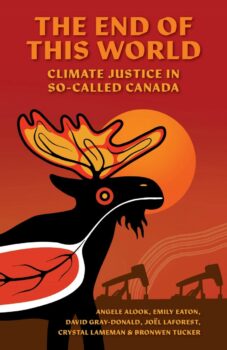

The following is an excerpt from The End of This World: Climate Justice in So-Called Canada by Angele Alook, Emily Eaton, David Gray-Donald, Joël Laforest, Crystal Lameman and Bronwen Tucker, released this year by Between the Lines. For more information, visit www.btlbooks.com.

In 2009, the oil sands (or tarsands) company Nexen gave funding to the Canadian Defence and Foreign Affairs Institute (CDFAI) to prepare a now-forgotten study called Resource Industries and Security Issues in Northern Alberta. The institute hired Tom Flanagan, a conservative academic often called “the man behind Stephen Harper,” to write it. Flanagan warned of a possible “apocalyptic scenario” if there were ever prolonged and deep collaboration between environmentalists, First Nations, and the Métis people, among other groups. By “apocalyptic,” he meant that industries like oil and gas would have trouble continuing to extract resources and profits in northern Alberta and would no longer be able to flagrantly disregard Indigenous rights. If these groups were to “make common cause and cooperate with each other,” Flanagan wrote, they could form “a coordinated movement with the ability to block resource development on a large scale.”

The End of This World: Climate Justice in So-Called Canada by Angele Alook, Emily Eaton, David Gray-Donald, Joël Laforest, Crystal Lameman and Bronwen Tucker, released this year by Between the Lines. For more information, visit www.btlbooks.com.

A lot has changed since then—the think tank CDFAI has been rebranded as the more benign-sounding Canadian Global Affairs Institute, Nexen no longer exists after being bought out by CNOOC Ltd., and Flanagan has largely fallen out of the public eye—but we think his central point is more relevant than ever. In fact, it’s a big part of why we wanted to write this book. Except, from our perspective, “a coordinated movement” between Indigenous peoples, settler environmentalists, organized labour, and many others is the precise opposite of an apocalyptic scenario. We think it’s the one thing that could bring us back from our current slide into climate collapse, colonial genocide, and extreme inequality, and towards a better world where we live in balance with land and life.

But this is, of course, much easier said than done. Flanagan predicted that deep and sustained collaboration between groups was unlikely because they wouldn’t be able to overcome their different interests and mount a sufficiently large-scale challenge to the fossil fuel and colonial power structures in so-called Canada. Despite recent inspiring moments of solidarity—from Idle No More, to Québec and east coast coalitions to stop Energy East and Alton Gas, to cross-country Wet’suwet’en solidarity blockades to stop the Coastal GasLink pipeline—Flanagan has, unfortunately, largely been correct on this point. And since he wrote the report in 2009, the stakes have become so much higher. As we write in the early 2020s, the COVID-19 pandemic has facilitated a growth in wealth estimated at $78 billion for the 47 billionaires in Canada while 5.5 million Canadian workers have been thrown out of their jobs, the oil and gas industry is securing plans to expand its production this decade more than any country other than the United States, and chronic underfunding and resource development without consent continue to undermine Indigenous sovereignty.

One reason a sufficiently powerful and coordinated movement hasn’t emerged to counter these threats is the targeted efforts from politicians and the oil and gas industry to stop one from emerging. Flanagan himself was actively working to prevent Indigenous solidarity movements, despite dismissing them as unlikely to emerge in the CDFAI report; while he was writing it, he was also working on a book on “how to voluntarily introduce private property rights onto First Nations lands in Canada.” Flanagan’s proposal, which would extinguish collective Indigenous land rights, found industry backers keen on stopping Indigenous rights from impeding resource development. Meanwhile Harper’s Conservative federal government introduced further measures to impede Indigenous and cross-movement resistance to resource extraction, with legislation that criminalized land defence and allowed surveillance of movements by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) and Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS). And in 2012 Harper introduced an omnibus bill that undermined Indigenous land rights and removed protections for the environment. In the words of Mi’kmaw lawyer Pamela Palmater, resistance was undermined by the government making “conditions so unbearable on reserves that First Nations are forced to leave their communities and give up their lands for resource extraction.”

Though later federal Liberal and provincial New Democratic Party governments have used much softer-sounding language, their strategies have been largely the same. Successive governments at both levels talk about “reconciliation,” “consultation,” and “partnership” with the original peoples of these lands, yet First Nations continue to be subject to boil water advisories, Indigenous children’s health and education programs continue to be underfunded compared with those of settler children, companies continue to extract on lands that they have no consent to be on, and the Canadian state continues to undermine Indigenous sovereignty at nearly every turn.

