Siblings

by Brigitte Reimann

Penguin, £12.99

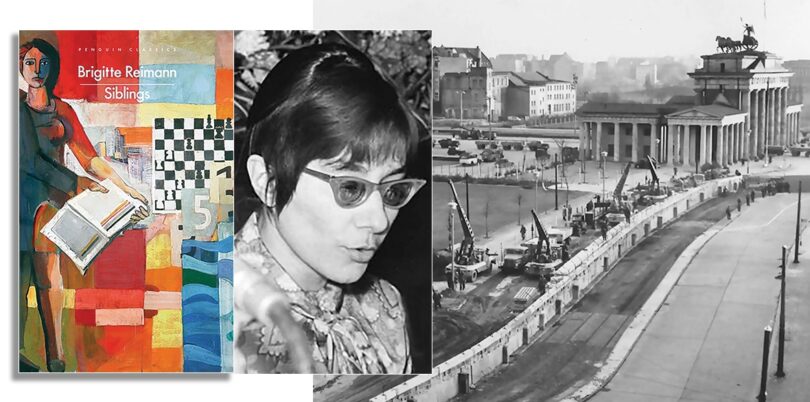

IN ITS series of classic international literature Penguin has recently published a novel by one of the most inspiring and talented writers of the GDR, Brigitte Reimann.

Siblings (first published in 1963 and here in an excellent translation by Lucy Jones) is set in Berlin in the 1950s and its vivid style, characteristic of Reimann, captures the atmosphere of the young GDR when it was attempting to create a new kind of society based on the ideals of socialism in the wake of the defeat of Nazi Germany.

This is the time when Berlin was divided between Eastern and Western sectors with no hard border but two different currencies.

At that time, around 40,000 people living in the East crossed to work in the Western sector every day.

This created an economic conflict and was a constant source of tension as many were attracted to live in the West because of more lucrative material opportunities and, at the same time, benefitted from the cheaper cost of living in the East.

The novel captures both the difficulties and opportunities offered during this period of building of a new society after the horrors of fascism.

Reimann depicts both the challenges and the excitement, such as the building of a completely new steel production plant in the middle of nowhere in which she gives us close-up portraits of the workers each of whom had different histories and experiences during the fascist period.

These people at first seem tight-lipped but gradually reveal the sensitivity and depth of character that pulses through the work teams.

The main character, Elizabeth, is an artist who also works in the steel plant. Why? This was the result of an initiative by the GDR government to bring workers and artists into closer contact: for artists to obtain better insights into the workplace and its demands, and for workers to come into contact with artists and an appreciation of their labour.

The novel centres around the close relationship Elizabeth and her younger brother Uli. Elizabeth feels passionate about the new state while her brother is increasingly disillusioned. It is this close relationship that gives the political arguments emotional colour.

Both have very different personal ambitions and a contrasting view of the futures and problems they face. Their older brother, Konrad, an engineer, had left the GDR for West Berlin because “he does not want his freedom to be limited.”

The younger siblings see this as a betrayal, not just of them as a family but of the new state. It causes a painful rupture within the family.

Elizabeth criticises Konrad, pointing out that his studies were paid for by the state and yet he now selfishly wants to use those qualifications to land a better-paid job in the West.

This was a huge problem in the GDR during the 1950s, when many academics and others with higher qualifications left the GDR in their thousands for a more comfortable life in the West at a time when the GDR urgently needed skilled labour, and this was one of the reasons the wall was built in 1961.

Elizabeth eventually breaks off contact with her older brother.

When Uli also suggests that he is thinking of leaving the country the tone of the novel changes into a spirited conversation and a playful, emotional reflection of the siblings’ childhood and their parents’ and grandparents’ lives.

The novel demonstrates the constant temptation and enormous pressure people were living through in the early days of the GDR and what makes it so effective is the way the stormy relationship between brother and sister gives an emotional dimension to the political problems of the day.