In a red-baiting New York Times review (2/14/23) of Malcolm Harris’ book Palo Alto, writer Gary Kamiya makes a false assertion about the persecution of Japanese people that amounts to denial of one of the most shameful chapters of US history. The Times should issue an immediate correction and apology.

A New York Times book review (2/14/23) gets an important fact about US history seriously wrong.

Complaining that “Harris doesn’t acknowledge the exceptions” to his “seamless, all-explanatory narrative” of California history, Kamiya writes:

Take his discussion of Japanese internment. As an example of how “embracing white supremacy and segregation meant sacrificing a certain amount of nonwhite talent”…he cites the story of the sculptor Ruth Asawa, who was interned along with her family and then “formally excluded from California” and thus forced to study out of state.

“At a time when the Bay Area’s artists began toying with Japanese ideas and forms, artists of Japanese heritage were banned from the state,” he writes, implying that all artists of Japanese heritage were banned from the state. This is not true.

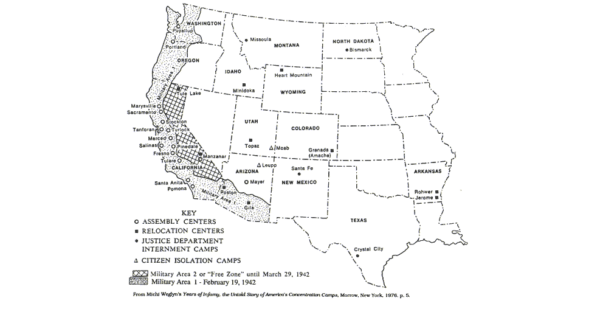

Contrary to Kamiya’s claim, it is true that not just all artists of Japanese descent, but all Japanese nationals and Japanese-American citizens were banned from California, beginning in March 1942. As Personal Justice Denied: Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians explained, under the US Army’s interpretation of President Franklin Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066,

all American citizens of Japanese descent were prohibited from living, working or traveling on the West Coast of the United States. The same prohibition applied to the generation of Japanese immigrants who, pursuant to federal law and despite long residence in the United States, were not permitted to become American citizens.

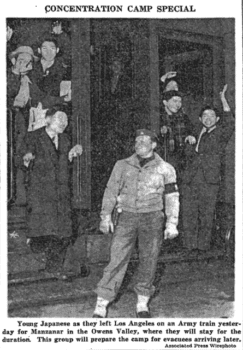

At the time, the New York Times (3/24/42) presented the incarceration of Japanese Americans in upbeat terms, describing people being rounded up into camps as “weary but gripped with the spirit of adventure over a new pioneering chapter in American history.” (See FAIR.org, 3/24/15.)

Japanese residents of some lightly populated areas of eastern California were initially not subjected to the ban, but the exclusion was extended to the entire state in June 1942. While the initial plan was to allow the people ethnically cleansed from the West Coast to relocate to other states, this was deemed impractical, and concentration camps, in the original sense of the term, were set up to confine them. As the commission report put it,

The evacuees were to be held in camps behind barbed wire and released only with government approval.

This is history that Kamiya, who writes a history column for the San Francisco Examiner, surely knows. So what does he offer in support of his assertion that Harris’ writing that “artists of Japanese heritage were banned from the state” was “not true”? This is Kamiya’s entire argument on the point:

To take just one example, the artist Chiura Obata, who was on indefinite leave from his professorship at Berkeley while interned at Topaz, was reinstated by the University of California president Robert Sproul in January 1945.

So the fact that a person released from a detention camp, after the War Department rescinded the ban on Japanese residents in California (effective January 2, 1945), was allowed to get his job back means that the ban didn’t really exist? This is a preposterous argument, and one that will surely mislead many readers about the scope of the anti-Japanese program.

Kamiya treats the fact that Japanese exclusion didn’t continue in perpetuity as a damning indictment of Harris’ book:

Palo Alto is chock-full of Asawas, and this ugly underside of California history should be told. But the book has virtually no Obatas, and that selection bias, clearly driven by Harris’s conviction that “positive” stories are simply window-dressing concealing capitalism’s dark reality, severely damages its credibility.

To the contrary: Kamiya’s insistence that the historical fact that all Japanese people were banned from California “is not true” severely damages the credibility of the New York Times. The paper needs to offer a correction, and an apology, immediately.

ACTION:

Please contact the New York Times to demand a retraction of and apology for the paper’s denial of the historical reality that people of Japanese descent were completely banned from California.

CONTACT:

Letters: [email protected]

Readers Center: Feedback

Twitter: @NYTimes

Please remember that respectful communication is the most effective. Feel free to leave a copy of your communication in the comments thread.