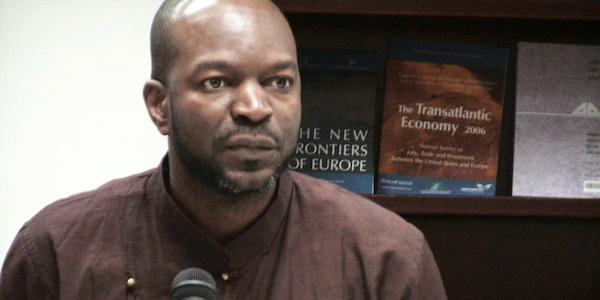

Maurice CarneyJanine Jackson interviewed Friends of the Congo’s Maurice Carney about the assassination of Patrice Lumumba for the January 20, 2023, episode of CounterSpin. This is a lightly edited transcript.

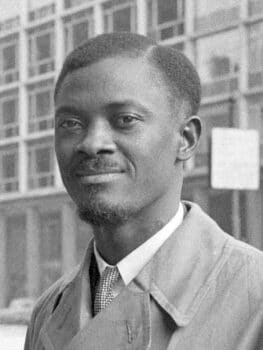

Patrice Lumumba

Janine Jackson: CounterSpin listeners will have heard a number of tributes to Martin Luther King Jr. this past week—a few searching, many shallow. Importantly, the King holiday usually includes attention to his assassination, as well as to his life and work, though even the best reports, if we’re talking about corporate media, fail to draw the straightest lines between the two.

This week also marks the anniversary of another assassination, that of Patrice Lumumba, the first elected prime minister of the post-independence Democratic Republic of the Congo. Elite media appear to find that 1961 murder harder to pave over, and easier to just ignore.

But thinking about it, learning about it, involves the same sort of challenges to the U.S. role in the world, and how racism shapes that role—lessons that we very obviously still need to learn.

We’re joined now by Maurice Carney, co-founder and executive director of the group Friends of the Congo. He joins us by phone from Washington, DC. Welcome back to CounterSpin, Maurice Carney.

Maurice Carney: Thank you. Thank you, Janine. It’s my pleasure to be back with you.

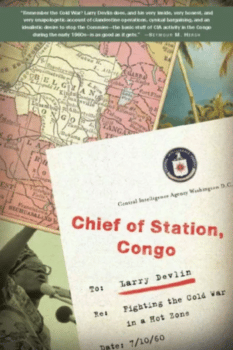

(PublicAffairs, 2008)

JJ: I will ask you to begin where we have in the past, with a reminder to listeners about January, 1961, and the circumstances of Patrice Lumumba’s assassination. How was the U.S. involved, but also why was the U.S. involved?

MC: Yes, the United States was directly involved. In fact, Janine, the United States State Department released declassified documents a number of years ago, in the last seven years or so, and those declassified documents revealed that the operation in the Congo on the part of the United States and its Central Intelligence Agency, the covert operation, was the largest in the world at that time, in terms of financing.

And the chief of station, Larry Devlin, chief of station of the CIA in the Congo, he wrote a book entitled Chief of Station, Congo, and he laid out why that the United States felt that Congo was important, and that it remained in the sphere of influence of the United States.

Larry Devlin said, in essence, that if we did not overthrow Lumumba, not only would we have lost the Congo, we would’ve lost all of Africa.

So Devlin centered the Congo as a part of U.S. overall foreign policy, strategic policy for the African continent. So the overthrow of Lumumba was vital to the United States.

And we say “overthrow” because, in Devlin’s book, it’s really a playbook that he lays out for how the United States moves against democratically elected leaders who are not necessarily inclined to toe Washington’s line.

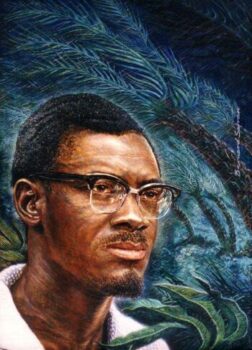

A painting of Patrice Lumumba by Bernard Safran, commissioned by Time magazine but not published.

And that was the problem that the United States had with Lumumba, that he was an African nationalist and a pan-Africanist, one who loved his people, loved the continent, and, as Malcolm X stated, he was the greatest African leader to ever walk the African continent.

And the reason why Malcolm X said that is because he saw that the U.S. couldn’t reach Lumumba, in the sense that they couldn’t corrupt him, they couldn’t entice him to sell out his people for trinkets, just like some of the other Congolese leaders had done.