But beyond governments’ efforts to maintain the status quo, a key reason cross-movement collaboration has been limited is that potential allies have not managed to go much beyond a narrow common cause—saying no to harmful resource development. To transform away from economies built on destruction and death, we need to say yes to much more together. We need a shared vision for a future that is just: where Indigenous and other rights are respected, where everyone has their basic needs met, and where our economies operate in a respectful relationship with nature. In this book, we call this a just transition.

We are a group of six authors who have been working to build this future. Each of us on the author team came to this work in a different way, and we think that together our experiences and the lessons we have learned from our elders and others have taught us what a just future could look like, what stands in the way, and some pathways for how to get there together. This is the vision we hope to share.

Through our diverse work and experiences at the intersection of Indigenous rights and climate justice, we’ve noticed that while these movements are getting closer, we do not yet mount the critical threat to business as usual that Flanagan identified. Something holding us back has been that settler-led climate discussion in Canada—including in reports, books, mainstream media, and at environmental NGOs—has been treating Indigenous rights as an afterthought. When Indigenous rights are mentioned at all, they appear as an add-on, in a separate chapter, under their own subheading, or in special reporting focusing specifically on how climate justice relates to Indigenous peoples. In this book, we want to challenge this practice by putting Indigenous rights and sovereignty at the centre of what needs to be done to rescue a habitable planet. We cannot repair our relationship to the environment without also acknowledging and restoring our relationships to one another.

Canada’s fossil fuel industry is powerful and organized. It wields tremendous influence over our political, social, and cultural institutions, a theme thoroughly explored in William Carroll’s book Regime of Obstruction: How Corporate Power Blocks Energy Democracy. But the fact is that Canada’s extractive economy only exists in these lands because of a long history of false promises in which the Crown (representatives of the British monarchy, Canada’s official head of state) swore Indigenous peoples would maintain their inherent rights and only benefit from the incoming settler societies. From the start, and continuing until today, instead of working within this framework of mutual benefit and respect, so-called Canada has been stealing Indigenous lands and resources and handing them over to fossil fuel corporations to make relatively few people very wealthy.

More and more settlers are coming to realize that an ongoing theft and denial of Indigenous rights is happening here. And this brings up big feelings. Indigenous peoples, who have long known and lived this reality, continue to face systems of colonial control today, despite royal commissions, apologies, and new rounds of promises from successive governments to get things right. And for settlers relatively newly confronted with this reality, the realization can bring a sense of unease and uncertainty. For some, it has prompted a backlash—and an even more fervent assertion of Canada’s supremacy and control over Indigenous Nations, peoples, and lands. But it doesn’t need to be this way. In this book we acknowledge the ongoing reality of land theft and oppression and offer a vision of how we might begin to undo it. We encourage you to work with us to build a new world, one where Indigenous sovereignty is fully recognized and we live in good relations with each other and the earth.

In brief, we are calling for mass movements, grounded in shared demands for Indigenous sovereignty, that can make big, positive changes happen. Climate action in so-called Canada can’t be considered separate from Indigenous rights. In fact, asserting Indigenous sovereignty will require putting limits on the capitalist economy of Canada that has been wreaking so much havoc. Attempting an energy transition without asserting Indigenous rights is simply greening theft—and it is also doomed to fail. Indigenous knowledges and cultures have invaluable lessons for how to live on these lands, knowledges that we need to move from economies of destruction to economies that repair lands and life. We can diminish the power of the fossil fuel industry and move to renewable energies, while reducing inefficient and wasteful uses of energy. We can enjoy comfortable, safe, reliable low-emissions public transit and buildings in both rural and urban areas. Cities and towns can provide great social services like healthcare and education, and can be far less car-dependent. The gaps between rich and poor can be rapidly closed so we can all live better and with a heightened sense of belonging and trust. Far from being unattainable, these changes are already happening, though not fast enough. And joining in social movements pushing for these changes has the added benefit that, instead of being stuck in feelings of despair and isolation, you can participate in hopeful, creative, and engaging communities.

We believe it is important for just transition discussions to be accessible to all audiences because, fundamentally, what we are talking about in this book is repairing relationships. Repairing relationships with each other and with the land. And key to any relationship is to listen deeply to each other. With that in mind, we invite you to read this book with an open heart and mind.