Former Mexican drug czar Genaro García Luna, the highest ranking Mexican official ever to be tried in the U.S., was found guilty in a Brooklyn federal court on Tuesday of drug trafficking and could spend the rest of his life in prison.[1]

García Luna took millions of dollars in bribes from the Sinaloa drug cartel, headed for years by Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán Loera, who was convicted and given a life sentence in 2019 by the same U.S. District Court Judge, Brian M. Cogan, who presided over García Luna’s case.

According to Mexican security analyst Alejandro Hope, “[García Luna] had a very close relationship for many years with U.S. intelligence. If he did what they say he did, that is a harsh sentence on all the verification mechanisms of U.S. intelligence.”

The Intercept reported that, when García Luna set up a security consulting company called GL & Associates Consulting, or GLAC, in 2012, José Rodriguez, the former CIA Station Chief in Mexico, was appointed to its board of directors.

A 31-year Agency veteran born in Puerto Rico, Rodriguez had been questioned by the FBI about his role in the Iran-Contra affair in the 1980s and in the 2000s ordered the destruction of CIA torture tapes, prompting The New York Times editorial board and Human Rights Watch to call for his prosecution “for conspiracy to torture as well as other crimes.”

Raúl Roldán, the FBI’s chief representative at the U.S. Embassy in Mexico when García Luna led Mexico’s national police, was also on the Board of Directors of GLAC Consulting.

García Luna won an award from the CIA, which thanked him for helping them.

Robert “Tosh” Plumlee, an 85-year-old former CIA pilot who wrote a book entitled I Ran Drugs for Uncle Sam about his exploits in the Contra War, said in an exclusive interview with CovertAction Magazine that he was told that “the CIA has a file on García Luna—amounting to over 5,000 documents, 15k-20k pages—that is classified. The CIA has that information classified at the highest. SAC Special Access Communication and to be read only at a designated SCIF: a ‘Secured Compartmentalized Information Facility.’ Some of those SCIF/SAC documents were found at Trump’s Mar-a-Lago compound.”

According to Plumlee, “if this does get investigated properly then it would be a bigger [scandal] than Watergate: Very Sensitive in all political circles.” Plumlee noted further that “the CIA has been working with corrupt Mexican officials and protecting the drug trade in Mexico since before García Luna came on the scene [late 1990s and 2000s]. Drugs go north and guns go south; there are contaminated people on our end, and dirty money from Mexico—drugs is a big and profitable business—that goes into campaign contributions and funds CIA operations.”

Poster Boy for the Failure of the War on Drugs

A devotee of a Mexican death cult which he allegedly worshipped at a secret altar in his government office, García Luna is a poster boy for the corruption and double standards associated with the War on Drugs.

In her closing argument, U.S. prosecutor Saritha Komatireddy said the Sinaloa cartel could not have built a “global cocaine empire” without García Luna’s aid, and that cartel leaders could live in “absurd luxury,” buying mansions, cars, gold and diamond guns, and keeping white tigers, black panthers and exotic wildlife as pets, because “nobody arrests anyone. That’s because the defendant was getting paid to protect them.”

A former Mexican intelligence operative born in a working-class neighborhood of Mexico City, García Luna in his official capacity spearheaded former President Felipe Calderón’s military-led crackdown on drug cartels launched in late 2006 when he was named Mexico’s public security secretary, a powerful cabinet-level position he held until 2012.

Enamored with U.S. spy movies and police shows, García Luna had first made a name for himself in the 1990s as a “spook fighting left-wing guerrillas [Zapatistas].”

From 2001 to 2006, he headed Mexico’s Federal Investigation Agency, or AFI, which according to testimony at the trial, provided Sinaloa cartel members in that time with its uniforms and equipment, and “cloned” police SUVs for them.

The Eastern District prosecutors have indicted two of García Luna’s closest former aides, Luis Cárdenas Palomino and Ramón Pequeño García, on corruption charges, while another former aide, Iván Reyes Arzate, who for years oversaw elite police units that worked with U.S. agents on sensitive investigations, has already pleaded guilty to U.S. corruption charges.

The case against García Luna was initiated after Jesús “El Rey” Zambada, a senior member of the Sinaloa cartel, testified at former Sinaloa kingpin Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán’s trial that García Luna had taken tens of millions of dollars in bribes from the the Sinaloa cartel.