So the Congo was key, and it’s key for a whole host of reasons that we can share a little later.

JJ: And the idea that the CIA chief of station, Larry Devlin, would use the pronoun “we”—”we” might lose Africa. This is so deeply meaningful in terms of policy narrative, and here’s where media come in to play their role of serving this narrative.

And I know that you’ve spoken in the past about the role that U.S. news media played in working with the CIA and Larry Devlin and other U.S. foreign policymakers to destabilize Congo and Lumumba. Media storytelling carried a lot of weight here.

MC: Absolutely, absolutely. The narrative is critical. It was a number of years ago we talked about, Time magazine at the time was portraying Lumumba as a monster, basically laying the groundwork to justify his liquidation and removal from power.

NPR (12/20/22)

We paint this picture of a monster to the global media when covert action is actually implemented by the Central Intelligence Agency, the U.S. government, then folks are going to say, well, oh, he was a monster anyway. So it doesn’t matter if he was democratically elected. Doesn’t matter if he was a legitimate prime minister. He was a bad guy.

And the United States and its media and its people see themselves as the good guy. So if the good guys move in and get rid of the bad guys, then it’s fine.

And this is really an important point, too, Janine, because that narrative, these people who were involved at the time, some of them are really still alive today. They write books and they make films to paint themselves in a positive light, because of their concern of the repercussion of history, when the truth actually comes out, in terms of the dastardly role that they played, in not only removing a democratically elected leader who was subsequently assassinated, but also imposing a dictatorship over the Congolese people, in essence destroying any prospect of a peaceful, democratic, prosperous country in the heart of the richest continent on the planet.

So recounting the story and correcting the history and continuing to tell the story, especially during the commemoration of Lumumba’s assassination, is so vital. It’s so critical, and it’s not something that is stuck in the past, but it’s very, very much relevant for today, because the same forces that were at play in the ’60s to remove Lumumba are at play today in terms of keeping the Congolese from advancing and fully benefiting from the enormous wealth that’s in their country, which is what Lumumba stood for.

CNN (9/10/22)

He made it clear, in no uncertain terms, that he was going to serve the interest of the Congolese people. He was going to leverage the wealth of the Congo, not only for the benefit of the Congo, but for Africa as a whole.

This basically scared the Western powers, because they thought they were going to lose access to the resources that we’ve learned, over the decades, are vital to a whole range of industries—not only in the West, but global industries.

JJ: This is absolutely a story about this very day today, and it’s so important to not think of this as a historical commemoration. But when I looked for coverage, I found pretty much nothing in terms of U.S. media coverage.

But I did find, for example, when I was just looking for references to Lumumba, one of the things I found was the Dutch prime minister’s official apology for that country’s role in slavery and in the trading of enslaved people.

And I wanted to ask the role of these official statements, about apologies, which is not the same thing as a truth and reconciliation conversation, but these official apologies in the context of a general informational void about the specific actions and attitudes that created the phenomenon that now official people are sad about.

And with context to Congo, I just wonder: This is the coverage, this is what media covers, is when a powerful person says I’m officially sorry, and that’s not the kind of coverage we need.

Maurice Carney: “The same forces that were at play in the ’60s to remove Lumumba are at play today in terms of keeping the Congolese from advancing.”

MC: Right. And that’s in line with narratives over the past few years, right? Because, see, even the summer of 2022, you have the Belgian king, who had gone back to Congo. He didn’t apologize for the role that Belgium played in basically plundering and destroying the Congo. But he said he regretted it.

And this apology, regret, it’s really important, because remember, one of the events that shot Lumumba into world attention was his June 30, 1960, inauguration speech, where he laid out in excoriating detail the nature and the scope of the brutality of King Leopold II in the Congo and Belgian colonialism.

So we are talking about some 60 years later, where you have the Dutch or the Belgians issuing apologies or regrets, it really doesn’t carry weight for the masses of Africans. And I say that because, if you recall the passing of the queen of England, and if you look at the coverage, you saw that Africans writ large were basically celebrating, and recounting in detail the atrocities that the British colonial power carried out, not only in Africa, but certainly in India and in Asia.

So this apology narrative, Janine, it’s really an elite affair. And the broadcasting of it is sharing the crocodile tears of elites. But if you consult the masses, if you look at the oppressed masses, the working class, you’ll find the type of response that they have, not only to colonialism, but also to neo-colonialism and contemporary capitalists and imperialist exploitation of their lands.

