subject of a bizarre FBI investigation over a pro-communist speech he was said to have given. Actors with more progressive political leanings like Henry Fonda and Gregory Peck had turned down the role of Will Kane. Cooper had strongly opposed Franklin Roosevelt in both the 1940 and 1944 elections, even paying for a 1944 radio broadcast in which he assailed the New Deal for borrowing “foreign notions.” Cooper was a friendly witness at a 1947 HUAC committee meeting where he stated that he turned down roles in films “tinged with communist ideas.” He was also a member (along with the likes of Walt Disney, Ronald Reagan, and John Wayne), of the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals (MPA) which was an organization dedicated to rooting out perceived communist infiltration in Hollywood. Despite this, Cooper was an opponent of blacklisting and gave Carl Foreman words of support when the screenwriter had to testify before HUAC as an “unfriendly witness.”

The Left did not know what to make of High Noon. The International Socialist League was split. In a November 24, 1952 review in Labor Action, reviewer Hal Draper (under the pen name Phillip Coben) defends the film against charges that it is “anti-democratic” but also states “it is doubtful that High Noon was made with as conscious a social message” as other Hollywood movies. Draper found the film to be a robust defense of individual integrity and determination. However, in a letter written for the December 8, 1952 edition of Labor Action, the writer, Bob Bone, condemned the movie as “insidious war propaganda.” The April 26, 1952 review of the film in the Nation called High Noon a “perfectly fouled up western,” without commenting on the political subtext. The Communist Party USA’s Daily Worker stated the movie displayed “the usual amount of cynicism and misanthropy. The high point of the film, with Gary Cooper stalking down the street in intense loneliness, is a classic restatement of the anti-human theme of nearly all cowboy and detective yarns.” The Soviet Union’s Pravda opined that High Noon was a film “in which the idea of the insignificance of the people and masses and grandeur of the individual found its complete incarnation.” The New York-based Partisan Review mocked this view by saying “A hundred years after the Manifesto, the specter haunting Europe is-Gary Cooper!” Film critic Bosley Crowther of the New York Times did get the intended message, writing that the courage of Will Kane “could give a fine lesson to the people in Hollywood today.”

Despite the failure of most of the Left and liberal press to see it, the allegory in High Noon is actually fairly obvious. Will Kane’s earlier defeat of Miller is a reflection of anti-fascist activism in Hollywood through things like propaganda films and fundraisers. In his book Gunfighter Nation, Richard Slotkin writes,

Miller’s return is a metaphorical way of identifying McCarthyism with Fascism: the same people who in an earlier and less prosperous time had risen up to defeat the enemy have now grown too comfortable or complacent to risk their lives and fortunes for the public good.

The townsfolk who refuse to fight are representative of Hollywood liberals like Edward G. Robinson and Humphrey Bogart who turned their backs on the victims of the blacklist. The film also attacks the institutions of organized religion and big business as being unwilling and unable to stand up to the resurgence of fascism. In the film’s famous church debate, support for economic growth and “progress” are arguments used against standing up to the villains. Katy Jurado’s saloon owner Helen Ramirez is also an important part of this allegory. Ramirez experiences racism on the part of the town and owns her business as a silent partner with a white man who is the official owner. She also flees Hadleyville due to Miller’s return, a sign of the persistence of racism despite the defeat of fascism.

The Right, however, latched onto High Noon’s intentions immediately. The American Legion Magazine singled out the movie for derision since its cast and crew included “Communist-collaborators.” The review in the Hollywood Citizen-News claimed that “the weakness of the ‘good citizens’ of the town, which are underlined repeatedly are just the kind of thing which brings forth cries of communist propaganda in motion pictures.” MPA President John Wayne led a campaign against the film and Gary Cooper’s business partnership with Carl Foreman. Wayne even went to Foreman’s house and threatened him in order to convince the screenwriter to return to HUAC and name names. Foreman instead left the country and found work in the U.K. on films like The Bridge on the River Kwai and the Guns of Navarone. Years later, John Wayne maintained his hatred for the film calling it “the most un-American thing I’ve ever seen.” This was in the same 1971 Playboy interview in which he stated his support for white supremacy. Wayne maintained that he’d “never regret having helped run Foreman out of the country.” There was also a concerted campaign against High Noon in the lead-up to the Academy Awards. Luigi Luraschi, an executive at Paramount, Academy member, and Central Intelligence Agency asset, wrote a letter to his contact taking credit for ensuring that High Noon lost the award for Best Picture. Perhaps not coincidentally, the winner that year was the Greatest Show on Earth, directed by MPA member, blacklist supporter, and staunch anti-communist Cecil B. DeMille.

Seventy years later, the question is how we on the Left should remember High Noon. The Left of the past did not like the film because they felt it was anti-democratic to depict the forces of good in the minority. But unfortunately, sometimes we fighters for democracy, equality, and socialism do find ourselves in the minority. The voices against segregation, the War in Vietnam, and homophobia once found themselves in the minority also, but they fought on regardless. We should carry on in that spirit as we fight our battles for a better world, and as we return to the cinema.