Bribe money was used to pay off police, lawyers, judges and politicians to ensure their protection of the Sinaloa cartel and continued proliferation of the drug trade despite all the money invested in the War on Drugs.

Raúl Arellano Aguilera, a Mexican police officer who worked at the Mexico City International Airport, testified at García Luna’s trial that, when a certain code came over the radio, he and his fellow officers stood by as contraband went through Customs. “We couldn’t carry out searches, we couldn’t stop anyone, nothing.”

A top member of the Sinaloa cartel, Sergio Villarreal Barragán, testified on the first day of the trial that, when he intercepted a rival organization’s shipment of cocaine through the Mexican state of Chiapas, one of the cartel’s bosses showed up at a warehouse where the drugs were taken with García Luna, then in charge of the AFI, Mexico’s equivalent of the FBI.

An agreement had been reached whereby the cartel would take half of the profits from the sale of the two-ton load and García Luna would get the other half—or more than $14 million.

Villarreal Barragán told the jury that he was present several times when his boss, cartel leader Arturo Beltrán Leyva, gave bribes to García Luna, often at a safe house near a church in the southern section of Mexico City. The bribes, he said, typically amounted to $1 million or $1.5 million a month.[3]

According to Villarreal Barragán, much of the money came from a pool of funds assembled by Beltrán Leyva and other cartel leaders like El Chapo who was convicted at the same Brooklyn courthouse as García Luna in 2019.

Over time, Villarreal Barragán told the jury, the bribes financed the services of federal police officers who worked for García Luna and who helped the traffickers expand their operations through vast swaths of Mexico.

“The payments grew as the cartel grew,” Villarreal Barragán said, “and without that support it would have been practically impossible.”[4]

Torture and Sadism

The lone surviving member of a specialized unit against organized crime that operated under García Luna’s authority out of the state of Baja California in 2007 said that its mission was to “terminate the Arellano Félix brothers criminal organization and protect the Sinaloa cartel’s people,” and that members of the Arellano Félix gang were illegally detained and tortured using plastic bags at a safe house located on Lázaro Cárdenas Boulevard in the Hidalgo neighborhood.

According to the former organized crime officer, the men operating under García Luna were “masterly at torture, Salas Landaverde and De la Garza Herrada. De la Garza Herrada especially. He was a complete psychopath. I can tell you that because I saw him, he actually enjoyed torturing people with plastic bags and other horrible methods.”

Living Beyond His Means

According to a ProPublica report, shortly after García Luna’s arrest in Texas in 2019, Mexico’s financial intelligence unit (Unidad de Inteligencia Financiera, UIF) filed a complaint alleging that García Luna, along with associates Mauricio Samuel Weinberg López (Samuel Weinberg), Jonathan Alexis Weinberg Pinto (Jonathan Weinberg), and Natan Wancier, among others, created a network of front companies to move upwards of $50 million through bank accounts in 11 countries, according to Univision.

The Weinbergs have a business group dedicated to supplying Israeli security equipment and technology into Latin America, which suggests an intelligence connection.

As part of their effort to trace García Luna’s finances, the agents uncovered records in Panama that showed millions of dollars in suspicious transfers from offshore accounts into others that García Luna appeared to control in Miami, including one for a restaurant that appeared to be laundering the money. Through a front company, the Weinbergs had purportedly facilitated the purchase of a $3.3 million luxury house in Golden Beach, north of Miami, where García Luna was living prior to his arrest.[5]

Back when he was running the drug war in Mexico, a former U.S. Embassy official recalled being invited by García Luna to a party at what he described at the country home of his wife’s family in Cuernavaca, a weekend retreat south of the capital favored by wealthy Mexicans.

At one point, García Luna escorted some of his American guests to an immaculate, warehouse-like garage where he kept a gleaming array of restored vintage automobiles, one of them recalled. While difficult to estimate the value, the former official thought it might have been worth hundreds of thousands of dollars—perhaps as much as the home itself.[6]

DEA Notices García Luna Early On

The DEA noticed García Luna early on.