And you’ll find outrage, you’ll find anger, and you’ll find people teeming to demand change of the power relations that exist currently in the world today.

JJ: I know that Friends of the Congo works year round, but that you also use every January 17 to uplift the life and the murder and the legacy of Patrice Lumumba, as well as that of Joseph Okito and Maurice Mpolo, who also died on that day.

And I would like you to talk a little bit about the goals of the action that you do every year, because it’s not just lamentation; it’s about more.

MC: Exactly. Exactly. We commemorate Lumumba to remind the world, not only of the imbalance in the power dynamics between the Western world and the global South, but also to remind people of the principles and ideas that Lumumba lived for and ultimately died: Self-sufficiency, self-determination, pan-Africanism, internationalism, and those principles obtain to this day, and they’ve been embraced by young Congolese in particular, young Africans in general, who are carrying out, building on the legacy of Lumumba.

So the cry is “Lumumba lives,” that is to say, his ideas, his principles. And I was in an exchange with one young Congolese before our commemoration yesterday, and he was sharing that there are a thousand Lumumbas in the Congo today.

So what we try to highlight is the extent to which the current generation has taken up the mantle, and is continuing that pursuit for a self-determined, independent Congo that is inextricably linked to the self-determination and independence of the African continent as a whole.

So that’s why we declare January 17 of each year Lumumba Day, and people go to LumumbaDay.org and they sign up to take action, either get a resolution passed commemorating the day; they can sign up to support the youth who are carrying on the tradition of Lumumba; they can be a part of the current movement in the Congo that is very much as critical today as it was during the time of Lumumba.

So it’s very current, very contemporary, and speaks to the tremendous importance that Congo carries, not only for Africa, but for the world as a whole, being part of the second-largest rainforest in the world, and is vital in the fight against the climate crisis.

And at the same time, Janine, being the storehouse of strategic minerals such as cobalt, which are vital in the pursuit of a renewable energy revolution.

So it’s at the nexus of critical resources that are vital to the future of the welfare of the planet as a whole.

JJ: I just wanted to ask you, if you have another minute in you, about precisely that, that Congo is not a story of the past. Congo is very much a story of the present. And I wonder, if journalists listening to this are looking to connect the history, and the ongoing history of exploitation, to the current exploitation, and are looking for stories as inroads to that, are there particular issues or stories that you would direct an enterprising U.S. reporter who’s looking to get into this; what should they start at?

Africa Report (5/17/21)

MC: Oh my goodness. There are so many. And if you’re talking about questions of peace and security, we see the instability unfolding in the Congo as a result of, in large part, U.S. foreign policy and financing and backing proxy leaders in neighboring countries. So peace and security questions.

Congo has suffered the deadliest conflict in the world since World War II. It’d be interesting to see a comparison between the response that we have in Ukraine in the media and what we see in the Congo, wherein as many as 6 million people have lost their lives. But yet the coverage seems to lack in comparison to how Ukraine is covered.

But if we’re talking about the Green New Deal and climate crisis and renewable energy revolution, you have to talk about Congo. There’s so many stories that you can address in that kind of pursuit: the minerals, cobalt, critical to renewable energy sector; the Congo Basin, which is the second-largest rainforest in the world, and yet it sequesters more carbon than the Amazon itself.

It is the largest repository of peatlands and tropical peatlands in the world, and stores enough carbon that it can address the carbon emissions of the United States for 20 years. So just a tremendous number of stories that can be addressed.

And then you have a situation where you have the Congolese, 70 million of them, living on less than $2 a day, while one billionaire, by the name of Dan Gertler, he makes $200,000 a day from royalties from Congo’s minerals. So the question of poverty, exploitation, plunder, that can be explored by journalists as well.

So there’s just a tremendous amount of stories that can be written around the Congo, because its significance, as I stated earlier, is not just for Africa alone, but for the world, and therefore, it demands the world’s attention, and it demands in-depth, nuanced treatment, not only of Congo itself, but of the Congolese people, and the enormous courage and dignity that they stand on in confronting the challenges that they face.

JJ: We’ve been speaking with Maurice Carney of Friends of the Congo; find their work online at FriendsOfTheCongo.org. Maurice Carney, thank you so much for joining us this week on CountersSpin.

MC: Thank you. Thank you, Janine. It’s my pleasure.