While still serving in the intelligence service, he and Cárdenas Palomino, his longtime lieutenant, arrived in Tijuana in the mid-1990s to offer to collaborate with U.S. agents working against the Arellano Félix gang, drug-running brothers who had been implicated in the 1993 murder of the Roman Catholic cardinal of Guadalajara.

“They gave a beautiful briefing,” one former DEA agent said of the two Mexican intelligence agents. “They had an operational plan, but it was all targeted to the Arellanos. When you talked about anybody else, they didn’t care.”

The former agent surmised that García Luna might already have been working for the Sinaloa Cartel, the Arellanos’ rivals, and said that García Luna and Cárdenas Palomino always pressed the DEA for information about the Arellanos.

In 2005, Reuters obtained a copy of an attorney general report, which found that nearly 1,500 of García Luna’s 7,000 agents in the new federal police force that he oversaw (AFI) were under investigation for corrupt practices. At the time the story was published, a group of AFI agents had just been arrested for kidnapping and murdering four alleged cartel hitmen. Several of the agents were said to be working for Guzmán’s Sinaloa organization.

“Go-to-Guy” for Failed Plan Mérida

In his opening statement, García Luna’s lawyer, César de Castro, pointed out that, throughout his long career, García Luna worked closely with a “who’s who of top U.S. officials in the State and Justice Departments, as well as in Congress and the White House.”

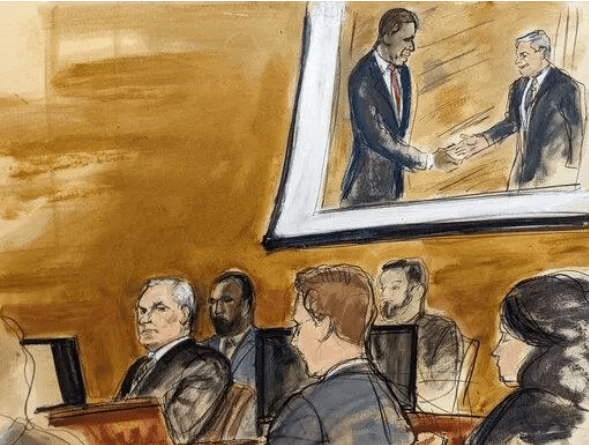

To that end, he showed the jury an array of photos of his client posing with Eric Holder, a former Attorney General, and Hillary Clinton, the one-time Secretary of State; and shaking hands with President Barack Obama.

These photos exemplify García Luna’s role as a key point man for Plan Mérida, a billion-dollar program lasting from 2008 to 2021 that was modeled after Plan Colombia—a militarized approach to the War on Drugs that provided a cover for fighting the left-wing Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC).[7]

John Feeley, a senior American diplomat who worked for years on Plan Mérida, stated explicitly that García Luna was “our go-to-guy” because he was supposedly “the most effective partner we had.”[8]

A 2008 profile of “Mexico’s top cop” in The New York Times Magazine reported that, with his “square jaw, squat build and crew cut,” García Luna was seen as “something of a wunderkind” during his early days in the intelligence services. Later on, he was described telling a group of police officers that he would never protect a criminal organization.

The Mérida goal of police reform ran into endless difficulties under García Luna’s leadership, however, because, when sensitive intelligence information was shared with Mexican police, even those trained and vetted by the DEA, it was leaked to the traffickers almost routinely.

American-trained police officials in those units were killed one after another, apparently betrayed to the traffickers by others inside the government.

One of the outstanding warrants for García Luna in Mexico centers on his role in Operation Fast and Furious (2009-2011), a sting operation in which the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) sold 2,500 guns and 10,000 rounds of ammunition to drug cartel operatives which could—in theory—then be tracked.

Mexico’s Federal Attorney General’s Office (FGR) said in a statement that “the weapons that Mexican authorities…allowed to illegally enter [Mexico under Operation Fast and Furious] have caused a large number of deaths and irreparable damage to justice.”

War Between Drug Traffickers

After the verdict was announced on Tuesday, Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador tweeted through his spokesperson that “justice has come” to a Calderón ally and that “the crimes committed against our people will never be forgotten.”

Previously, López Obrador had suggested that Washington investigate its own law enforcement and intelligence officials who worked with García Luna during Calderón’s administration, which López Óbrador referred to as a “narco-state.”

Of the 53,174 people detained under Calderón’s crackdown that was bolstered by Plan Mérida, only 941 belonged to García Luna’s favored Sinaloa cartel. Journalist Anabel Hernández wrote that “what Mexico experienced…[was] not a war on drug traffickers, but a war between drug traffickers,” with the [Mexican] government taking the side of Sinaloa.

The U.S. government appears to have been on the same side: In 2011, Jesús Vicente Zambada Niebla, the logistical coordinator of the Sinaola cartel, said that he was for years a U.S. government asset, and that he obtained weapons from the U.S. that were used to foment violence that could be blamed on the rival Beltrán-Leyva cartel, whom the U.S. government wanted to weaken and eliminate.[9]

World No Longer Worthy of the Word

In May 2011, a caravan of protesters led by poet Javier Sicilia, whose son Juan Francisco was murdered with six others by drug traffickers, marched from Cuernavaca to Ciudad Juárez chanting slogans like “We Have Had It” and “No More Blood.”

They denounced the War on Drugs as a principal factor underlying the violence that had left 39,724 dead since Calderón had taken over the presidency. Sicilia stated that, for him, with the death of his son, “the world is no longer worthy of the word. Poetry no longer exists in me.”[10]

It was men like García Luna who had made Sicilia and so many other victims feel this way, along with American foreign policy makers who had supported them. Together they had helped transform Mexico into what Charles Bowden characterized as the “global economy’s new killing field,” where violence, greed and cruelty was the norm.[11]

Notes:

- García Luna faces a minimum twenty year sentence. His sentencing is scheduled for June 27. García Luna also faces various Mexican arrest warrants and charges relating to government technology contracts, prison contracting and the bungled U.S. “Fast and Furious” investigation into suspicions that guns were illegally making their way from the U.S. to Mexican drug cartels.

- Barragán testified that he was present for a horrific execution where Beltran Leyva shredded two women with an AK-47 for insulting his wife, then ordered the bodies disappeared. Other testimony at the trial revealed the brutality of the drug trade: there was testimony about police officers being slaughtered and drug-world rivals being dismembered, skinned and dangled from bridges as cartel factions fought each other while buying police protection.

- Óscar Nava Valencia, known as “El Lobo,” described meetings at a car wash and a smuggler’s country house in which he paid García Luna millions of dollars for help that included U.S. government information about a huge cocaine shipment in Mexico. The payments were also intended to assure protection at a time when a schism in the Sinaloa cartel was heading toward a drug-world war. García Luna and a high-ranking police official “said they were going to stand with us,” Nava Valencia told jurors.

- In 2015, García Luna obtained his Master of Business Administration (MBA) degree from the University of Miami.

- García Luna didn’t testify at the trial, though his wife took the stand in an apparent effort to portray their assets in Mexico as legitimately acquired and upper-middle-class, but not lavish. ↑

- Jeremy Kuzmarov, Obama’s Unending Wars: Fronting the Foreign Policy of the Permanent Warfare State (Atlanta: Clarity Press, 2019), 297-301.

- With $11 million donated from the U.S., García Luna at one time helped create a TV show called The Team, which used U.S.-donated equipment in presenting Mexican government officials and police as heroes fighting the War on Drugs.

- The mysterious crash of a Gulfstream jet in September 2007 with four tons of cocaine outside Cancún in Mexico’s Yucatan region seemed to uncover a CIA drug-trafficking operation that would point to direct CIA support for the drug trade: a) the plane’s tail number was linked by European investigators to past CIA rendition operations (the plane flew at least three times to Guantánamo Bay); b) the plane’s co-owner, Greg Smith, worked as a pilot for CIA undercover operations in Colombia while the other co-owner, Clyde O’Connor, owned another jet used by CIA asset Baruch Vega in covert missions targeting narco-traffickers in Colombia; and c) the cocaine load on the jet was purchased through a syndicate of Colombian narco-traffickers that included a professed CIA asset named Nelson Urrego.

- Kuzmarov, Obama’s Unending Wars, 300.

- See Charles Bowden, Murder City: Ciudad Juárez and the Global Economy’s New Killing Fields (New York: Bold Type Books, 2010).